After nearly five years of hosting hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees, Bangladesh has been implementing hostile policies in an apparent attempt to push them to leave. But with Myanmar in turmoil since the coup, repatriation looks increasingly risky.

By FRONTIER

When Chomar* fled from Myanmar to Bangladesh in 2017, she thought that she would be away from her home country for one, maybe two years. Nearly five years later, she has no idea when she will be able to return.

The 32-year-old Rohingya woman left northern Rakhine State in October 2017, shortly after the Myanmar military launched a series of clearance operations that the United States government has since recognised as genocide. At the time, Chomar was seven months pregnant and made the terrifying journey alone with her four-year-old daughter.

When she arrived in Cox’s Bazar nine days later, she found herself among hundreds of thousands of other Rohingya refugees all trying to find safety in a new and unfamiliar country. While they were first met with hospitality, Chomar feels that over time this support has turned into resentment.

“For the first two years, the [Bangladesh] authorities welcomed us and fed us, but later we started to become a burden for them. This is not our country and we know this, but for the authorities, we became a burden for them so they treat us like they dislike us,” Chomar, who runs a women’s empowerment network in the Kutupalong camp, told Frontier.

Since 2017, more than 750,000 Rohingya refugees have fled to southern Bangladesh in what has become the world’s largest refugee settlement. But as time drags on, with rising donor fatigue and limited progress on repatriation, circumstances in the camps have become progressively worse.

Bangladeshi authorities have become increasingly hostile to the refugee community, implementing anti-integration efforts and other policies that seem intended to make life untenable in Bangladesh and push the Rohingya back to Myanmar. But on the other side of the border, the very military that allegedly committed genocide against the Rohingya is now in power, after overthrowing the civilian government in 2021, raising serious concerns for their safety.

School closures and other crackdowns

While life in the camps has always been difficult, the conditions in recent months have been especially challenging.

“Immediately after the August 2017 atrocities, Bangladesh got a lot of international credit for not forcing the Rohingya immediately back to Myanmar. But since then, and particularly over the last six months or so, the restrictions that they’re imposing on the camps have really deteriorated,” said Ms Shayna Bauchner, a researcher in the Asia division of Human Rights Watch.

“They’ve been closing down schools, demolishing shops and setting up new movement restrictions and checkpoints and we’ve reported on increased abuses at the checkpoints with people being beaten and harassed by authorities.”

In December, Bangladeshi authorities began closing down private schools in the refugee camps, blocking tens of thousands of children from receiving an education. The directive, which is still in place today, specifically targets home-based and community-led schools that are run independently by the refugees.

Human Rights Watch reported that the closures intend to prevent the Rohingya from integrating into Bangladeshi society. While many in Myanmar see the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite living in Myanmar for generations, authorities in Bangladesh also view them as outsiders. The government directive ordered that all Rohingya schools must play the Myanmar national anthem and prohibited students from learning how to write and speak Bangla, the national language of Bangladesh, or even drawing the national flag of Bangladesh.

Bauchner noted that this decision will have consequences far beyond simply isolating the refugee population.

“It has a massive impact on children and their future ability to reintegrate into the community, whether that be in Myanmar or elsewhere. It’s very much sort of cutting off their futures and setting them up to be much less self-reliant than they could be,” Bauchner told Frontier.

Bangladesh’s commissioner for refugee relief and repatriation did not answer numerous requests for comment.

Since the private schools were closed, most students have had to rely on schools run by the United Nations and other recognised NGOs.

In November 2021, UNICEF and its partners launched the Myanmar Curriculum Pilot to “prepare the children for their return to Myanmar”. The curriculum is based on the national curriculum in Myanmar, but Cho Cho*, a 22-year-old Rohingya teacher who leads a women’s education initiative in the Kutupalong refugee camp, said that the curriculum falls well short of what children should be learning.

“In five years, the NGO schools only teach the alphabet, nothing more. The government thinks that by closing our private centres children will have to go there [NGO schools], but parents don’t want their children going to these MCP schools because they don’t provide a good education,” said Cho Cho.

Ro Zarni*, who previously taught at a private school in the Jamtoli camp, feels the same. His school used to teach around 200 students in grades six through 10 until it was also shut down six months ago following the same directive. He told Frontier that many of the NGO-run schools that follow the Myanmar curriculum have “unqualified teachers” and “only teach very basic things”.

When contacted by Frontier, UNICEF’s Representative to Bangladesh, Mr Sheldon Yett, did not address the criticism of the schools. Instead, he said that the MCP was “introduced following repeated requests from parents” and has received “positive feedback from parents and the wider Rohingya community.”

While Ro Zarni stopped teaching when the ban came into effect, Cho Cho has continued to secretly teach classes in the evenings. Along with 30 other volunteer teachers, they teach over 200 students between grades one and six with a focus on empowering girls.

But teaching comes with a risk. Cho Cho told Frontier that five Rohingya teachers in the refugee camps were recently detained because they continued teaching after the ban came into effect, and authorities demolished their shelters and learning centres. One remains in detention, while the other four were released after one month. Despite the dangers, Cho Cho is determined to continue teaching because it is “our right to teach the next generation of Rohingya children.” Frontier was not able to independently verify these events.

Beyond the school closures, the Bangladeshi government has also worsened restrictions on mobility in recent years, building barbed wire fences and blocking refugees from leaving the settlement or even going between camps.

“They want them [Rohingya] to live in a confined area. There’s a fear that they will spread out and the government does not want them to spread out into different places because it would be even more difficult to control them,” said Mr Bulbul Siddiqi, a professor at North South University in Dhaka. “It’s very clear from the government perspective that they do not want integration because that may delay repatriation further.”

In a further effort to contain the refugees, Bangladesh began sending some to Bhasan Char in late 2020, an isolated, flood-prone island in the Bay of Bengal. As of April, nearly 27,000 refugees had been relocated to the island, many of whom were involuntarily separated from their families and now have limited freedom of movement or employment opportunities.

The authorities also regularly shut down and destroy shops inside the refugee camps, claiming that they are “illegal.” In December and January, more than 4,000 shops were bulldozed as part of so-called clean-up operations, effectively wiping out income for thousands of refugees and their families.

Ro Zarni said that with all the crackdowns, the circumstances in the camps have started to resemble the conditions that Rohingya faced in Myanmar.

“In Myanmar, we needed permission to travel, and here in the refugee camp we have got the same situation. In Myanmar, we didn’t have the opportunities to do higher studies, and here in the refugee camps again we don’t have opportunities for education. In Myanmar, we didn’t have permission to have babies, and here there are [similar] messages from the government,” said Ro Zarni.

“I couldn’t say that it’s [the refugee camp] worse than in Myanmar but it’s similar.”

No progress on repatriation

Ro Zarni believes that the crackdowns intensified following the murder of Mohib Ullah, a prominent Rohingya leader whose death shook the community.

Mohib Ullah was killed in September 2021, with Bangladeshi police and his family blaming the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, an armed group active in the camps. Authorities have charged at least 29 Rohingya in relation to the murder.

But Ro Zarni said the Bangladeshi authorities have been acting like the entire Rohingya population is to blame.

“It’s like they think the whole Rohingya community killed Mohib Ullah. The government and the Bangladeshi people think we are all bad people,” he said.

Mohib Ullah was also said to be in favour of repatriation, something ARSA opposed.

Bauchner agreed that Mohib Ullah’s death may have led to some heightened security but believes that the crackdowns are more likely linked to exasperation on the part of the Bangladesh government, especially as repatriation efforts continue to be delayed.

“A lot of it comes back to this growing frustration and resentment toward the community and this feeling that they’ve been burdened with nearly a million Rohingya refugees and they’re not getting the international support that they would like,” said Bauchner.

Despite the massive needs, international funding has declined in recent years.

In 2022, the Rohingya Refugee Crisis Joint Response Plan, a UN-led effort through which most international funding is funnelled, set the total requirement at $881 million – down from the $943.1 million goal in 2021. But even with a lower objective, only $213.9 million – around 24 percent of the target – has been either committed or received as of July 2022. Every other year since 2018, the international community has committed over $600 million, representing a sharp drop-off for 2022, although nearly five months remain in the year.

The US government, one of the camp’s biggest donors, has similarly decreased its funding. From 2017-2020, it steadily gave more money every year, peaking at $313.8 million in 2020. That dropped to $298.6 million in 2021 and as of publishing, only $129 million so far this year.

Funding from countries like the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada has also decreased.

A spokesperson from the US State Department declined to comment on the drop in funding, but maintained that the US is the “largest single donor of humanitarian assistance” on the Rohingya refugee crisis and remains “committed to supporting this response”.

“When there is a lot of pressure for the international community to respond, there was a lot of funding. But as time goes on – the issue isn’t less critical – but there’s this donor fatigue and other issues that are happening elsewhere,” said Ms Yasmin Ullah, a prominent Rohingya human rights activist based in Canada.

She pointed to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which she said “basically took over all the attention” and became a funding priority for foreign governments and international organisations. Ullah said Western countries like Ukraine being prioritised over the plight of groups like the Rohingya is partially due to “racism and other systemic issues”.

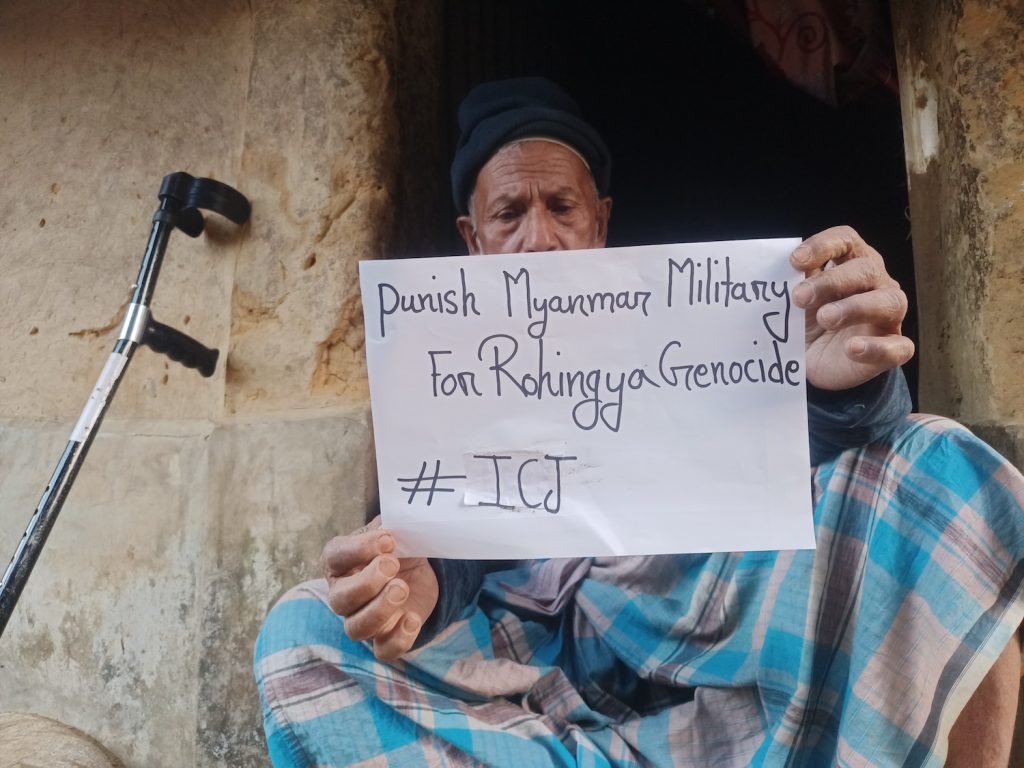

Ullah hopes that there might be more attention following a ruling by the International Court of Justice, agreeing to move forward with a case introduced by The Gambia accusing Myanmar of committing genocide against the Rohingya.

“This is just another step, but it’s a really huge step not only for a ruling but for other parties to do something meaningful and uplift the Rohingya community in the confines of the camps or wherever we are,” said Ullah.

“I hope that it can be a guiding principle for other actors and states to actually take a look at this and use it to ensure protection and assistance to the refugees.”

However, international court cases are slow-moving, and the initial media blitz tends to quickly fizzle out.

Since 2017, there have been repeated bilateral attempts between Bangladesh and Myanmar to kickstart repatriation, but each has failed. In 2018, over 2,000 Rohingya were set to return to Myanmar and in 2019 another 3,000 refugees were cleared to go home, but the Myanmar government refused to make changes that would ensure Rohingya’s rights were protected, and both repatriation efforts were called off.

Most Rohingya refugees in the Bangladesh camps want to return to Myanmar but refuse to go home until there is a guarantee that their rights will be protected and their citizenship, which is currently denied by the discriminatory 1982 Citizenship Law, will be recognised. The 2018-2020 war between the military and Arakan Army also made conditions unsafe for repatriation, and there are now fears that widespread fighting could resume in the state despite an informal ceasefire.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy came under intense criticism for defending the military’s operations against the Rohingya, and rolling out discriminatory policies like the National Verification Card process, which cemented Rohingya status as non-citizens.

With Aung San Suu Kyi now in prison, the parallel National Unity Government, appointed by a group of mostly NLD lawmakers, has struck a different tune. The NUG has pledged to recognise Rohingya citizenship and cooperate with international justice mechanisms.

But the military still sits in the capital of Nay Pyi Taw, and when Bangladesh resumed talks on repatriation in late January, they did so with the junta, not the NUG.

The military regime proposed beginning the return process with only 700 refugees, but even with such a small target, it has made no headway. Instead, Bangladesh is resorting to other tactics.

“The government of Bangladesh is not saying ‘go back to your country’ or forcing us physically,” said Chomar. “But the conditions made by the authorities tell us they want us to go back to our country, so indirectly they are forcing us to go back.”

Along with the crackdowns in the camps, Bangladesh is also trying its hand at more indirect methods of persuasion.

In June, thousands of Rohingya refugees staged a “Go Home” demonstration in the Kutupalong camps ahead of World Refugee Day. Cho Cho explained that while mass gatherings and protests are almost always banned in the camps, the authorities made an unusual exception for this campaign, likely because they supported its message.

Bangladesh also recently pushed this agenda during the drafting of a new UN resolution, which urged Myanmar to “immediately commence” the repatriation of Rohingya to Myanmar. Bauchner noted that the resolution is “dangerously out of touch” and “worrying” given that the conditions for a safe and sustainable return still don’t exist.

Cho Cho said “no one wants to live in the camps”, which she described as an “open jail”, but said now is not the time for repatriation. “The situation in Myanmar is very bad,” she said. “Where can we go? Who will be responsible for us?”

*Denotes use of pseudonym on request for safety reasons