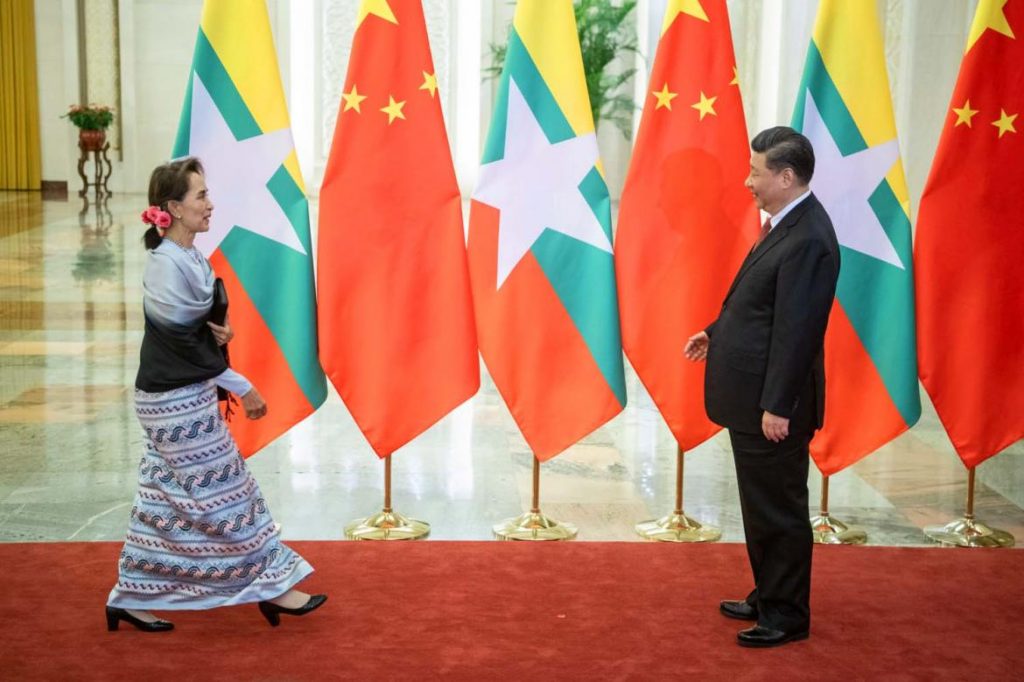

China acknowledged criticism of its Belt and Road Initiative at last month’s forum in Beijing, at which the Myitsone dam was off the agenda (at least publicly) at talks with Myanmar.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

WHEN THE Chinese embassy in Yangon posted a Xinhua article about State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s meeting with Chinese Premier Mr Li Keqiang to Facebook on April 26, the solitary comment below the post was, “How about Myitsone dam?”

It summed up the singular lens through which many in Myanmar have come to view bilateral relations over the past six months, and the growing concern that the Myanmar government, under pressure from China, might agree to proceed with the US$3.6 billion megadam in Kachin State, which was suspended in September 2011.

These concerns reached a crescendo on April 20 when hundreds of civil society leaders gathered at Yangon’s Novotel Hotel and announced a “one dollar campaign” aimed at collecting $1 from every citizen to raise funds to compensate China for scrapping the Myitsone Dam. They also addressed an open letter to Chinese President Xi Jinping saying that a dam on the Ayeyarwady River was unacceptable to the people of Myanmar.

This civil society event was held just four days before Aung San Suu Kyi left for the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, from April 25-27. The forum brought together dozens of world leaders to discuss Xi’s signature – and controversial – foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But when Aung San Suu Kyi returned from Beijing, the tone had clearly shifted. Media coverage trumpeted the 1 billion yuan ($148 million) grant that China had promised for economic and technical assistance. A Ministry of Foreign Affairs statement released on April 29 said this would be for “livelihood improvement, feasibility study for major projects and humanitarian assistance for the IDPs in northern part of Myanmar”. Three memoranda of understanding were also signed, but they appeared to cover broad areas of cooperation rather than individual projects.

Instead of Myitsone or the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone in Rakhine State, the state counsellor’s meeting with Xi focused on other issues of importance to the bilateral relationship, such as import quotas on rice, combating illegal border trade and human trafficking, supporting the peace process and defending Myanmar at the United Nations and other international fora.

So, what happened? Ma Khin Khin Kyaw Kyee, a lead researcher at the Institute for Strategy and Policy-Myanmar in Yangon who focuses on Myanmar-China relations, said most observers had expected that detailed discussions would be held on specific projects, including Myitsone, in bilateral meetings on the sidelines of the Belt and Road Forum.

In response to growing criticism of BRI, China wanted to use the forum as an opportunity to “show that BRI is mutually beneficial and to be implemented at the comfort level of the receiving countries”, she said. In the context of Myanmar, that meant avoiding any rhetoric on the need to proceed with Myitsone or other major infrastructure projects. Government spokesperson U Zaw Htay has said that Myitsone was not discussed in bilateral meetings.

“I think many observers in Myanmar are relieved that the agreements they reached do not seem to be binding,” Khin Khin Kyaw Kyee told Frontier. “But it is important to note that the detailed project discussions will take place with individual ministries, which can be much more low profile. Thus, we also need to keep our eyes on to the negotiation of these individual projects as well.”

Another close observer of China-Myanmar relations, U Maung Maung Soe, said the documents signed at the forum did not appear particularly significant.

“An MoU is not agreement … projects [contained in the MoU] can be cancelled if the [MoU] expires,” he said. “I think there were no agreements at the forum on things like Myitsone or Kyaukphyu. The two governments will need to continue discussions.”

He rejected the suggestion that the approach taken by the Chinese government at the forum was likely to herald a real shift in how it operates in Myanmar. “The Chinese government will never look out for the interests of the Myanmar people. They will work with the Myanmar government and military” to achieve what they want, he said.

It was precisely this type of assessment that Xi sought to address in his opening speech at the forum on April 26.

Launched in 2013, BRI in recent years has been dogged by accusations that it’s a debt trap of secretly negotiated bilateral deals that bring little benefit to the people of participating countries.

Xi said in his speech that China would in future “pursue open, green and clean cooperation” that delivered “true benefits” to ordinary people by combating poverty and creating jobs.

“We will adopt widely accepted rules and standards and encourage participating companies to follow general international rules and standards in project development, operation, procurement and tendering and bidding. The laws and regulations of participating countries should also be respected,” Xi said.

“Everything should be done in a transparent way, and we should have zero tolerance for corruption,” he said. “We also need to ensure the commercial and fiscal sustainability of all projects so that they will achieve the intended goals as planned.”

Mr James Crabtree, an associate professor of practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, said that the bad press for BRI in 2018 had caused some to wonder whether Xi would stand by the scheme. Last month’s forum though signalled it would be “full steam ahead”.

“China has invested a huge amount of capital [in BRI] and China thinks this project is working for it, and I think they’re right about that,” he said.

“I think China has also taken on board some of the criticism of BRI that occurred last year. The question now is, how is it going to make its programmes transparent in practice given how BRI tends to be organised, which is opaque and bilateral? It’s not really terribly obvious how they can do that.”

He said Myanmar was a “pure example” of many of the debates around BRI because of the type and scale of projects proposed, the country’s strategic importance to China and the “sheer unpopularity” of Chinese investment.

“I think it’s probably fair to say that the Myanmar government wants to keep a fairly low profile on what has become an unpopular issue. Therefore, in hindsight, it’s not surprising that they didn’t make any major announcements.”

Transparency would be important for the success of BRI projects, he added. “In the long run, these projects are going to be more sustainable if there’s more openness about what they involve, who the contractors are, and what the financial arrangements are.”

In Beijing last month there was also a different tone from Aung San Suu Kyi, who spoke of the importance of BRI projects being in line with amyotha simankein – Myanmar’s national plans – and the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan. In a speech at the forum, Aung San Suu Kyi also said that projects should “not only be economically feasible but also socially and environmentally responsible, and most importantly, the projects must win the confidence and support of local people”.

Although the state counsellor’s comments reflect a growing caution towards BRI, Khin Khin Kyaw Kyee said the Myanmar government was still committed to participating in the initiative – not just because of the potential economic benefits, but also to ensure China’s continued support in the peace process.

“Whether or not to be part of BRI is not a valid question anymore. We need to think about how we can best prepare to get the benefits and to minimise the risks,” she said. “In dealing with China’s BRI, we need to make sure that we have a master plan that is in line with a future vision for Myanmar.”

Inked in Beijing

Myanmar and China signed three bilateral agreements on the sidelines of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing.

- Agreement on Economic and Technical Cooperation. Includes a 1 billion yuan grant for socioeconomic development, including livelihood support, feasibility studies for major projects and support for internally displaced people.

- Memorandum of Understanding on China-Myanmar Economic Corridor Cooperation Plan (2019-2030). Will promote cooperation in industry, transportation, energy, agriculture, “digital silk road”, finance, tourism, environmental protection, people-to-people exchanges, science and technology and more.

- Memorandum of Understanding on the Formulation of the Five-year Development Program for Economic and Trade Cooperation. Aims to enhance cooperation in investment and productivity, no further details given.