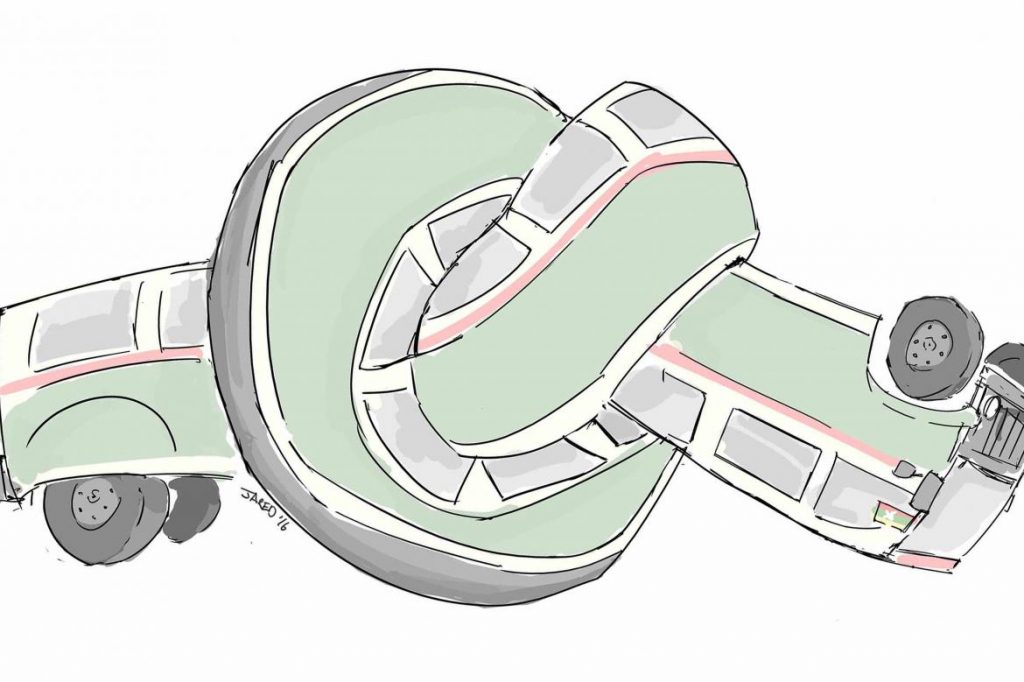

Many drivers in Myanmar still don’t seem to comprehend how easily carelessness can translate into tragedy.

IN 2015, more than 4,000 people died on Myanmar’s roads – an average of more than 10 deaths a day – in over 15,000 reported incidents.

Accidents can and do happen everywhere. But for anyone who has spent time travelling in the country – both inside and outside Yangon – it is obvious that the majority of incidents that occur here are easily avoidable.

Many drivers show an utter disregard for road rules, whether its drink driving, speeding or not wearing seatbelts (or helmets on motorbikes). They put not only the lives of themselves and their passengers at risk, but also other road users. As a result, road safety is now a major public health issue.

And it’s getting worse. The number of deaths per 100,000 people has more than tripled in Myanmar over the past decade. Last year it was ranked as having the second worst road safety record in the WHO’s Southeast Asia region, behind only Thailand.

Some action is being taken. The Myanmar Police Force has promised more resources to tackle the issue and punish drivers who flout the laws. Last week it was announced that drivers of vehicles that do not have seatbelts – including trucks and buses – will be fined and potentially jailed.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But these measures will make little difference until corruption is tackled. It’s no easy feat, but if drivers continue to wriggle out of sanction by paying a bribe to traffic police, then there will be little incentive to abide by the rules.

Myanmar does have a national speed limit: 30 miles per hour in urban areas and 50 mph outside cities (the Nay Pyi Taw highway, with a 60mph limit, being an exception).

It also has a drink-driving law and a motorcycle helmet enforcement law, but consistently ranks among the lowest in the region for enforcement. There are currently no laws in place regarding the wearing of seat belts, use of child restraints or the use of mobile phones while driving.

The condition of the country’s roads are also a major concern. The most notorious is the expressway that runs from Yangon to Mandalay via Nay Pyi Taw. Often referred to as “Death Highway”, the road saw more than 450 reported accidents in 2015 – almost double two years previously – and has been the scene of more than 400 deaths since 2013.

Drivers often lose attention on the 365-mile (600 kilometre) expressway. Other factors for its notoriety include poor maintenance, speeding and drink driving. Another major issue is the slow response time of emergency services on a road that has few services along it. Earlier this year, the government and WHO announced a program to cut the number of accidents and deaths on the road.

It’s an encouraging step, but few other major roads in the country get a similar level of attention. Most of these roads are poorly lit and maintained, and provide no hard shoulders for pedestrians, cyclists and motorbikes to share the roads with cars, buses and trucks.

This is one reason for the high ratio of pedestrians and motorcyclists in the country’s road safety statistics – according to Myanmar Police Force statistics in 2010, pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists accounted for almost 60 percent of all road deaths.

Myanmar has a small but committed group of people who are passionate about promoting road safety. But with few resources, any meaningful progress will require significant government support. Myanmar’s lack of spending on health has been well documented – particularly in comparison with defence – and road safety promotion is just one area where a shift in priorities is needed.

What is clear is that education programs should focus predominately on driver education. Because until recently only the elite could afford cars, most drivers are relatively new behind the wheel. Despite the appalling statistics, many still don’t seem to comprehend how easily carelessness can translate into tragedy.

This editorial was first published in the October 6 edition of Frontier.