The return of conflict-displaced families to a Kachin State village, managed by the Tatmadaw without the input of the Kachin Independence Organisation, has deepened mistrust between the two sides of the conflict and may have endangered lives.

By YE MON | FRONTIER

Photos HKUN LAT

EIGHT YEARS after conflict in northern Myanmar resumed between the Tatmadaw and Kachin Independence Army, the Myanmar government and military have begun initiatives to return or resettle some of the more than 100,000 people displaced by the fighting.

These activities, which include a national strategy for the closure of camps for internally displaced persons, or IDPs, have taken place in parallel to renewed peace negotiations with the Kachin Independence Organisation, the KIA’s political wing, aimed at securing a bilateral ceasefire.

The government and the Kachin Humanitarian Concern Committee – a body that includes Kachin humanitarian and religious leaders, as well as two members of the KIO’s IDP committee – have also discussed potential cooperation on the resettlement process.

After informal talks in February, the National Reconciliation and Peace Centre and KHCC met in Nay Pyi Taw in April to discuss the safe and dignified return and resettlement of IDPs, expanding humanitarian assistance to IDPs and pathways to closing the IDP camps.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The inability of the KIO and the Tatmadaw to reach a bilateral ceasefire agreement has limited progress.

The exception is one village in Waingmaw Township, where the Tatmadaw has overseen the return of around 200 people from camps in Myitkyina, Waingmaw and Bhamo townships.

In January 2019 the Tatmadaw escorted 17 families back to Nam San Yang village and a second round of returns took place in March. The village, which is on the Myitkyina-Bhamo Highway, suffered heavy damage in fighting between the Tatmadaw and KIA. The area has been contaminated with landmines and is close to front lines.

Tatmadaw spokesperson Brigadier-General Zaw Min Tun told Frontier that the Nam San Yang return had been a success and the military planned to expand its IDP return activities in cooperation with the government.

Zaw Min Tun said the government had proposed returning IDPs to 12 villages and the military would assist with transportation and landmine clearance operations.

“We have already undertaken landmine clearance operations around Nam San Yang village,” he said.

A community displaced by conflict returns to the ruins of their former village of Nam San Yang. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

A success story?

Though the return of IDPs to Nam San Yang proceeded smoothly, it took place without the support or participation of the KIO and the influential Kachin Baptist Convention, and doubts have been raised about the long-term viability of the return and even the basic security of the returned families.

KBC chairman Reverend Hkalam Samson, who also chairs the KHCC, was scathing about the initiative, telling Frontier that the return to Nam San Yang had put IDPs’ safety at risk.

He said those who had returned were now struggling to get by because they were no longer receiving humanitarian support from aid groups, but had received little help from the government either.

“The international aid groups have stopped their support to them because the villagers are not IDPs any more. Also, there is no safety for either aid workers or the villagers,” he said.

Among those who returned to Nam San Yang was Daw Than Yi, a 51-year-old Buddhist who had fled to Bhamo.

She is staying with a friend in the village because her house was burned in the fighting and she doesn’t have the money to repair it. She said she was upset at the lack of support provided to returning IDPs and called on the government to do more to help them.

“No one is helping to repair our houses that were destroyed during the conflict,” she said. “They should at least have fixed our houses before we returned.”

IDP students who have returned to Nam San Yang village sleep inside a Catholic church where they are temporarily staying. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

She also expressed concern about safety, particularly the large number of land mines that remain in the area. The military only de-mined parts of village, she added.

“For example, only if I have the money to repair my house will the military check for mines around it,” she said.

Hkalam Samson said the KHCC and KIO plan to discuss the Nam San Yang issue with the NRPC and would urge it to conduct a review.

“If we review it carefully, then we will know if the return of IDPs to Nam San Yang village was successful or not.”

Return and resettlement activities would not be successful without cooperation between the military and KIA, Hkalam Samson added.

The International Committee of the Red Cross said it was not involved in the return activities and is not providing support to those who had gone back to Nam San Yang. The organisation also said it was worried about their safety.

“Landmines and explosive remnants of war could seriously impact the safety of people residing in the area, and the sustainability of their return,” it said in a statement to Frontier.

“The ICRC is ready to support sustainable solutions for IDPs, when the return process (or local integration or relocation) actually takes place according to the principles of voluntariness, safety and dignity.”

Others have pointed out the capacity of premature returns to undermine the prospects for peace and a genuinely sustainable returns process. In a briefing in May, the Brussels-based International Crisis Group said that while recent developments had created an opening for IDPs to go back to their homes, much would depend on the outcome of ceasefire talks between the Tatmadaw and KIO.

“Conditions are not yet conducive for large-scale returns in Kachin State, but in the short term it may be possible to identify resettlement opportunities away from conflict zones and to provide support to communities that receive IDPs,” the ICG said.

It also noted that the military-led activities had “sown mistrust and threatened to undermine prospects for progress”, and urged the government to take charge of the return and resettlement process and expand consultation with Kachin leaders.

The Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, which is leading the IDP camp closure strategy process, declined to answer most of Frontier’s questions about Nam San Yang. It said only that it was not providing assistance to those who had returned to the village, and that the NRPC planned to meet the KHCC later in July to discuss the issue.

The people of Hpare village who fled conflict in 2011 continue to live in a camp nine miles from the homes they left behind. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

Ceasefire first

KIO spokesperson Colonel Naw Bu told Frontier that the KIO wanted to sign a bilateral ceasefire before addressing IDP return and resettlement.

“We’ve already said this to the government and military,” he said. “Unless there is a ceasefire, we will not cooperate with them on this issue.”

On Nam San Yang, Naw Bu said the government and military had undertaken the IDP returns unilaterally, without consulting the KIO.

He said that after the villagers returned to Nam San Yang, the Tatmadaw asked the KIA to pull back one of its front-line outposts in the area. When it complied, the military then established its own checkpoint on the site, Naw Bu said.

“They should not have established it. The people will be concerned about it,” he said.

Zaw Min Tun would not confirm that the military had established a new checkpoint near Nam San Yang or that it had instructed the KIA to shift its outpost.

The return to Nam San Yang has created risks of a split in the KHCC along religious lines.

Those who returned were mostly Roman Catholics. The main Baptist organisations did not participate and most displaced Baptist residents of Nam San Yang remain in IDP camps.

The KBC said it did not prevent Baptists from returning to Nam San Yang and those who declined to return did so of their own choice.

Former Nam San Yang resident La Nu now lives with his relatives in Myitkyina Township. He told Frontier that his family’s house had been destroyed in the fighting and there was no clear plan for those whose property had been damaged. He recently visited Nam San Yang but has no immediate plans to return there, he said.

Those who have gone back are likely to find few employment opportunities, he added. Previously most of them had worked as traders sending goods to and from China. With the road to Laiza currently shut to trade due to the conflict, this would not be an option until a ceasefire is signed and implemented.

“There are also no security guarantees for people in Nam San Yang,” he said. “If conflict resumes between the military and KIA, they will be in great danger.”

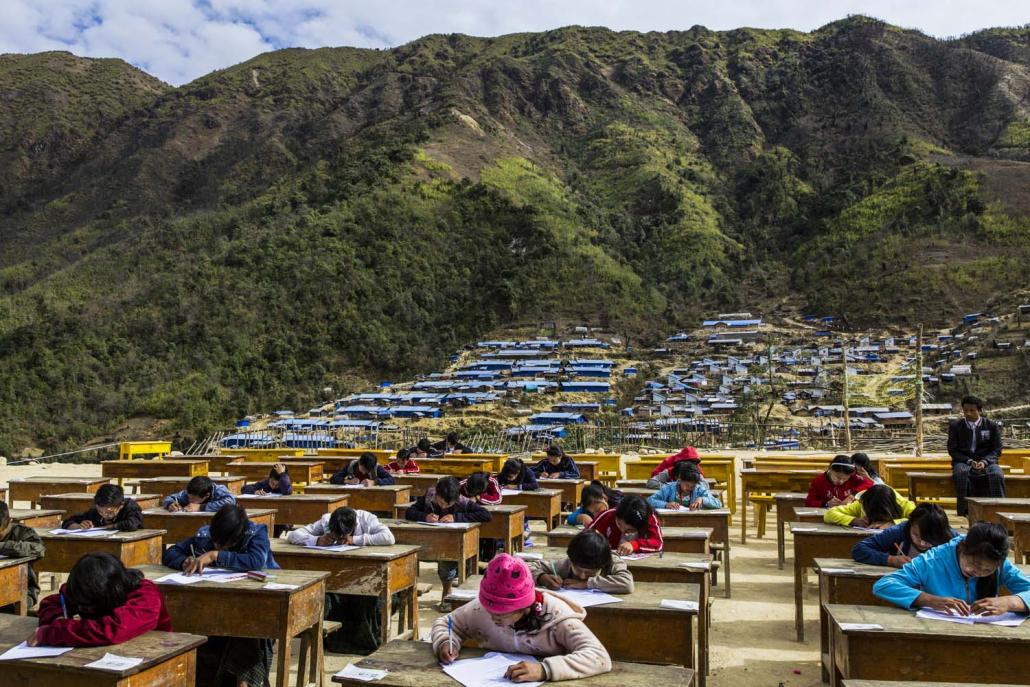

Youth displaced by conflict sit exams at the Hpare camp in Chipwi Township. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

‘We don’t trust the government’

In June, Frontier travelled to Kachin State and visited several IDPs camps in Myitkyina and Chipwi townships. In all interviews, camp residents told Frontier that they wanted to return to their former homes rather than be resettled in a new location.

Hpare camp, in the Panwar area of Chipwi, is home to about 900 people, making it one of the largest IDP camps in the state, according to camp leader Sau Zung. The majority of residents fled their homes in Hpare village, nine miles from the camp, in 2011, shortly after the fighting erupted.

Because the camp is in KIO-controlled territory, it receives little assistance from humanitarian groups, particularly since the government tightened controls on aid in June 2016.

There has been no fighting in the area since 2013, when KIA and Tatmadaw soldiers reached an informal non-aggression pact and later established a “Peace House”, a small shack in the no man’s land between the two frontline positions, where Tatmadaw and KIA soldiers exchange food, drinks and companionship. However, camp residents have not been able to return to their homes because it is still too dangerous.

Resident Hkwang Lin told Frontier she had recently visited Hpare village to check on the home and farm she had left behind but would not go back permanently unless the KIO gave her the green light because of the risk of renewed fighting and landmines.

“If there are security guarantees for us, we will consider returning home. We all want to return home because we are not happy and we are frustrated to be stuck here,” she said.

In Trinity camp in Myitkyina Township, Seng Hpar said she could not return to her home in Injangyang Township’s Bon Swe Yang village because the area had been contaminated with landmines. The camp is home to 853 people from Injangyang who were displaced in 2018.

The experience of those who have returned to Nam San Yang has also made her more cautious.

“I’ve heard that the Nam San Yang villagers don’t feel safe since they returned,” she said. “We don’t trust the government. We want them [the government and military] to guarantee our security.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Internews Myanmar.