The Southeast Asian bloc is considering stronger measures against the Myanmar military but a range of factors may preserve the unproductive status quo.

By FRONTIER

For the first time in its history, a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations has openly called for the regional bloc to consider suspending another member.

More than 18 months since the Myanmar military seized power and brutally slaughtered hundreds of protesters, ASEAN has grown increasingly frustrated with the lack of progress on the Five Point Consensus – a non-binding agreement drafted nearly three months after the coup. While many countries have criticised the junta’s lack of effort in fulfilling the framework, Malaysia has gone a step further, floating the idea of suspending Myanmar.

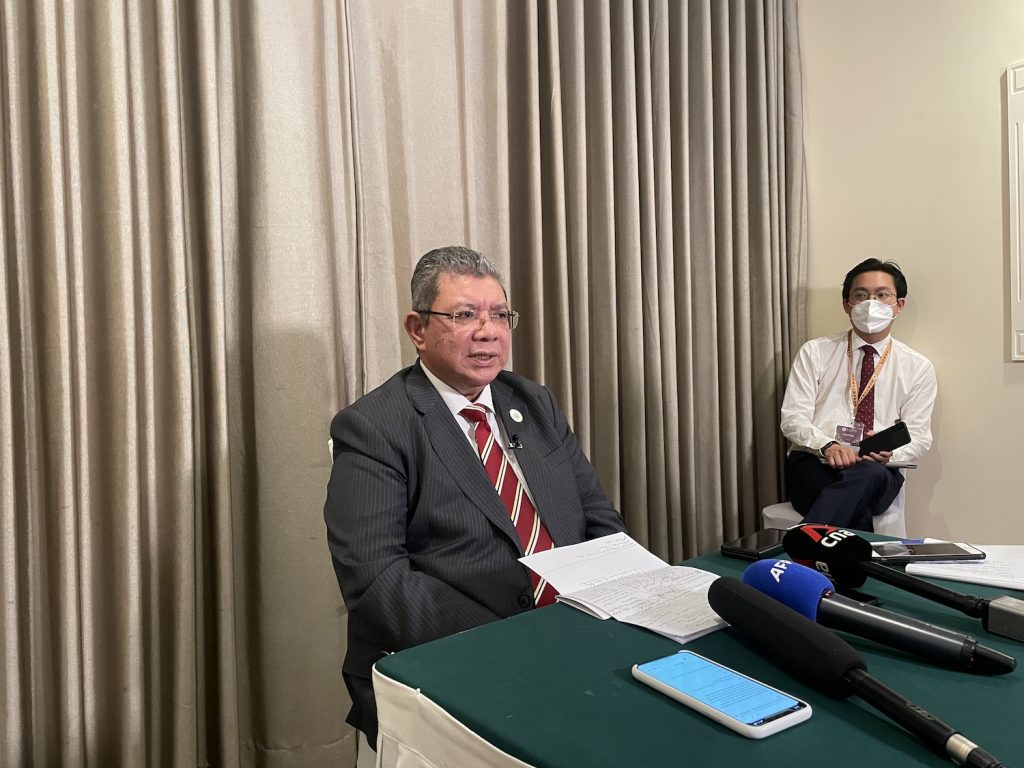

Malaysian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr Saifuddin Abdhullah told reporters including Frontier in August that the bloc will have to ask the “hard question” on suspension at the upcoming ASEAN Summit in November.

“We have to look at whether that [suspension] is something that is necessary but we are hoping that we won’t have to visit that kind of situation,” said the foreign minister.

However, experts are divided on whether ASEAN would actually take this unprecedented step and what it would look like in practice. Mr Charles Santiago, a Malaysian MP and the chairman of the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights, told Frontier that he “wouldn’t discount” suspension because the “level of anxiety and level of criticism against the junta is quite high”.

But others are not so sure. Ms Joanne Lin, a researcher at the ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said that suspension is unlikely because it would require the consensus of the entire bloc and some “might feel threatened by such a move” because of past and present crises in their own countries.

While the countries have yet to reach a consensus on how to move forward, most agree that the current approach has failed and are now looking to Indonesia as it prepares to assume chairmanship in the new year. But even a new chair will have to work within the confines of ASEAN and navigate the interests of each member state.

‘People are just pissed off’

The Five Point Consensus outlines five objectives aimed at resolving Myanmar’s political crisis – an immediate end to all violence, dialogue among all parties to the conflict, provision of humanitarian assistance, the appointment of a special envoy and a visit to Myanmar by the special envoy to meet with “all parties concerned”.

Coup leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing agreed to these points during a meeting with ASEAN leaders in Indonesia in April last year. However, he appeared to immediately walk back his commitments upon returning to Myanmar, saying implementing the plan depended on a return to “stability”.

Since then, the junta has continued to pursue its own goals without regard to the consensus. Besides slaughtering civilians, the regime has blocked ASEAN special envoys from meeting with deposed state counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and has allegedly co-opted humanitarian aid from the bloc, meaning assistance has failed to reach some of the country’s most vulnerable communities.

Consequently, there is a growing recognition in ASEAN that the Five Point Consensus is failing. In mid-September, Singaporean Minister for Foreign Affairs Mr Vivian Balakrishnan said the bloc is “deeply disappointed” by how little progress has been made, and called the junta’s “disregard” for the framework a marker of its “intransigence”.

Singapore officials have historically been some of the most outspoken members of the bloc when it comes to internal problems. Former Singapore prime minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew went as far as to tell United States State Department officials in 2007 that ASEAN should not have admitted Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos or Vietnam in the first place due to economic and social differences between these countries and the rest of the bloc. More recently, in 2019, Singapore’s former representative to the United Nations Mr Bilahari Kausikan said ASEAN should consider revoking the memberships of Cambodia and Laos due to foreign influence from China.

But this time Singapore is not alone. Along with Malaysia, Indonesian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ms Retno Marsudi has also expressed her frustration. A month before Balakrishnan’s comments, she said that rather than “goodwill” from Myanmar’s junta, the bloc has seen “many broken promises”.

A spokesperson for Indonesia’s foreign affairs ministry, Mr Teuku Faizasyah, told Frontier that Indonesia is “under the impression that many ASEAN countries also share similar unpleasantness” towards the Myanmar regime.

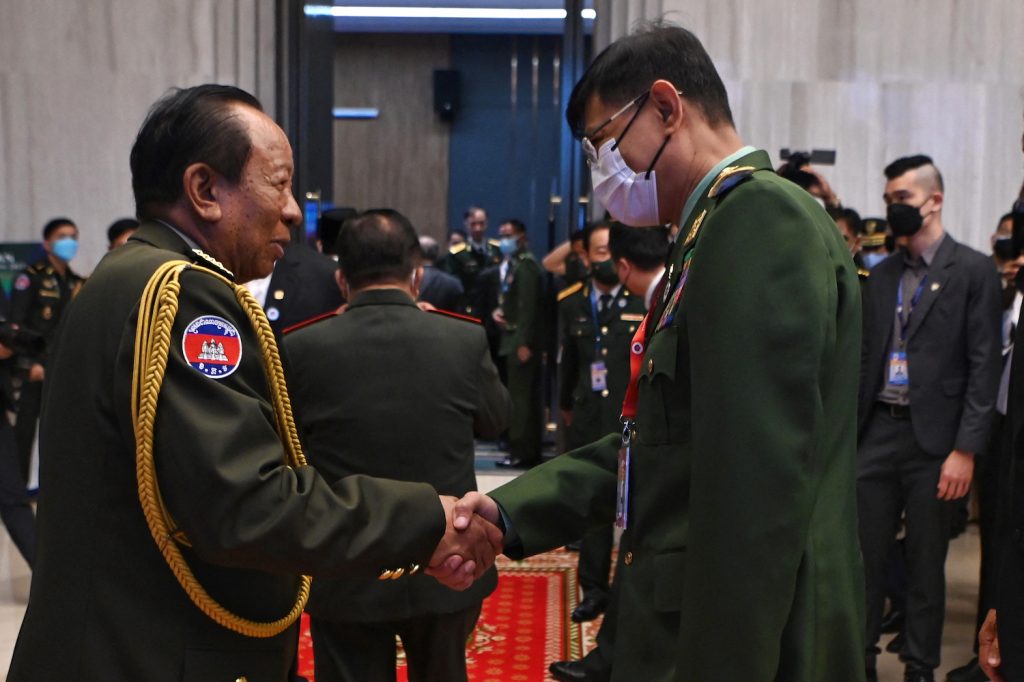

Even authoritarian Cambodia has changed its tone. When Cambodia assumed chairmanship in January this year, it pushed for more engagement with the junta; its ASEAN Special Envoy Prak Sokhonn even said the bloc had been “too hard on Myanmar”. But in June, after the regime threatened to execute four political activists, Cambodian Prime Minister Mr Hun Sen warned in a letter to Min Aung Hlaing that the act would “trigger [a] very strong and widespread negative reaction from the international community” and have a “devastating effect on ASEAN”.

When the military went through with the executions anyway, it signalled that it had no intention of making even the most minor concessions to ASEAN.

“The level of frustration has gotten to an all time high, even the Cambodians are frustrated against Min Aung Hlaing and the army – people are just pissed off,” said Santiago. “At one time, it was quite clear that Cambodia was siding with the military, but as things progressed, they have taken a different position. Even Hun Sen, who is no protector of democracy, came out and essentially said, ‘I’m tired of this.”

Among those who have criticised the regime, Malaysia has been the most vocal. Saifuddin is the only ASEAN representative to publicly acknowledge that he has met with members of the National Unity Government, a parallel administration appointed by elected lawmakers deposed by the coup. He held several meetings with NUG officials at the recent UN General Assembly in New York to “speak-up in solidarity with the people of Myanmar”.

Also at the UNGA, Saifuddin noted that between now and the November summit, ASEAN will need to review whether the Five Point Consensus is “still relevant” or whether it should “be replaced with something better”. These calls were echoed by Malaysian Prime Minister Mr Ismail Sabri Yaakob who said in his UNGA address that, in its current form, the “Five Point Consensus cannot continue any longer” and needs to be given a “new lease on life”.

The Malaysian foreign minister has also repeatedly called, without success, for the regime to be entirely excluded from ASEAN meetings. So far, only junta leader Min Aung Hlaing and his foreign minister U Wunna Maung Lwin have been blocked from ASEAN events, while lower-level officials continue to attend meetings.

Frontier asked Saifuddin during the August press conference why Malaysia has been so outspoken. He explained that the country has a higher stake in Myanmar’s stability because it hosts the largest number of Myanmar refugees in ASEAN. As of August, there are more than 159,000 Myanmar asylum seekers in Malaysia, 105,000 of which are Rohingya. Saifuddin, a former human rights activist, also described the Myanmar crisis as “a moral issue” and said that Malaysia “holds on dearly to the principles of human rights, freedoms and democracy”.

A cautious approach

Despite the widespread frustration, the bloc remains gridlocked on Myanmar, with no other country openly endorsing Saifuddin’s more aggressive proposals.

“The different political systems of all ASEAN member states means that not all countries will be equally invested in the restoration of democracy,” said Mr Evan Laksmana, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore.

Laksmana said that engaging with the NUG, for instance, could come back to bite certain regimes like the one in Cambodia, an effective one-party dictatorship that has jailed or exiled opposition politicians. Santiago similarly highlighted Thailand, whose military-backed government keeps tight control of the opposition.

Several ASEAN countries are also taking their cues from China. Along with Russia, it is one of the Myanmar regime’s biggest allies – blocking punitive measures at the UN Security Council – and remains an important economic partner and source of military equipment.

“The only thing that has stopped [ASEAN] from actually cutting [Myanmar] out is China,” said Santiago. “China is a big player here. China could play the role of peacekeeper, but its economic interest is stuck with the army.”

China’s influence is clear when it comes to close allies and fellow authoritarian states like Laos and Cambodia. But even the more democratic faction of the bloc often heeds the regional superpower.

Dr Chester Cabalza, the president and founder of the International Development and Security Cooperation in the Philippines, said Manila is playing a balancing act between the US and China.

The country’s former foreign minister Mr Teddy Locsin largely sided with Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore on the Myanmar crisis and was a staunch supporter of Aung San Suu Kyi. But an election in May brought Mr Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr, son of former Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr, to power, and it’s less clear where the new administration stands.

“If Marcos Jr chooses to bandwagon with China, then that would be a big problem. If China interferes and funds our infrastructure programs, then Marcos Jr will be tied up on the issue of human rights and that would affect our relationship with ASEAN and also with Myanmar,” said Cabalza.

But Cabalza said Marcos Jr may have a personal stake in pushing for human rights as he tries to reform his family’s reputation for corruption and human rights abuses.

“What Bongbong Marcos is trying to do right now is re-invent what he believes are misperceptions …. about the Marcoses. The people lived under martial law during the time of his father so he wants to bring back authority to the Marcos family,” said Cabalza. “This would be the best time for Marcos Jr to reinvent the wheel and discuss human rights, to mainstream the idea of human rights, not only in the Philippines but [in] Myanmar and ASEAN as a whole.”

But Cabalza cautioned that Myanmar may remain a low priority for the Philippines even under a new administration and, soon, a new ASEAN chair.

All eyes on Indonesia

In the early days after the coup, it seemed Indonesia, more so than Malaysia, would take the leading role in responding to the Myanmar crisis. Indonesia was among the most outspoken critics of the coup, Jakarta hosted the April 2021 emergency summit to establish the Five Point Consensus, and former Indonesian foreign minister Mr Hassan Wirajuda was an early frontrunner for the special envoy position.

But Indonesia gradually diverted its attention towards its chairmanship of the G20, which it assumed in January, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February.

Mr Tunggul Wicaksono, a researcher with the ASEAN Studies Center at the Universitas Gadjah Mada in Indonesia, said that ministers have been “focused on the G20 presidency rather than the ASEAN chairmanship” and there’s still “no indication that Indonesia has a specific framework for dealing with the Myanmar crisis.”

Laksmana also noted there has been less of a “personal presidential push” from Indonesian President Mr Joko Widodo to respond to Myanmar since the Russian invasion, with the president focusing his attention on Ukraine and even flying to Kyiv in June.

But despite Jakarta’s decreased engagement, there is widespread hope that an Indonesian chair will be tougher on the junta than Cambodia or Brunei. Wicaksono even speculated that Indonesia’s desire to be seen as a peacemaker and its efforts in Ukraine “could signal that Indonesia has a lot of ambition to take ASEAN to the next level as chair.”

Faizasyah, from Indonesia’s foreign affairs ministry, told Frontier that Indonesia’s more cautious approach has been deliberate.

“Our approach is not as much megaphone diplomacy, we try our best to affect change through many routes like bilateral and regional processes,” said Faizasyah. “There is sometimes a need to be open and vocal, but there are other times that we need to be more discrete in our approach.”

Wicaksono suspects that Indonesia will continue working within the parameters of the Five Point Consensus, choosing to “fix the approach rather than re-arranging” it. He said they would do this by focusing more on enforcement and accountability mechanisms, a tactic that sounds similar to what Malaysia has proposed multiple times over the last year.

Crucial to Indonesia’s tenure will be its ability to appoint the next ASEAN special envoy, who helps set the tone and direction of the bloc’s engagement with the junta. Although there has been talk of making the special envoy role an independent and long-term position, it currently rotates annually and has so far only been held by the chair’s foreign minister.

The chair also has the opportunity to invite guests to the sidelines of bloc meetings, as Cambodia did with Morocco and Azerbaijan at the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in July and August. However, guests do not have official roles in any ministerial meetings.

“They [the chair] can invite whoever they want as the guest of the chair, but it is not a blanket invitation to sit in meeting rooms with ASEAN,” Lin explained. “The guests of the chair are only invited to attend ceremonial activities like the opening ceremony. Any party to attend an ASEAN meeting has to be approved by all ASEAN member states – not just the chair.”

Indonesia could conceivably include the NUG in sideline meetings, or have its special envoy engage directly with the parallel administration. While Cambodia has shown little interest in working with the NUG, Lin said that Indonesia is likely to take a more “balanced” approach, which could include more inclusive outreach.

However, a source familiar with the situation, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the topic, said the NUG’s approach has put off some members of the bloc.

“The demands by the NUG to make engagement more public and even to the point of recognition, has made it so we’re all still holding back,” said the source, who confirmed that the Indonesian government has been communicating with the NUG, although “not exclusively and not always directly.”

The next big test is the summit in November, when Saifuddin expects ASEAN to consider whether or not to take the unprecedented step of temporarily reducing its membership from 10 to nine.

“Anything to do with suspension or membership is a very big thing within ASEAN,” said Lin. “It is really something that would disturb the charter. There are no written rules and no clause that says you can terminate or suspend anyone, so it’s going to be a political decision.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov had been a guest of the ASEAN chair Cambodia at the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in July and August. Lavrov was instead invited as a dialogue partner, which meant he attended some ministerial meetings at the event.