One of the first British servicemen to land in Rangoon during the Japanese retreat in World War II pays an emotional visit to the site of a deadly gunboat battle.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

Ken Joyce was bracing for a fight when his gunboat powered up the Yangon River on May 2, 1945.

The longest British campaign of World War II was drawing to a close. After years of retreat, General William Slim’s 14th Army was streaming south through central Myanmar, and the Japanese defeat seemed all but assured. Bogyoke Aung San’s Burma National Army had recently defected to the British side, and the race was on to capture Rangoon before the monsoon rains began.

But as the invasion force approached the city, in what was known as Operation Dracula, the ferocity and tenacity of the Japanese troops was never far from their mind. Few expected them to completely abandon the prized capital of then-Burma.

Mr Joyce, now 90, recalls seeing the Shwedagon from a distance, and then his vessel pulling in at a wharf at the southern end of Brookings Street (now Bogalay Zay Road). “We were alongside the wharf expecting enemy fire,” he says.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

1_ww2_landing_craft.jpg

(Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia Commons)

Instead, Joyce and the rest of the 23-man crew found abandoned gun emplacements, deserted roads littered with Japanese wartime currency and stinking warehouses full of rotting rice. As a Scot, he was particularly taken by signs for the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company that proclaimed the firm as incorporated in Glasgow.

“We were welcomed by throngs of Rangoon inhabitants who confirmed the news of the Japanese departure,” he says. “It was strange to walk the streets in this large city and see only a handful of inhabitants.”

Whether they were welcomed as liberators or simply saviours is unclear. Rangoon, once described as the “Garden City of the East”, had been devastated by the war, particularly a recent Allied bombing campaign. By May 1945, the city had been without electricity, water or public transport for months. Disease was rife and gangs of dacoits were roving the city.

Crime only increased after the Japanese fled on April 23, in a doomed attempt to cross the Sittaung River and regroup in Mawlamyine.

The withdrawal prompted an outbreak of looting, and the bodies of civilians, apparently members of looting mobs, were still a conspicuous presence on the roads when the British arrived.

A few lingering Japanese, including a sniper who strapped himself to a crane on the harbour, were soon neutralised. More than three years after Rangoon had fallen, it was back in British hands, with barely a shot fired.

Quiet celebrations

The city remained subdued for several weeks, as the main British force had to wait for minesweepers to clear the Yangon River. Joyce and his colleagues had the run of the town, and they celebrated the night of May 2 with large bottles of beer that had earlier been “scrounged” from a larger ship off the Rakhine coast.

“To make them drinkable we put them in a sack and lowered it down to the river bed. By the evening it was ice-cold,” he said.

To break the monotony of tinned food, which was all the small boats carried, they collected some of the Japanese currency that littered Strand Road and travelled out to meet a cruiser, HMS Phoebe. There, they exchanged the cash for a large dinner of roast beef. “I can imagine what they thought when they did arrive and saw the looted banks,” Joyce said.

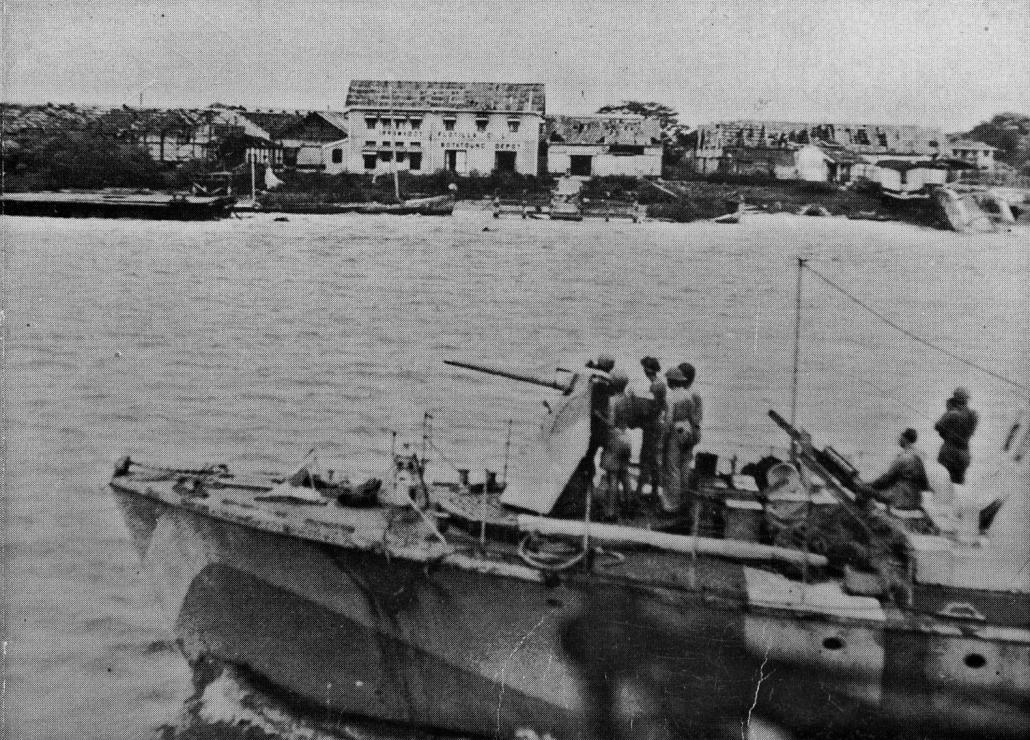

A gunboat entering Rangoon on May 2 passes an Irrawaddy Flotilla Company depot. (Supplied)

On another occasion, after returning to Yangon from a patrol, he was introduced to Tom Joyce, a middle-aged rubber plantation manager for Steel Brothers who had recently been released from an internment camp. They were brought together because of their shared surname, although they were not related.

“It was nearly impossible to get a drink then in Rangoon and I was quite surprised when he took me to the Catholic cathedral [on Bo Aung Kyaw Street] and had the priests invite us into a lounge to drink some strange spirit,” Joyce said. “At the time, I was too young to get a Navy rum allowance and only had an occasional drink of beer!”

Not all British soldiers were pleased at the swift success of Operation Dracula.

In his memoir Quartered Safe Out Here, the writer George MacDonald Fraser, then a young non-commissioned officer in Slim’s 14th Army, described the news of Rangoon’s fall as a “bombshell” for his colleagues, who had been determined to reach the city first but were stopped near Bago by monsoon rains. The atmosphere briefly turned “mutinous” in his section, he wrote.

“The old division that had endured the retreat three years before, had been in the thick of the great battle that stopped the Japs at the gates of India, and led the way south was denied the ultimate prize at the last minute.”

Slim mentions none of this in his autobiography, Defeat into Victory, and perhaps was not aware of the sentiment. He notes only that he wanted the amphibious landing to be “a little later”, but that naval advice had been unanimous this was the latest date possible given the weather. He generously described the operation as a “great achievement”.

For his part, Joyce says the crew of gunboat ML269 were “very much aware that our easy run in taking Rangoon was thanks to the 14th Army”.

While Rangoon was momentarily quiet, Joyce’s war in Burma was not yet over.

8_ken_joyce_2.jpg.png

Ken Joyce is one of the last surviving British soldiers involved in the re-taking of Rangoon from the Japanese in 1945. (Supplied)

Eager to serve

Joyce volunteered for the Royal Navy in 1943, at just 17. He had been desperate to enlist since May 1940; although the war was less than nine months old, two uncles had already been injured and taken prisoner by the Germans. After a few weeks training, Joyce was assigned to Light Coastal Forces, which operated heavily armed wooden motor torpedo boats and gunboats in the waters around occupied France, Holland and Belgium.

After his torpedo boat was severely damaged, he was transferred to ML269, which helped to land Allied forces on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day.

With the French coast secured, the Navy decided to use the landing craft in the war against Japan. Thus ML269 – a wooden vessel 112 feet long and 18 feet wide – was in July ordered to set sail for Burma, 10,000 miles away. It bounced like a cork in the Atlantic for a week, before entering the calm waters of the Mediterranean. From there it was smooth sailing to India – Joyce described it as “a millionaire’s cruise”, for when they stopped at ports along the way they had access to food and other items that had not been seen in Britain since the war began. In Bombay (now Mumbai) the vessels were refitted with armaments that made them the most formidable gunboats of the Burma campaign.

Due to the Japanese retreat, they got little use until two weeks after the invasion of Rangoon, when ML269 joined three other gunboats at a village called Kokkowa, where the Hlaing and Bawle rivers meet to the west of Yangon. At 8pm, two Japanese boats appeared; both laden with drums of fuel that caught fire in the ensuing engagement. The waterfront of the village was also ablaze, and it seemed unlikely any more Japanese craft would pass. Close to midnight, however, three more appeared. Silhouetted against the burning village, they made easy targets. They were all soon despatched, but kept firing until the moment they sank below the water. Fifty Japanese soldiers were killed, said official reports, for the loss of one British sailor.

Four days later, ML269 was in Yandoon (now Nyaungdon), investigating reports of more Japanese vessels in the area. Together with three other gunboats, it ventured up the Ayeyarwady River, hugging its left bank, and finally spotted three vessels hiding behind bushes along the bank. ML269 pulled abreast, firing nearly 20 shells from its six-pound gun, and the Japanese boats quickly burst into flames. It was the last action of World War II for the Royal Navy’s Light Coastal Forces, the war in Europe having officially ended 12 days earlier.

Burma: A lifelong affinity

Like other British and Allied servicemen, the Japanese surrender in August took Joyce by surprise. They had been anticipating a prolonged campaign – possibly one of several years – clearing the remaining Japanese forces from Malaya and the rest of Southeast Asia. ML269 had already been given a target for the campaign: a bridge at Fort Dickson, near Kuala Lumpur.

“We had no idea that the war would end when it did,” he said. “Stretching out before us was the need to capture the many Indonesian islands occupied by the Japs. There was no thought of a Japanese surrender.”

Instead, they turned their boats over to the Burmese Navy in October. Older members of ML269’s crew, some of whom had been in the war since 1939, had already been repatriated, but Joyce stayed in Rangoon.

Shortly after, he was granted leave and visited his namesake’s rubber plantation, near Twante in Yangon Region. It was here that he met Tom Joyce’s daughter, Heather. While the younger Joyce was soon off to fight a “nasty little war” in Java, helping to evacuate Dutch women and children, he and Heather would eventually be reunited in Britain and marry nine years later.

Over the years they kept in touch with events in Burma, donating to charitable projects, particularly orphanages, and meeting Burmese residents who were visiting London.

The 1962 coup shut the door on a return visit; for many years, tourists could only get a 24-hour visa.

However, in late 2004, Joyce and his wife, who were then living in Australia, finally returned. They visited the places they had known many years before, finding Yangon’s downtown little different from 60 years earlier.

In 2006, Joyce came back on his own (the second of four visits), determined to relive his own formative experience in Burma. He had recently been put in contact with Daw Khaing Tun, who ran a travel company specialising in tours for World War II veterans and their relatives.

Early one morning, they set off from Yangon for Nyaungdon, crossing the recently built bridge over the Ayeyarwady. They still had little idea how to get to Kokkowa, but were told by locals to head to the village of Anyarsu. A 30-minute boat ride took them to their destination.

Commander of the French Armed Forces in New Caledonia, Major-General Philippe Leonard, presents the French Legion of Honour to Ken Joyce onboard the French frigate Fns Vendémiaire at Garden Island, sydney. (Royal Australian Navy / Supplied)

For Joyce, the return was “a most emotional time”.

“We soon found a lady, one year younger than me, who remembered the battle. She described how on that terrible night we had set fire, accidentally, to her village. Her words were translated to me and her last few words were, ‘All the poor Japanese were killed.’

“I tried to make a speech but was too moved and Khaing took over for me. All I could do was empty my wallet as a gift. It was a quiet drive back to Rangoon; it was one of the most emotional moments in my life.”

In December 2015, Joyce was recognised by France for his work during the D-Day landings, receiving the Légion d’honneur together with four other veterans of World War II.

It was a medal he wore with pride as he marched in Sydney on April 25 to mark ANZAC Day, Australia’s annual commemoration for its men and women who served and died in foreign conflicts. Joyce was the only Burma veteran who marched in Sydney, and he knows of only two others left in Australia. In many cases, long-departed veterans of the conflict were represented by their children, grandchildren or other relatives.

For Joyce, the march was a bittersweet occasion; a reminder that he was among the last witnesses to the final days of a war that shaped not only his life, but also the future of the soon-to-be independent nation of Burma.

Title photo: Landing craft carrying troops of the Indian 15th Corps proceed up the Rangoon River as part of Operation Dracula in 1945. (Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia Commons)