After more than two years of uncertainty, the government has committed to establishing a National Land Law in line with the principles of the widely lauded National Land Use Policy.

By EVA HIRSCHI | FRONTIER

WHEN IT COMES to land, Myanmar suffers from a contradictory, fragmented and outdated legal framework. The country has more than 40 laws on the books – some of which date back to the colonial era – that are administered by a range of government departments and bodies.

The legal confusion, often coupled with limited or incorrect implementation, has had severe consequences – enabling, for example, a wave of land acquisitions by powerful companies, individuals and organisations that has resulted in the dispossession of vulnerable groups.

Even recently enacted legislation, such as the Vacant, Fallow, and Virgin Land Management Law and the Farmland Law from 2012, have been criticised for facilitating land grabs across the country.

Loud calls for reform – notably from civil society groups – have focused on the need for a National Land Law. At a recent forum in Nay Pyi Taw, the National League for Democracy government committed to drafting such an umbrella law for the sector.

Progressive policy

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The National Land Law will be based on the National Land Use Policy (NLUP) that was adopted by the former government in January 2016. The policy provides principles on how to implement, manage, and carry out land use and tenure rights in the country. While not legally binding, it is considered one of the most socially progressive policies in Myanmar, and includes the recognition of customary land rights, the inclusion of women in land governance and the acknowledgement of the rights of ethnic minority groups.

The NLUP is described as a “living document” that can be reviewed and updated as additional information is received or realities on the ground change over time. But since its adoption, the policy has been anything but alive.

The policy stipulates the creation of a National Land Use Council to coordinate the drafting of the National Land Law, but this body was only established in January – two years after the policy was introduced. Following its first meeting in April, the council arranged the first National Land Use Forum, which aimed to bring civil society organisations together with policymakers to exchange information and ideas.

Vice president underlines problems

Given this backdrop, the forum held in Nay Pyi Taw on October 2 and 3 was a milestone in land rights and policy making, marking the first step towards implementing the policy.

Vice President U Henry Van Thio, who also chairs the National Land Use Council, outlined the land governance problems Myanmar is facing, including ownership disputes, management difficulties, conflicting laws and corruption.

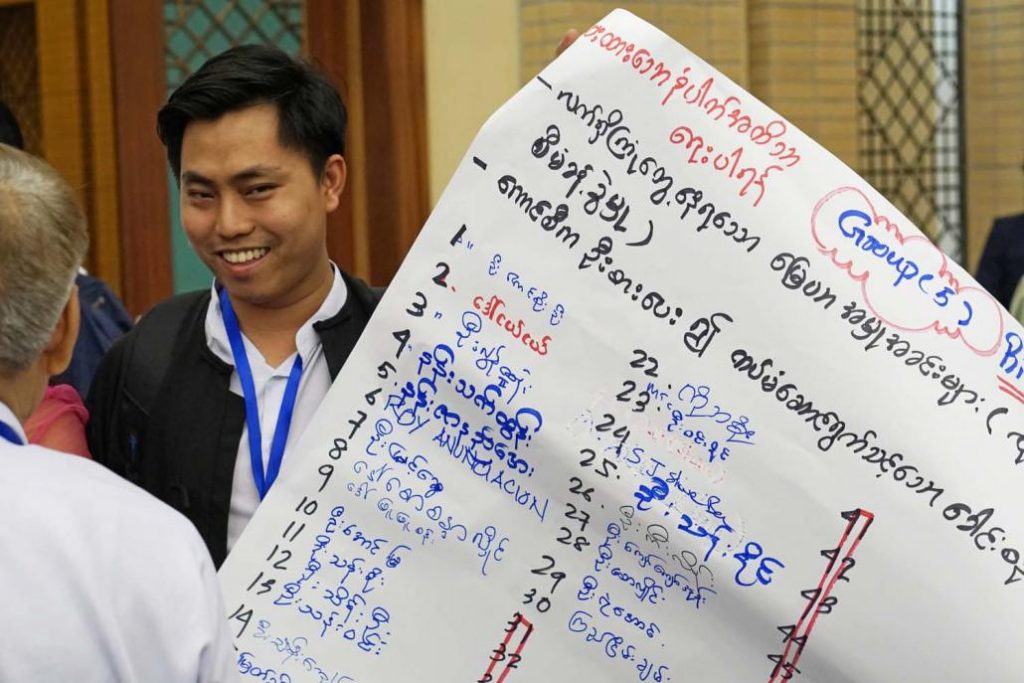

Attendees at the National Land Use Forum in Nay Pyi Taw take part in a group discussion. (Eva Hirschi | Frontier)

“All forum attendees are urged to discuss and make suggestions for the establishment of a good land administration and management system that could implement the aims, guidelines and basic principles of the National Land Use Policy,” the vice president said in his opening speech.

The forum was attended by a range of stakeholders, including ministers who are on the National Land Use Council, the Nay Pyi Taw Council chair, chief ministers of the states and regions, lawmakers, heads of departments, ethnic representatives, international organisations and civil society groups.

Eight panels were arranged to exchange information and encourage discussion, each followed by a question and answer session. Given the historic lack of dialogue over policymaking, it was noteworthy at the forum that all participants could ask questions freely and with no pre-approval process, and that directors of ministries took the questions seriously.

The topics of the panels were centred around the key principles of the NLUP, such as harmonisation of laws related to land administration, implementation of land use zones and information management systems. The Farmland Law and the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Management Law were examined, and a discussion held between the Promotion of Indigenous and Nature Together, the Kachin State Working Conservation Group and indigenous people from the Kamoethway area of Tanintharyi Region.

Much of the discussion focused on strengthening land tenure rights, reflecting the first “basic principle” in the NLUP: “To legally recognise and protect legitimate land tenure rights of people, as recognized by the local community, with particular attention to vulnerable groups such as smallholder farmers, the poor, ethnic nationalities and women.”

Examples discussed were the right to own property as an individual or joint titleholder, to divide property in case of divorce, and to recognise customary tenure and shifting cultivation.

Unclear drafting process

Union Attorney General’s Office deputy director general Dr Swe Swe Aung said his office had already prepared a draft of the National Land Law but was waiting to see what amendments are passed to other land laws before publicly presenting this draft. This statement created confusion – and some concern – because there has not yet been any consultation on the National Land Law with civil society organisations.

However, Swe Swe Aung was apparently referring to a “zero draft” created by the former government in 2015 – before the NLUP was even finalised. It remained unclear how or if the working committees would use the zero draft law in order to prepare the first draft for the national law. Forum participants recommended starting consultations at the pre-drafting stage, which the NLUC seemed receptive to.

An additional problem identified was the lack of statistics and accurate maps, as each ministry collects data for its own needs and there is little standardisation. Progress is slowly being made in this area. The forum received an update from OneMap Myanmar, a Government initiative which in 2015 began developing an online, open-access spatial data platform to make land data from various sources, both governmental and non-governmental, available to the public. This eight-year project also involves the Myanmar organisation Land Core Group and the University of Berne.

Praise and criticism

The panels, which provided up-to-date information but were heavy on theory, were followed by group discussions on the second day, which gave attendees more chance to interact, discuss and formulate recommendations. Some had gone to the event thinking it was a public consultation though and were disappointed that there was no joint formulation of recommendations.

“The forum serves as a starting point for a multi-stakeholder dialogue,” said U Shwe Thein, executive director of Land Core Group (LCG), a Myanmar civil society organisation working on land governance issues in Myanmar.

Shwe Thein, who was involved in organising the forum, said he was satisfied with the event and said it was just the beginning of a process of engagement around land issues.

Since political reforms began in 2011, Myanmar has seen an outpouring of land-related protests. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Some civil society representatives said they appreciated the possibility to participate in the discussions. “It was great that the biggest decision-makers such as director generals and representatives from different ministries were present – that was very unusual,” Ma Mai Thin Yu Mon from the Chin Human Rights Organisation told Frontier.

There was also criticism though. Several participants told Frontier they were disappointed that the forum focused mainly on presentations rather than discussions. “I appreciate the fact that the forum was open to the public,” said Ma Thyn Zar Oo from the Public Legal Aid Network (PLAN). “But I think they underestimated the capacity of civil society organisations who were attending the forum. We all work in fields related to land rights and land use, so we didn’t need basic information on land laws as presented by some panellists.”

“The forum was dominated by bureaucratic procedures,” said U Aung Kyaw Kyaw from the Magwe Regional Reinvestigation Committee. “It was actually more bureaucratic than democratic.” Asked how the event could have been made more democratic, he said, “The democratic principles should be reflected not only in the NLUP but also in the organisation of this forum. For example, the timeframe within which civil society organisations could apply for this forum was very short, only a few days, and it was not transparent how the participants were chosen.”

The online form for civil society organisations to apply to attend the forum was put online only a few days before the event took place. After being posted on the website and Facebook page of the Forest Department, it was spread widely by civil society groups, but some organisations likely heard about it too late.

Some civil society organisations also boycotted the forum, complaining that its objective was unclear, and the agenda and registration process were announced only at the last minute. “This forum intends to control people’s participation and it is found to be weak in transparency and accountability,” Land In Our Hands, a local NGO, said in a statement.

Nevertheless, the number of civil society applications was higher than organisers had expected. Out of 130 applications, more than 70 seats were granted – a significant increase from the initially intended 40 seats. It remains unclear how the participants were selected.

Long-term goals

The forum focused on the key structural challenges to land governance and seemingly demonstrated the government’s newfound commitment to implementing the National Land Use Policy in its entirety. This includes developing a National Land Law and ensuring harmonisation with other land-related laws.

Whether the forum was a success will only become clear over time – for example, when the National Land Use Council, which will next meet in November, begins drafting the National Land Law. Will the council use the discussions from the forum as input into the drafting process? It remains to be seen. Civil society organisations, for one, are hopeful that the forum is just the beginning of the process and there will be additional consultations as drafting gets underway.