The realm of the king of the Konyak Naga covers 40 villages in Myanmar and India and the border runs through the middle of the home where he grants interviews beside a traditional hearth.

By RAYMOND PAGNUCCO | FRONTIER

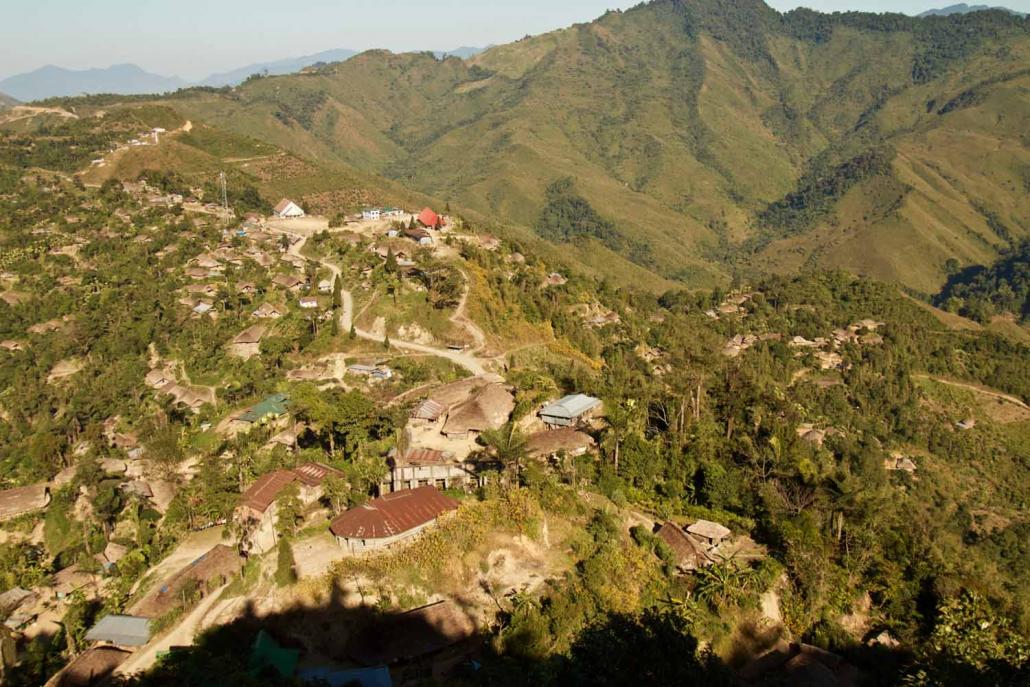

THE MOUNTAINOUS northeastern Indian state of Nagaland is a place of great natural beauty and a complicated legacy of the colonial era.

Bordering Myanmar’s Sagaing Region, Nagaland is bounded by three of the Seven Sister States of India’s northeast: Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Manipur to the south and Assam to the west. The region is known for its ethnic and religious diversity: Nagaland is home to 16 different former headhunting tribal groups known collectively as Nagas.

The problematic legacy bequeathed on Nagaland by the British colonial authorities affects the village of Longwa in Mon district, which straddles the border between India and Myanmar.

However, Longwa is more than just a legacy of boundaries from the colonial era;

it is the capital of a “kingdom” comprising 40 Konyak Naga villages, some of which are in Myanmar.

The kingdom is ruled by an Angh, or king, named Tonyei Phawang, whose lineage is derived from his great-grandfather, a prolific headhunter who took many trophies.

longwa_-_1.jpg

title=

Tonyei Phawang has been king since his father, the former Angh, died 18 months ago. The Angh’s jurisdiction over his realm long preceded the imposition of national boundaries.

When visitors arrive at Longwa, they are told that it is customary for their first stop to be at the house of the Angh where they should show respect by presenting him with a gift.

The Angh’s house is a long, single-storey ferroconcrete building with a big, brick-red corrugated iron roof in the style of a traditional Naga home. Visitors are greeted at the entrance to the building by a collection of wood carvings, water buffalo skulls and the bizarre statue of a cryptid with a bear’s head and the body of a brontosaurus. According to local legend, the creature once roamed the surrounding jungle-clad hills.

Inside is a spacious hall decorated with the skulls of various animals, elephant tusks, gongs, a traditional log drum and photos of previous Angh.

I was ushered down a long corridor with doors on either side, at the end of which was a large kitchen with a traditional Naga hearth set into the floor, where I was introduced to an unassuming man about 5 feet 5 inches (167 centimetres) tall and told he was the Angh.

I presented him with a kilogram of tea and a pocket knife. He graciously accepted my tribute and in return presented me with three cheroots.

“You can’t get these in India, they are from Myanmar,” he said with a smile, and invited me to sit beside him on the hearth.

The Angh produced a water pipe and began to reveal snippets of information about the source of his power and the challenges involved in being in charge of a realm divided by two nations.

Puffing gently on his pipe, the Angh explained that the border ran through the centre of his home and that we were technically inside Myanmar. “When it rains, some of the water runs off the roof on the Indian side and some on the Myanmar side, but I am in the middle,” he said.

“We have customary laws that have been passed down by our forefathers and we have administrative laws that were given to us by the government of India,” the Angh said, speaking slowly.

“There is a council made up of other members from my kingdom that handles the laws. When a decision is to be made we get together to reach an agreement but the final decision is given by me and must be obeyed.”

The Angh explained that despite his exalted position among the Konyak Naga, it did not mean that he has absolute power or that his authority was always recognised.

gun_smith_-_1.jpg

title=

The Angh said that before Myanmar began its transition towards democracy in 2011, members of the Tatmadaw often entered his realm on the Myanmar side and took livestock from his subjects without paying. He also alleged that they would come at night to abduct villagers and force them to be porters.

The Angh said the Tatmadaw had stopped harassing his people five years ago and the situation in his realm on the Myanmar side of the border has become quieter.

Asked why the Indian Army, which has an outpost in the village, did not intervene, the Angh said: “It is like this… this is the border, the Indian Army can’t come here because this is Myanmar; they cannot cross the border and the Myanmar Army knows this”.

As I continued my conversation with the Angh I began to understand that one of the reasons why his home straddles the border is because his subjects rely on his relationship with the Indian government for their survival.

His home’s location enables him to act as a bridge for his subjects and gain access to materials acquired in India to build houses, schools and churches on land that is technically in Myanmar.

When measles was reported in Khamlao village during an epidemic in the Naga Self-Administered Zone in Sagaing last July, the Angh was a lifeline for his people in Myanmar.

“My first duty was to prevent the disease from spreading; I was afraid at the time because if the disease could not be contained all 40 villages would suffer,” said the Angh. “I distributed food and medicine that we received from the Indian government to the Myanmar side of the border. Unfortunately, many children died, maybe around 100,” he said, giving a much higher death toll than that reported in Myanmar.

The epidemic was reported in August to have claimed at least 68 lives in the SAZ, including 40 children aged under 10. Efforts by the Myanmar authorities to bring the epidemic under control were hampered by the remote location of many villages, poor communications and what Naga groups said was a slow response from health teams.

After he finished smoking his pipe, the Angh apologised for not being able to show me around the village, saying he needed to attend the funeral rites of a subject who had died.

He stood, shook my hand and thanked me for visiting Longwa. “Please come back again,” he said. Then the unassuming king of a realm straddling two countries walked away to be with his people.

Top photo: Tonyei Phawang has been the Angh, or king, of the Konyak Naga since his father, the former Angh, passed away 18 months ago. (Raymond Pagnucco / Frontier)