Uncertainty over how the Union Election Commission will regulate campaigning and voting to account for the pandemic is crippling the ability of parties and civil society groups to plan for the election.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

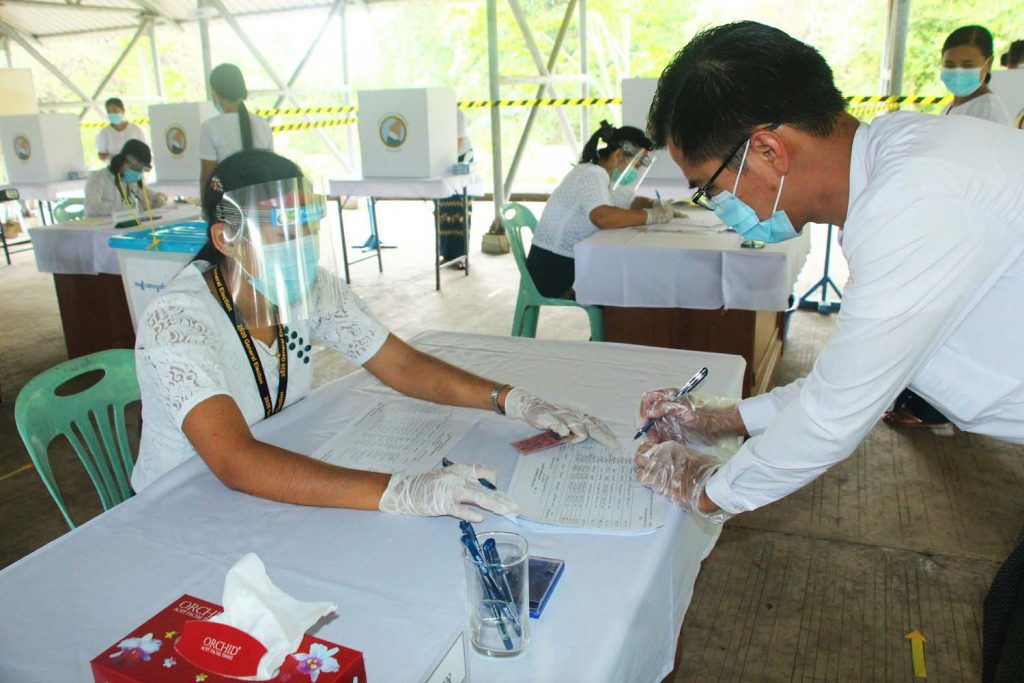

Under the shade of a metal car-parking shelter in the compound of the Union Election Commission in Nay Pyi Taw, women clad in matching uniforms and facemasks are corralled into an orderly queue by hazard tape, each standing about a metre apart.

At a desk at the head of the queue, each woman applies hand sanitiser and puts on plastic gloves before facing a temperature gun. This completed, they are handed mock ballot papers by a woman wearing a plastic visor.

The pretend voters mark the ballots behind screens a short walk away before depositing them in ballot boxes. UEC chairman U Hla Thein looks on from a steel chair, eyes creased in a smile above his facemask.

This demonstration of a socially distanced polling station on June 12, broadcast on MRTV and social media, aimed to show that elections could be held in November as planned despite the dangers posed by COVID-19.

Before Myanmar began responding to the pandemic, the UEC said there would be about 40,000 polling stations across the country, serving 37 million voters. UEC commissioner and spokesperson U Myint Naing told Frontier this number was only provisional and that the commission would consider dividing voters among a larger number of polling stations for safety. The June 12 demonstration was also provisional, he said, pending guidelines from the Ministry of Health and Sports.

However, there are more to elections than polling stations, and political parties and civil society groups are craving clarity over how campaigning and critical preparations such as the updating of voter lists will be allowed to proceed.

Large gatherings were banned in March as a health precaution and a more specific prohibition on assemblies of more than four people has been in place since April, making election campaign rallies illegal barring an exemption. The official campaign period begins 60 days before election day, but the UEC said that top government officials could begin campaigning early on July 1.

The uncertainty is crippling the ability of parties and civil society groups to plan for the election. There are also concerns about how any new rules to mitigate the continued risk of a COVID-19 outbreak will balance public health with the need to ensure both fair competition and the rights of voters.

Invest in Frontier Myanmar’s independent journalism by becoming a member. Sign up here.

The last few months have seen governments around the world grapple with – and, in some cases, exploit – this conundrum. Campaign rallies were banned in the run up to Singapore’s general election on July 10, which prompted parties to pivot to online events, and to field small numbers of volunteers for door-to-door campaigning while wearing facemasks and staying one metre apart from voters. Opposition parties said the ban on rallies robbed them of their main means of galvanising support, giving the ruling party an advantage.

In Malawi, health precautions were disregarded, to the chagrin of health officials, with the holding of mass rallies in advance of a presidential election on June 23. Malawi’s election was a repeat of one held last year, whose results were annulled by the African nation’s constitutional court because of evidence of fraud, and resulted in a widely celebrated transfer of power to the opposition. Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s indefinite postponement because of the pandemic of an election planned for this year has prompted criticism that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is failing to deliver promised democratic reforms.

In Myanmar, the holding of routine, credible elections is one of the main achievements of the transition from military rule. Postponing the election planned for November 8 would be hard to justify given COVID-19’s small footprint in Myanmar – with 321 cases at press time – but tight restrictions in the name of public health could still hurt the credibility of the poll.

Waiting for the ministry

An electoral code of conduct signed on June 26 by a majority of registered political parties – but boycotted by the opposition Union Solidarity and Development Party and several allied parties because of a last-minute disagreement over its contents – is largely based on the code used in the last general election in 2015 and contains no COVID-19 precautions.

At a meeting between the UEC and political parties in Yangon the day after the code of conduct was signed, Myint Naing said the commission was waiting for guidelines on safe campaigning from the health ministry and did not elaborate.

U Nay Win Naing, the director of civil society group Fifth Pillar, which focuses on voter education and encouraging youth and women to run for election, said greater clarity was needed now over all aspects of the election. He said groups such as his were eager to get a head start on voter education, but were reluctant to do so given the risk of sweeping changes to electoral rules and procedures to account for the pandemic.

The Fifth Pillar director said the election commission needed to carefully assess conventional aspects of the voting process, such as the inking of voters’ fingers to prevent them from voting twice, against the risk of infection, and broadcast their decisions soon.

However, Nay Win Naing added that clarity was the most important consideration in the introduction of any new rules. “None of us has experienced a situation like COVID-19 before and it means the way we all engage with this election will be different,” he said. “If the arrangements are too complicated, people may decide not to vote. We all need to think of different strategies to increase voter turnout.”

More on the 2020 election: An old controversy returns as govt gets the green light to campaign early

Turnout for the 2015 election was 69 percent in an electorate of 34.4 million. Although this rate is well above that of many mature democracies – 55.7pc of the United States’ voting age population took part in the country’s 2016 presidential election – two rounds of by-elections since 2015 in Myanmar drew turnouts of 37pc and 42pc respectively, and voter educators fear the pandemic will make attempts to revive interest for this year’s vote more difficult.

While the election commission claims that its hands are tied as it waits for directions from the health ministry, the ministry’s permanent secretary Dr Thar Tun Kyaw told Frontier that it was preparing to release election-related COVID-19 guidelines at the end of July.

Thar Tun Kyaw said the ministry would assist the election commission in keeping voters and polling staff safe from infection by forming election support teams at various administrative levels down to wards and village tracts.

He said these teams, which would include health officials and volunteers, would “check whether polling stations meet the guidelines” and ensure that voters are able to “wash their hands and observe social distancing”.

However, these duties are only relevant to election day and he was unable to indicate what measures would apply during the campaign period.

“I suppose we will have to continue with the existing orders, such as banning gatherings of more than [four] people,” he said. “The government might extend them to cover the campaign period, depending on the situation [regarding COVID-19].”

“These decisions are made by the COVID-19 central committee,” Thar Tun Kyaw said, referring to the apex body governing Myanmar’s response to the pandemic that is chaired by State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Connecting with voters

Parties are responding in varied ways to the uncertainty, with some simply content to wait and see. USDP spokesperson Dr Nandar Hla Myint said the party would like to campaign as it had in the past, but “we have not made many preparations yet for the campaign and are waiting to see what the UEC will say”. In 2015 the party held sizeable rallies in an attempt to compete with the NLD, alongside small-scale, door-to-door campaigning.

However, the ruling National League for Democracy is anticipating continued restrictions on gatherings and plans to focus more on door-to-door canvassing – which the party also engaged in heavily in 2015 – as well as investing more in online advertising, party leaders say.

Online campaigning and spending for all parties is likely to centre on Facebook, which accounts for the lion’s share of Myanmar’s online activity. Facebook use has quadrupled in the last five years, to about 22 million active users, making online campaigning attractive to parties regardless of the pandemic and social distancing rules.

Invest in Frontier Myanmar’s independent journalism by becoming a member. Sign up here.

NLD spokesperson Monywa Aung Shin said greater online spending, and the recruitment and provisioning of more volunteers to canvass neighbourhoods, could prove more expensive than holding rallies but said the party would be able to manage.

“COVID-19 is an unprecedented challenge that I believe we will overcome because of the strength of our party’s organisation, from the central executive committee to the ward and village tract level,” he said.

In contrast to the apparent nonchalance shown by the two largest parties, smaller parties are worried that restrictions would disadvantage them.

Daw Mya Nandar Thin from Yangon-based election monitoring group the New Myanmar Foundation says many parties lack the funding and knowledge required for digital campaigning, on which big or wealthy parties can afford to spend millions of kyat.

What is more, parties based in ethnic states tend to rely on a base of poor, rural voters that cannot be reached effectively online.

Kachin National Congress chair Dr M Kawn La said his party was weak in cities such as the Kachin State capital Myitkyina and will instead focus on rural areas. He said the UEC must allow, or make special arrangements, for them to engage rural voters directly.

“We need to go and meet people in the villages where we have our supporters. Now is the time to get closer to them,” he said. “We are stuck and don’t know what we can do.”

Voter lists, voter safety

Well before election day, voter lists must be corrected and updated, and civil society groups say this too requires a delicate balance between health precautions and inclusion.

Election sub-commissions in different townships compile voter lists based on information contained in the household member lists kept by ward and village tract administration offices, meaning most voters do not have to actively register.

However, this information is often incorrect or outdated, and fails to account for internal migration, so voter lists are publicly displayed at ward and village tract offices. Anyone who finds their name missing or details incorrectly logged can fill out a form requesting an amendment to the list.

The public display and correction process is expected in August, before campaigning starts in September.

Widespread errors in voter lists were one of the main sources of controversy in the run up to the 2015 election and fed suspicions of cheating by the UEC to advantage the then-ruling USDP. Accurate voter lists will be critical both to avoiding the disenfranchisement of voters and to strengthening the overall credibility of the election this year.

More on the 2020 election: Election commission berates opposition parties amid Aung San row

Mya Nandar Thin of the New Myanmar Foundation welcomed the UEC’s decision to display lists online, which would allow many voters to check their names and details without interacting with other people, but said that voter lists should still be physically displayed at the ward and village tract level for the sake of inclusion.

“There are citizens who are not familiar with digital technology, and areas where with bad internet connections or where the internet has been blacked out, such as in parts of Rakhine,” she said.

Mobile internet connections remain suspended in seven townships of Rakhine State and Paletwa Township in southern Chin State. The government ordered the ban in June last year in response to the conflict with the Arakan Army, prompting strong criticism from domestic and international human rights groups and the United Nations.

Mya Nandar Thin said that to avoid overcrowding at ward and village tract offices during the display period, the election commission should consider decentralising the process further by displaying voter lists on each street. She said this would require more volunteers to be recruited so that complaints and corrections can also be managed at the street level.

Commissioner Myint Naing said that in addition to the planned public display, the UEC was also proactively updating the voter list, for instance to include migrant workers who have recently returned from overseas because of the pandemic.

“We are trying to update the lists monthly, and also to delete the names of people who have died,” he said. “We are confident that voter lists will be accurate.”