Myanmar’s Cholia Muslims have been celebrating a special and long-awaited anniversary that it hopes will raise its profile as it struggles to preserve its identity.

By KATRIN SCHREGENBERGER | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

MEMBERS OF Myanmar’s small Cholia community gathered in Yangon earlier this month to celebrate the 160th anniversary of their first mosque in the city.

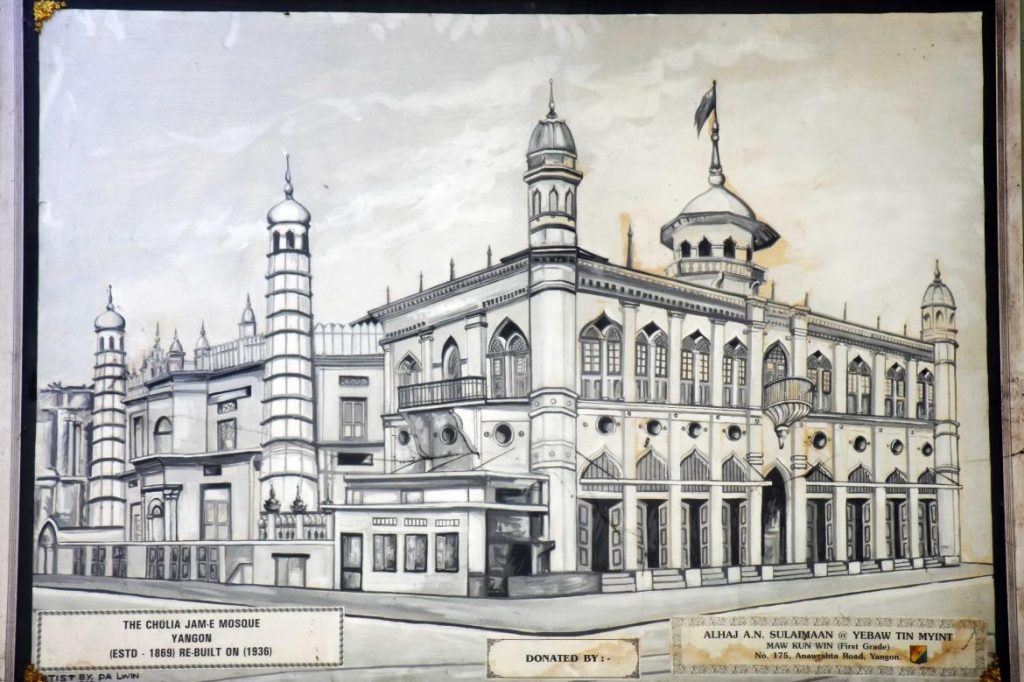

The Cholia – Tamil-speaking Muslims from Tamil Nadu in southern India – built a wooden mosque at the corner of Bo Sun Pat Street and Maha Bandoola Road in 1856. It was replaced in 1936 by the imposing Cholia Jamah Mosque, which today serves a community of about 100,000 people, most of whom live in Yangon. The Cholia Darga Mosque is nearby on 29th Street.

On February 4, about 200 people gathered at the Cholia Jamah Mosque for celebrations marking the anniversary.

NLD MP U Ba Myo Thein, centre, cuts a ribbon during a ceremony on February 4 to mark the 160th anniversary of the Cholia Jamah Mosque in Yangon. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The celebration could not be held on the date of the anniversary because it took the community two years to receive a permit for the event.

Most of those at the event were men and they included the Russian ambassador, Mr Nikolay Listopadov, and Amyotha Hluttaw MP U Ba Myo Thein (National League for Democracy, Yangon-5) who was standing in for Yangon Region Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein after he cancelled his attendance.

The anniversary celebrations were organised by the Cholia Mosque Trust, which was established in 1869 to manage the mosque, and financed by more than a dozen community organisations.

A photo of the exterior of the Cholia Jamah Mosque, one of Myanmar’s oldest, in downtown Yangon. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Speeches at the event outlined the history of the community, which traces its roots to the Chola dynasty, which was one of the most powerful in southern India and reached its peak from the late 9th to the early 13th centuries. The Cholia traded widely and their merchants were doing business in Burma long before the arrival of the British.

In 1856, Cholia merchants bought seven plots of land from the government on which the wooden mosque was built. A brick structure was erected on the site in 1872 and the mosque occupying the site today was erected in 1936 by an Armenian architect, AC Martin. Known in the Armenian community as Martirossian, he designed many of the grand buildings built in Rangoon during the colonial era, including the General Post Office on Strand Road, says the Architectural Guide Yangon, published in 2015.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

After the new mosque was built the trustees had a well dug on the premises because the water supply in the area was poor and it was shared with the nearby community when there were shortages.

During World War II, part of the mosque and adjoining buildings were badly damaged by Allied bombing raids that claimed several lives. In 1963, the trustees approved the removal of a dome minaret at the corner of the property so that the mosque could be expanded. It can hold up to 2,500 people during Friday prayers.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

As in most places of Islamic worship, only men may enter the mosque at prayer times. There are two halls in the mosque for special occasions, such as weddings.

During the colonial era, the Cholia community was granted permission to fire a gun kept in the mosque’s minaret to mark the breaking of the fast during the holy month of Ramadan. There was also a time when the Cholia were able to celebrate the birthday of the Prophet Mohammed at the Burma Athletic Association Grounds (now Bogyoke Aung San Stadium).

“Freedom of religion was very high under colonial rule,” said SS Khan, also known as U Min Oo, a member of the anniversary celebration committee. “Even if today all those privileges are gone, repression of the Cholia community in Yangon is not too bad because we are a very friendly community,” he told Frontier.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

The Cholia community had its own Tamil-speaking school until 1964, but shut it down to prevent the Ne Win dictatorship from nationalising the facility, as other private schools were after the 1962 coup d’etat.

The school’s closure was a setback for maintaining the community’s language and culture.

“The language was almost lost,” said Khan, adding that many younger generation Cholia cannot speak Tamil.

During the colonial era, the Cholia community was granted permission to fire a gun kept in the mosque’s minaret to mark the breaking of the fast during the holy month of Ramadan. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The role of language as the principal identifying characteristic of the community was recognised by the Supreme Court of Yangon in a 1936 ruling that the term “Cholia Muslim” denotes every Muslim whose mother tongue is Tamil, says the Yangon Architectural Guide.

The political reforms of recent years have created new opportunities for the community to celebrate their culture. During the school summer holidays in 2013, the Cholia community launched Tamil classes for young people and there are also plans to open a high school. The community also operates social welfare services, including an orphanage and workshops for people lacking professional skills.

Khan, 77, a third-generation Cholia, said his connection with Tamil Nadu was intact despite having no family left in India. Many Cholia left during the Japanese occupation and after independence in 1948 and the Ne Win coup d’etat in 1962, and Khan has travelled to India to visit friends who once lived in Myanmar.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

Other families have also maintained a connection with their ancestral homeland. “My parents sent me to India when I was 16,” said Cholia community member U Khin Maung Aye, 38. He lived in India for six years and his Tamil is fluent but returned to Yangon because it is home.

The Cholia Mosque Trust, which manages the mosque as well as the income from shops on the property, has been headed since 2001 by U Aung Thein, who is known in the community as SM Jamal Mohamed.

“The mosque is my first home; all the rest comes behind,” Aung Thein told Frontier. “If an air-conditioner is broken at home it can wait; but if the air-conditioning is broken at the mosque, I have to fix it right away.”

Steve Tickner | Frontier

On the mosque’s walls are two clocks he donated after returning from the haj, the pilgrimage to Mecca that all able-bodied Muslims who can afford it are required to perform at least once. Aung Thein helps organise pilgrimages for community members.

Al Haj U Aye Lwin, chief convenor of the Islamic Center of Myanmar, said Muslim communities in Myanmar still face many restrictions but should try to help others better understand the religion.

“There has not been a single mosque built in Myanmar since 1962; we should ask ourselves why,” he said.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

Teaching non-Muslims that attending prayers at a mosque is about purifying one’s heart would help to promote a more positive image.

“Mosques are not a threat,” he said.