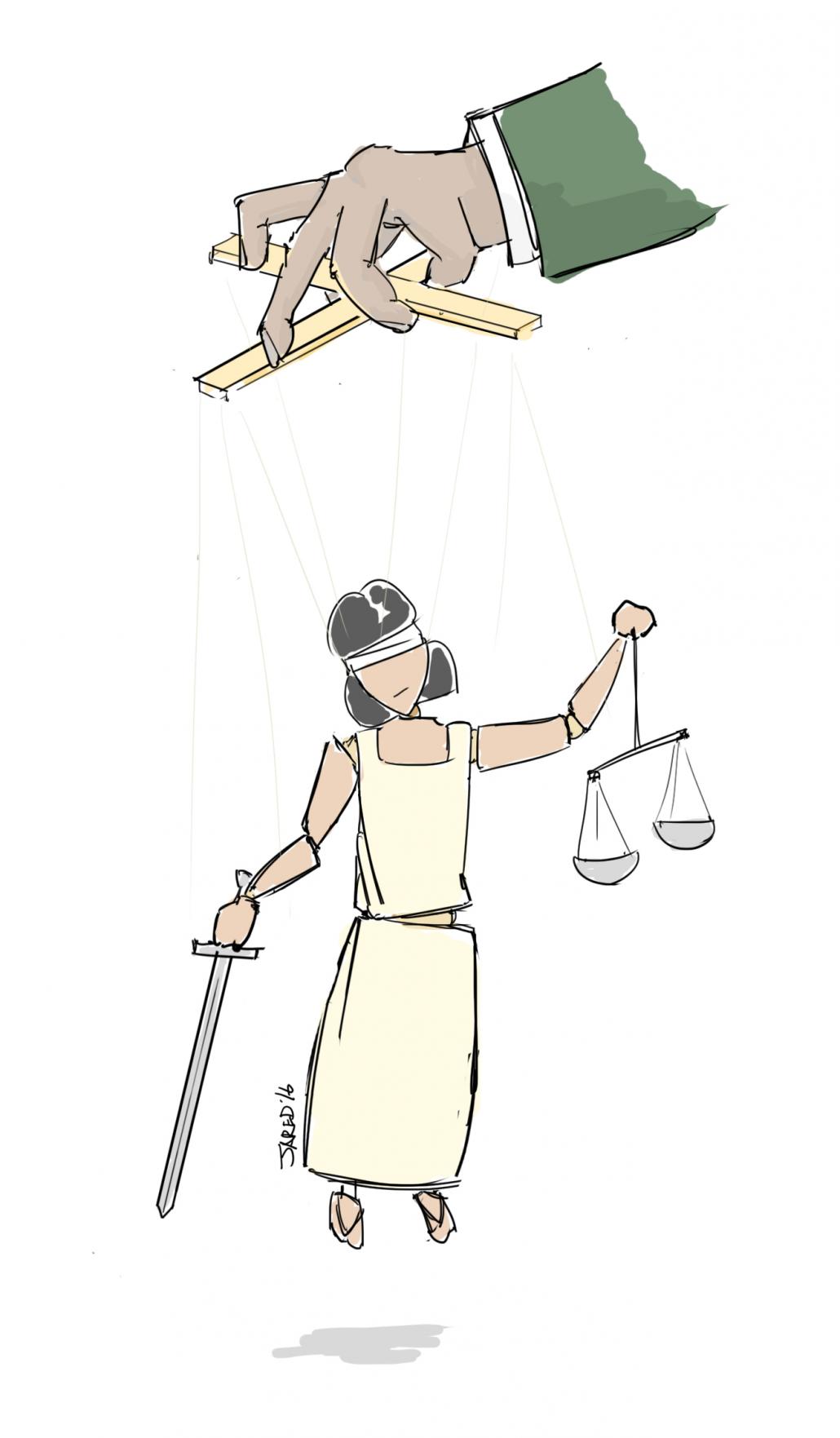

Government interference and corruption have left Myanmar’s legal fraternity in a shambles, its lawyers poorly trained and its judges cowed by police.

It’s a tale with a familiar ring. Six decades ago, Myanmar’s legal profession was arguably the strongest in the region. Its fraternity of judges and lawyers could hold their own with those in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Decades of government interference and corruption have left it a shell of its former self. Under military rule, the judiciary became a tool to implement and sustain policies enacted by the army, and maintain “law and order” by keeping dissidents in check – if not in prison.

Judges have been cowed by both the police, who brought criminal cases to court, and the General Administration Department. This is unlikely to change any time soon: These bodies are under the Ministry of Home Affairs, which in Myanmar’s new quasi-civilian system remains firmly in the grip of the military.

In politicised cases, the result is often a foregone conclusion, making the trial simply for show. For this reason it’s not uncommon for judges to exit the courtroom in the middle of proceedings – leaving lawyers to argue at an empty bench – or simply fall asleep.

Jared Downing / Frontier

The legal profession long ago stopped attracting the best and brightest minds, who were instead drawn to subjects like medicine or engineering. There are, of course, some notable exceptions, but they are just that – exceptions.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

There was a moment after the trial of BBC Burmese reporter Ko Nay Myo Lin on June 6 that crystalised the challenges the new administration will face in reforming and uplifting the judicial sector.

Accused of assaulting a police officer during a protest in Mandalay last March, Nay Myo Lin was found guilty and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment. He plans to appeal the conviction.

Speaking to reporters afterward, the judge reportedly defended the decision by saying he wanted to protect civil servants, and that a different verdict would have made police officers fearful of carrying out their duties.

Regardless of whether Nay Myo Lin should have been found guilty based on the evidence presented, this comment suggests an analytical failing on the part of the judge.

It also indicates that there has been little change in the mindset of those tasked with upholding the law.

This is not surprising. It is instilled in judges from day one, when they begin their training, which is conducted like a military drill camp. Every morning they have marching practice. Until recently they were also taught how to use firearms. Lessons are delivered rote, in a classroom. Like the rest of the education system, reasoning and critical thinking are not encouraged. This is a fundamental problem, arguably more significant than that of corruption.

But of all the challenges the government faces –managing the economy, improving health and education, and balancing relations with the military, to name a few – raising the standards of the judiciary is given less prominence than it should.

Perhaps it is the scale of the task, which is daunting. In its annual Rule of Law Index, the World Justice Project last year rated Myanmar 91 out of 102 countries surveyed.

There are no quick fixes. It will require a thoughtful, long-term strategy, and the political will to implement it. This will inevitably lead to conflict with vested interests, those who benefit from the status quo.

But there is some reason for hope. For many years, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has made rule of law a mantra, if not a priority. The new government is said to be working on a long-term strategy for reform, although has not released any details to the public. Donors understand the importance of the sector and there appears a willingness to put funds behind a viable plan for change.

Small steps are being made. In recent years, lawyers barred for political reasons have been able to regain their licences. They have also been able to form new associations to better represent their interests and lobby the government and legislature on important issues.

In terms of training, the undergraduate law curriculum has been overhauled. Five “rule of law” centres that have been set up with donor assistance have trained hundreds of lawyers.

More scrutiny is being placed on judges and their decision-making, including by the media. In Mandalay Region, the government has even reportedly formed teams to monitor the proceedings in court and the performance of judges.

Much more will be needed. And given how integral rule of law and standards in the legal profession are to all facets of the reform process – from encouraging investment to raising standards for law drafting – the government cannot afford to fail.

This editorial originally appeared in Frontier #51, published on June 16.