An investigation into the seizure of valuable farming land in Sittwe is likely to make uncomfortable reading for some politicians and public servants when it is tabled in the Rakhine assembly later this month.

By KYAW PHONE KYAW | FRONTIER

THE COMMUNAL strife that has dominated the news from Rakhine in recent months and years has ensured that most other issues in the state receive little attention.

That’s likely to change on January 23 when an investigation into a dispute over the ownership of valuable land in the state capital, Sittwe, is due to be discussed in the Rakhine Hluttaw – a dispute that involves 143 acres (about 58 hectares), 23 despairing farmers and some of the state’s most powerful politicians and public servants.

It is not difficult to understand why the land was coveted: It is near the centre of Sittwe but isolated from the rest of the city by a U-turn in the meandering Satyoekya Creek before it empties into the sea.

There is talk of a bridge that would provide easy access to the downtown area and eliminate the need for a circuitous 45-minute drive. It would also lead to a sharp rise in the value of the land.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The saga of dispossession and disrupted lives for the 23 ethnic Rakhine farmers at the centre of the dispute began in 1993 when government officials told them the land was no longer theirs.

In the absence of any official eviction documents the farmers said they were confused about what they had been told. There were also communication challenges. The farmers are ethnic Rakhine and can understand Myanmar but have trouble speaking it, which made their conversations with civil servants, who are mostly ethnic Bamar, difficult.

_dsf0133-6.jpg

U Kyaw Maung, centre, Ko Hla Tun Maung, right, and another dispossessed farmer stand in front of their former fields, now fenced for residential and commercial use, in the Rakhine State capital Sittwe. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

They continued farming the land until the early 2000s, when they said it was fenced by the authorities without any notice. The farmers said they did not receive any compensation but were too frightened to complain.

“At that time we didn’t dare to even listen to the BBC if we were told not to do it; we were very scared and didn’t discuss what happened with others,” said one of the farmers, U Kyaw Maung, 56.

He was told in the 2000s that his land had been confiscated, but was able to continue farming the site until it was fenced off in 2011.

After the land was taken, Kyaw Maung found employment as a carpenter. His plight worsened after he hurt his back in an accident and had to stop work. He pulled his seven children out of school and sent them to work as casual labourers to support the family.

In 2012, emboldened by the change in the political atmosphere, Kyaw Maung and the other farmers considered raising the dispute with politicians. They changed their minds after Rakhine was wracked by communal violence that year because they knew the conflict would be the focus of politicians’ attention.

The farmers’ hopes for the return of the land rest on being able to use old land tax receipts, which they showed to Frontier, as proof of ownership.

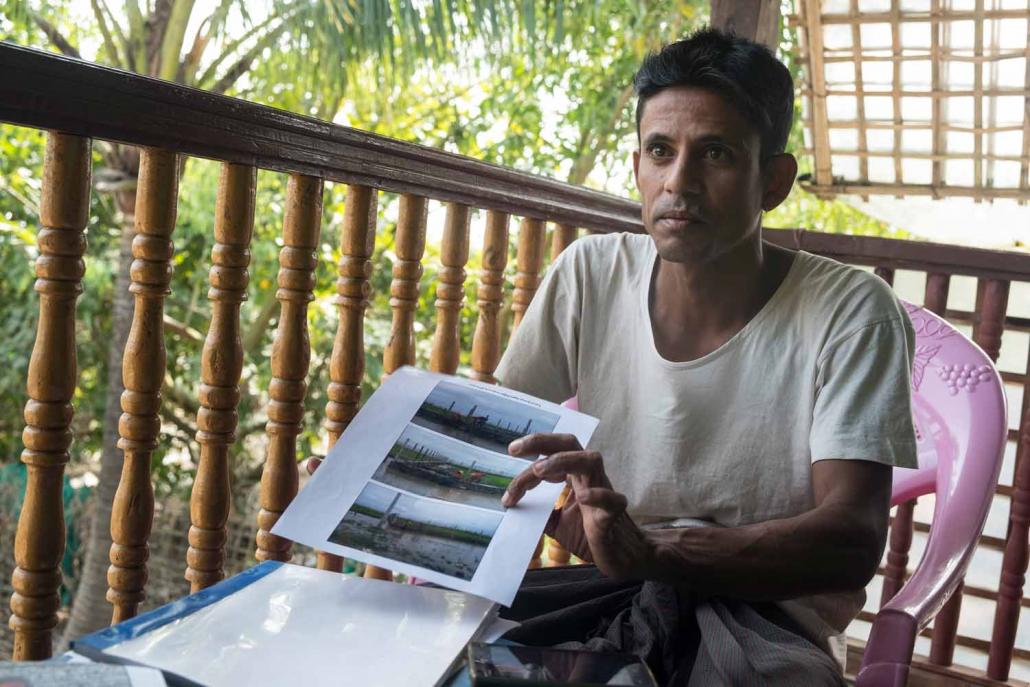

_dsf0117-2.jpg

Ko Hla Tun Maung holds a piece of paper with photos showing his land being fenced off during an interview with Frontier at his home in Sittwe on December 20. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

The National League for Democracy’s landslide election victory in 2015 and its subsequent appointment of a Rakhine, U Nyi Pu, as the state’s chief minister, gave the farmers renewed courage to campaign for the return of the land. They were eventually able to meet Nyi Pu in August. They said the chief minister was sympathetic to their plight and visited the site.

Encouraged by the chief minister’s response they drafted a letter explaining their situation and gave it to an Arakan National Party MP U Aye Thein, who represents Sittwe-1 in the Rakhine assembly and had shown interest in their case.

Aye Thein tabled the farmers’ letter in the assembly in September and was appointed to head an investigation commission into the alleged land grab, the MP told Frontier in an interview at his Sittwe home.

Aye Thein said the investigation found that 59 people were involved in the alleged seizure of the farmers’ land, including former state government ministers and high-ranking bureaucrats, military officers and businesspeople in Rakhine.

Uncomfortably for the ANP, the Rakhine Hluttaw speaker, U San Kyaw Hla, is among those who were involved, together with his deputy, U Phoe Min.

San Kyaw Hla told Frontier he had only discovered he was among the 59 after the land was allegedly confiscated.

“We were given the land during the term of the Union Solidarity and Development Party government but I am yet to apply for the ownership documents,” he said in a telephone interview from his Sittwe home.

000_hkg10222188.jpg

An Arakan National Party rally in Yangon in October 2015. Several senior members of the party received portions of the confiscated land from the previous Union Solidarity and Development Party government. (AFP)

San Kyaw Hla said he had “heard” that a retired military officer been involved in applying for the land and fencing it but declined to give the individual’s name.

“Actually, I don’t know who is the mastermind of the case yet; I really don’t know who gave me the land,” he said, adding that this was why he had supported the appointment of the investigation commission by the hluttaw.

“Even though I don’t know the result of the investigation commission, in my opinion the farmers should get their land back,” San Kyaw Hla said

But while San Kyaw Hla said he supported the formation of the commission, he has not gone so far as to cooperate with its investigation.

Aye Thein said San Kyaw Hla and Phoe Min had both declined to be questioned by the investigation commission, despite repeated requests.

The land, which is valued at about K70 million (US$52,000) an acre, has been fenced and is being subdivided into plots for housing or commercial use.

“When we saw that our land had been fenced we felt very sad,” said Kyaw Maung.

“I could not stand it anymore so I went to the Settlements and Land Records Department office with our tax receipts for the land. But a women officer threw my tax papers away and said, ‘You wont get your land back; don’t you ever return to this office’. I can’t talk back to her. When I returned home, tears were falling from my eyes,” he said.

U Yan Myo Aung, 62, who had farmed eight acres of the disputed land, said he had been forced to beg to have enough food to eat.

“We are facing difficulties and we hope the NLD can solve them,” he told Frontier.

Ko Hla Tun Maung, 35, said the 2.87 acres he had farmed in the bend of the Satyoekya Creek was under the name of his ailing mother, Daw Hla Kyaw Oo, who is in her 80s.

He is not optimistic that the land will be returned. Neither is Aye Thein.

“I don’t think the farmers will get their land back, but I will try to ensure they are compensated,” the MP said.

Aye Thein said he would be able to reveal the names of all those involved in the alleged land grab after investigation commission’s report is tabled.

“After January 23, I will tell the public,” he said.

The state’s minister for Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry and Mining, U Kyaw Lwin, discussed the case in an interview with the Rakhine Gazette last October.

Kyaw Lwin said he had been quite surprised when he discovered that those alleged to have confiscated the land were “the people who shout their love and support for the Rakhine people”.

Since its establishment, the ANP has cast itself as a party representing ethnic Rakhine interests against unfair treatment from Nay Pyi Taw and the majority Bamar. For its members to be implicated in a land grab together with members of the military-backed USDP is deeply embarrassing and could potentially harm the party’s image in the state.

ANP general secretary U Tun Aung Kyaw, a lawmaker in the Pyithu Hluttaw, confirmed that the speaker, deputy speaker and several other party members had accepted land at the same site from the former regional government.

“Some ANP lawmakers who are ministers in the USDP government also got land. These people are party members in name only; they rarely even came to the party office once they got their minister positions,” he said.

He offered only qualified support for San Kyaw Hla and Phoe Min.

“It is their personal affairs and not related with ANP,” he said. “We won’t say anything unless it harms the interests of the Rakhine people.”