An open letter to President U Win Myint has focused attention on discriminatory material in the government’s civics education curriculum for primary schools.

By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

LATE LAST YEAR, more than 120 civil society groups sent an open letter to President U Win Myint to urge a review of the curriculum for primary school civics classes that they say is promoting ethnic and religious discrimination.

The December 26 letter complained that the curriculum teaches children such phrases as “Thway hnaw dar nga doe mone, lumyo anyunt tone”, which translates as “We hate mixed blood, it will make a race extinct.”

The letter, copied to State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the Ministry of Education and the speakers of the national legislature, said that the civics education curriculum seemed to be an “attempt to indoctrinate the innocent minds of children with discriminatory practices”.

The letter expressed shock and frustration that the ministry designed the curriculum, which it said contradicted section 348 of the 2008 Constitution that prohibits discrimination on the grounds of race, birth, religion, official position, status, culture, sex and wealth.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But the letter did not clearly state what the discriminatory lessons were. Representatives from the some of the groups involved said it was based on evidence received from two parents.

One of the parents, Daw Aye Thein (not her real name) from Yangon Region, said that three of her children had learned discriminatory teachings in their civic education classes, at schools in Dagon Seikkan and South Okkalapa townships.

The daughter of a mixed Buddhist-Christian marriage, Aye Thein said she worried that such teachings would affect how her children viewed religions other than Buddhism, particularly in a broader context of rising Buddhist nationalist sentiment.

But she said favouritism towards Buddhism had been an issue since she was at school.

“I didn’t like having to pray in the morning at school because mostly it was Buddhist prayers so it excluded others,” she told Frontier.

Daw Khin May (name also changed) from Mandalay Region said she was shocked when she heard her daughter reciting a poem in late December that said children had a responsibility to “maintain the dignity of one’s own race” and avoid having one’s race “swallowed” by another. It also contained the line referenced in the letter to the president: “We hate mixed blood, it will make a race extinct.”

Khin May said the next day the poem was referenced in a question on the Grade 5 exam.

“I was shocked to see it on the exam,” she said.

She said the poem reflected the problems within the education system and was not the fault of the teachers. “Schools should not be for spreading hatred; they should be for spreading love. But it seems like nothing is going to change.”

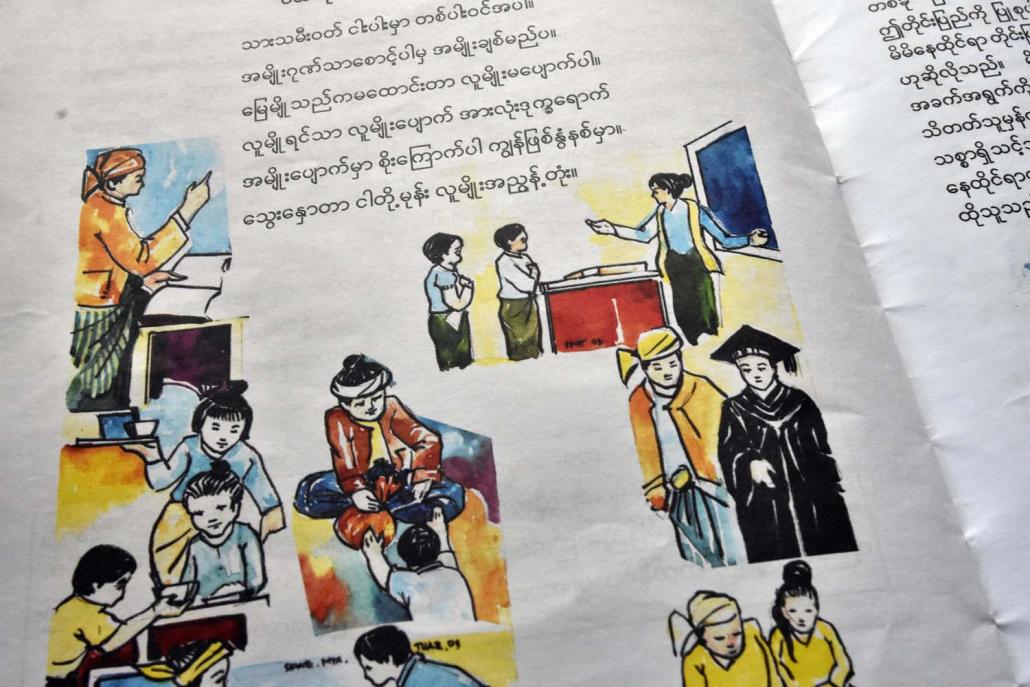

This poem in the teacher’s manual for a Grade 5 civics class contains the line, “We hate mixed blood, it will make our race extinct.” (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Competing claims

The 10 individuals who signed the letter included researcher and anti-hate speech campaigner Ma Zar Chi Oo, who told Frontier about a discovery that disturbed her while researching interfaith relations in five states and regions in August 2018.

Zar Chi Oo said she had found hateful, discriminatory language being taught to Grade 3 students while she was doing research at Meiktila in Mandalay Region, where communal violence in March 2013 left at least 43 dead, including 36 students and teachers at an Islamic boarding school. Arson attacks during the violence left about 12,000 people homeless.

She said the lesson being taught last year was similar to that which had appeared on the Grade 5 exam in Mandalay Region recently.

“I was shocked to see such lessons in Grade 3 students’ [exercise] books,” she said, adding that presenting such classes in a town where communal relations remained delicate risked aggravating the situation.

Zar Chi Oo said she began paying closer attention to civics classes after the incident and discovered that the discriminatory language she had heard was not in a student textbook but came from a guide for teachers, which they then read to the class. She suggested that this was deliberate, to make it harder to prove what was being taught to the children. Although she asked teachers from two schools to see the teaching guide, they said they were no longer using it and had been required to hand it in to the headmaster. Zar Chi Oo said the teachers were unsure whether the curriculum would be replaced.

“It is very dangerous to teach this to very young students,” she said.

When Frontier initially sought comment from Dr Zaw Lat Htun, deputy director general at the Department of Education Research, Planning and Training – the department responsible for developing the curriculum – he aggressively challenged the claims made in the open letter.

At a December 27 interview, he handed over two curriculum books for Grade 5 civics classes as evidence that the discriminatory language mentioned in the letter was not in the curriculum.

Zaw Lat Htun was also asked about the Grade 5 exam question from Mandalay Region in which students were asked to complete this sentence by filling in a word: Lumyo yin thar, lumyo pyauk, arlone dokka yauk (“If a race is swallowed by another race, all will be in trouble.”)

He declined to comment on the question, asking for evidence that it had in fact been asked.

He added that it was not his concern but a matter for the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population. This was an apparent reference to the Department of Immigration’s motto, which is similar to the exam question and is displayed in its offices: “The earth will not swallow a race to extinction, but another [race] will.”

Finding the evidence

At a monastic school in East Dagon Township, on the outskirts of Yangon, Frontier managed to get access to a Grade 5 teacher’s manual. Monastic schools are required to teach the state curriculum, and U Kawvida, the abbot of Thirimingalar monastery, who is responsible for managing the school, was happy to oblige.

The textbook contained the poem, titled Wunthanu seit dat (“Patriotic sentiment”), that was mentioned by Khin May, the parent who complained about the curriculum. The poem emphasizes the importance of loving one’s race, serving the country, being obedient to elders, and following the five precepts of Buddhism, among other things.

Kawvida said that he supported the inclusion of such teachings in the curriculum because he believes that everyone should be taught to love their own race. The teachings on race in the curriculum “are definitely true”, Kawvida said, but he also acknowledged that others might see the issue differently.

A class at the monastic school at Thirimingalar Monastery in East Dagon Township. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Daw Nyein Nyein, 68, has taught for about two decades at the monastic school at Thirimingalar monastery, which has nearly 200 needy students from throughout the country, some of whom are orphans.

She also defended the civics curriculum, which the school has been teaching since 2015.

“We don’t teach the students to hate others, but rather teach them to love their own race and marry their own people instead of marrying foreigners,” Nyein Nyein said.

For example, she said, women who married foreigners would encounter difficulties if the foreigner wanted to return to his country.

On January 11, Frontier returned to Zaw Lat Htun’s Kamaryut Township office with the evidence of discriminatory language in civics education teaching materials from the monastic school.

He said that since the first interview, more than two weeks earlier, the Ministry of Education had informed him about the controversial content in the teacher’s manual.

Asked why he was not aware of it earlier, he said that the copy of the teacher’s manual that he had shown at the previous interview was an old version, not the current edition adopted in 2015-16. Another reason he gave was that the book was printed before he was appointed to his current position.

“I came to realise [that the teachings were in the curriculum] when the Ministry of Education sent me a picture of the textbook,” he told Frontier.

Zaw Lat Htun said the education ministry had written to him on January 10 to ask that he discuss the issue with some of the key civil society groups that sent the open letter.

But the ministry had not specified whether it would remove the language from civics education, he said.

The material was probably included in the curriculum because of the situation in Myanmar after the communal violence that erupted in Rakhine State in 2012 and spread to other parts of the country the next year, he added.

“If it necessary to remove it from the lessons, according to the people’s willingness, then it should be done,” Zaw Lat Htun said.

Zar Chi Oo said on January 11 that the CSOs behind the open letter were ready to discuss their concerns but were yet to hear from the ministry.

“We welcome the acceptance to discuss this with us and are ready to help in any way,” she said.

Frontier tried unsuccessfully to contact the Ministry of Education for comment.

Human rights activist U Aung Myo Min said the promotion of discriminatory attitudes in schools was nothing new and was widespread.

He said such classes contradicted the constitution as well as the essence of education. Aung Myo Min said teachers had a key role to play and they needed proper guidance from the ministry.

“It is crucial that teachers have knowledge of peace and equality,” he said. “Otherwise, even if the curriculum is good, the teaching will still be bad.”