EDITORIAL

The country’s economic predicament is inseparable from its political crisis. To help resolve it, foreign nations must go beyond the old playbook of symbolic sanctions and empty statements.

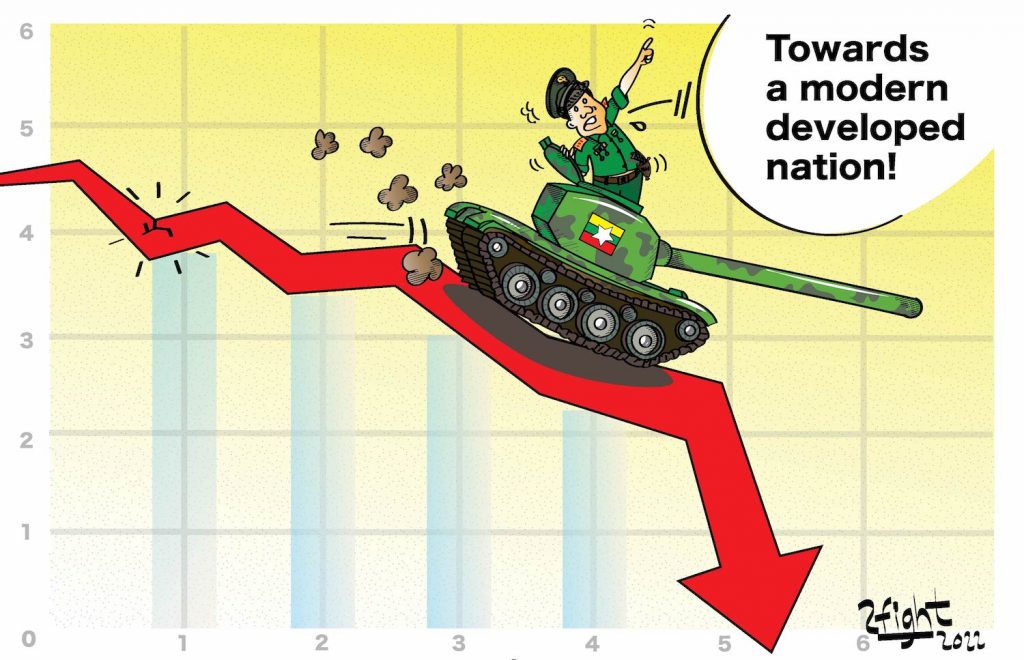

Shuttered petrol stations, medicine shortages and long queues to buy subsidised cooking oil. Welcome to Min Aung Hlaing’s Myanmar – a country that, in the junta chief’s mind, could reach middle-income status within five years and be on par with Singapore in 10.

Despite these delusions, which Min Aung Hlaing aired in a recent meeting of the State Administration Council, he appears to grasp that all is not well with the nation’s finances. Much of his economic policy has consisted of panic moves, including the forcible conversion of foreign currency in bank accounts and the throttling of even essential imports such as medicine and cooking oil. Through a pliant Central Bank and new committees stacked with senior military officials, the regime has intervened in the economy to a level not seen in Myanmar for more than a decade.

In the right hands, state intervention can serve sound industrial policy. Asian powerhouses like South Korea became developed and prosperous by protecting domestic industries and fostering national conglomerates that exported to the world. Yet, far from revealing a radical new programme for economic development, the junta’s erratic decision-making suggests its only real priority is maintaining its hold on power.

Tragically for the tens of millions of people affected by the regime’s decisions, the situation is unlikely to improve. The economic crisis is merely a symptom of the real problem that ails Myanmar: the illegitimate junta and its determination to crush all resistance to perpetual military rule. It may recognise the challenges in the economy, but stubbornly refuses to see that the only solution involves it giving up power.

Meanwhile, the junta’s economic policies have worsened the very problems they have sought to address or simply spawned fresh ones. While the regime has rolled back or adjusted some of its more destructive measures, rapid policy shifts present their own problems. Few investors, whether foreign or local, will be tempted to embark on new ventures under rules that may change overnight.

Besides incompetent management, widespread conflict and reputational risks have also put off foreign investors. This is clearly evident in the power-generation sector. Announcements about new hydropower projects and solar farms are largely just words; tenders keep having to be reissued because so few companies are bidding. The lengthy power cuts of this year’s hot season were just a foretaste of the literal darkness to come under military rule.

Also, regardless of official competence, the people of Myanmar are unlikely to place much trust in financial institutions that are under the thumb of an illegitimate junta, which has proven time and again that it doesn’t have their interests at heart. It is perhaps the clearest illustration of how the country’s economic predicament is inseparable from its political crisis. There is no policy fix, and no way to deliver prosperity in the face of nationwide resistance.

It may be tempting to welcome economic collapse as a forerunner of the regime’s own demise. A bankrupt junta won’t have the cash to buy Russian warplanes or fuel its tanks, and a population driven to the brink is liable to come back out onto the streets, regardless of the dangers, or join the armed resistance in greater numbers.

However, desperation can also work to the regime’s advantage. A person without income is more likely to inform on members of the resistance in exchange for money or other perks, or to accept a post as a local administrator that comes with opportunities for collecting bribes. Because the regime can print kyat, it can also keep paying its civil servants and soldiers, making employment by the junta-controlled state one of the few secure sources of employment. While excessive money-printing can create runaway inflation, the regime would take this over the total collapse of its administration.

A largely crowd-funded resistance movement will also have even less money to equip troops if its domestic supporters can no longer afford to donate. In addition, the cost of foreign-made black market weapons and imported ingredients for making bombs has shot up in tandem with the decline in the kyat; resistance sources say the price of smuggled gunpower from India and Thailand has tripled this year.

This is not to mention the incalculable suffering that further economic decline would inflict on the population, and which a junta cloistered in Nay Pyi Taw would be largely shielded from. Instead, it is incumbent on everyone supporting democracy in Myanmar to think of creative ways of pressuring the regime while sparing the people as far as possible.

United States sanctions on oil and gas, for instance, could deprive the junta of its biggest source of US dollars. However, to work as intended, these sanctions would need to be accompanied by careful diplomacy with Thailand, the main buyer of Myanmar’s gas. Thailand will need to be presented with, and possibly assisted in obtaining, an alternative energy source, or be persuaded to pay gas revenue into an escrow account when its instinct might be to find a workaround with the regime. The latter would be preferable to avoid production shutdowns that would deprive millions of people in Myanmar of electricity, marking the moment when sanctions cease being “targeted”. Unfortunately, Washington appears to lack anything like the necessary bandwidth. Sanctions can be part of effective strategies involving a range of other foreign policy tools, but on their own they are often a lazy substitute for strategy.

As the initial rush of protest and armed revolt has matured into what is likely to be a long, gruelling conflict, cool heads and a sober strategy need to prevail. Although they have been a powerful symbol of opposition to the regime, it is clear by now that public sector strikes in health and education will do little to weaken a military whose decades-long grip on power in Myanmar has never been based on the provision of public services. Conversely, a laser-focus on the material foundations of military rule – from natural resource extraction to the foreign currency needed to buy advanced weapons systems – just might bring the junta to its knees, or at least the negotiating table.

In undermining these foundations, sympathetic countries have an important role to play. However, they first need to go beyond the old, failed playbook of written condemnations, photo-ops with visiting democracy activists and sanctions issued in the absence of a broader strategy. US sanctions on oil and gas would be one possible place to start.

None of this will be easy, but Myanmar’s crisis will not go away if the world ignores it, or simply passes the buck to ASEAN. The junta is the chief source of the economic turmoil that is inflicting misery on millions of people, and it will carry on doing damage until it is forced to go or change course.