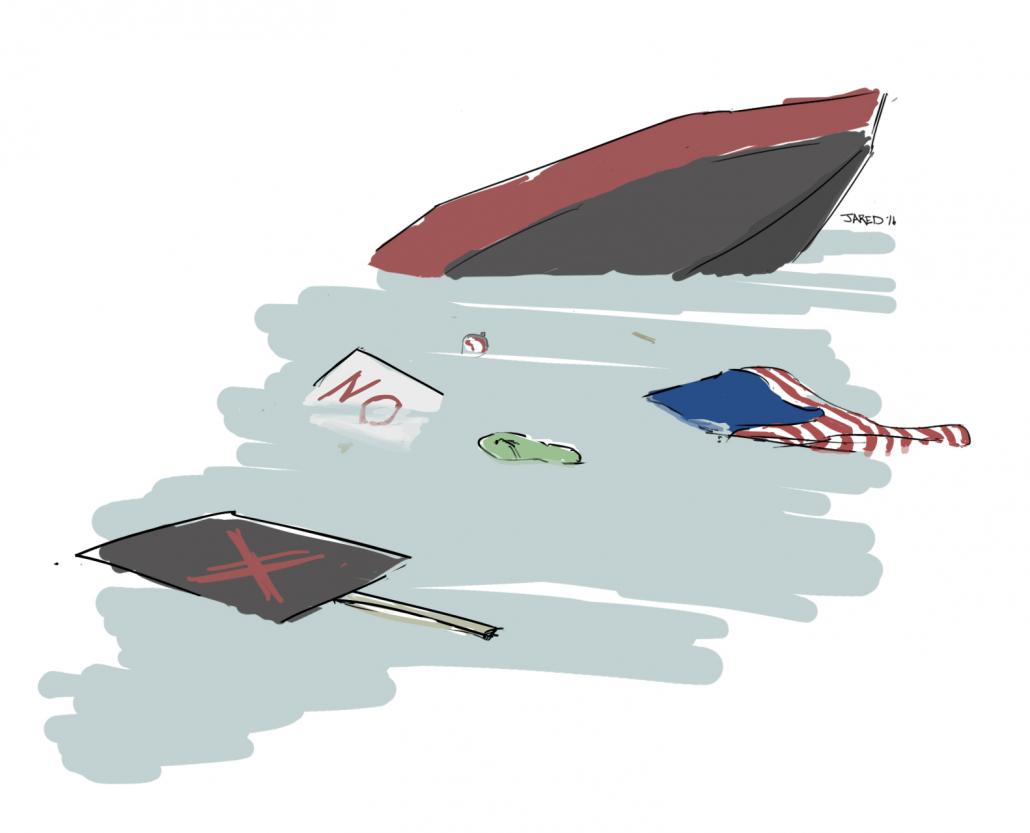

It was an obscenity to use the deaths of those who died in last month’s ferry crash — several of whom were young children — as a political tool.

Last month, at least 21 people died after a boat transporting passengers from an IDP camp to Sittwe capsized off the coast of Rakhine State. At least seven of the dead were aged eight or under; at least two were infants.

Most of the passengers were residents of the Sin Tet Maw camp in Pauktaw Township, established in the wake of the 2012 communal strife that claimed hundreds of lives and displaced almost 140,000 people. In an environment of endemic malnutrition and extreme restrictions on freedom of movement, the passengers had been granted permission for a day trip to the Rakhine capital to buy essential supplies.

It was a tragedy regardless of the identity of those who perished. But to use these deaths as a political weapon is an obscenity. As such, last month’s protest outside the United States Embassy represented a total abandonment of human decency, a new depth in poor taste — even by the standards of a nationalist movement that has cravenly sought to pander to the basest prejudices of its audience.

Around 300 people gathered outside the embassy compound not to condemn the loss of life in the accident, or the appalling conditions in the camps that enabled the loss of life, but to protest the use of the word Rohingya to describe those who had died. To add a measure of farce to the tragedy, the Myanmar Times has since reported that the victims were Kaman, a predominantly Muslim and formally recognised ethnic group who trace their ancestry back to the independent Arakan kingdoms that pre-dated British colonial rule.

The fact that the Myanmar National Network had the audacity to describe the use of the term Rohingya “an effort to intentionally provoke social and religious conflicts” also suggests a serious lack of self-reflection on the part of these activists. In recent years their movement has helped fan the flames of sectarian violence against Muslim communities in Rakhine State, Meiktila, Mandalay, Lashio and elsewhere.

Organisers of the protest would like the international community to believe their grievances are legitimate. Many scholars and international observers have questioned the Rohingya community’s claims of continuous settlement spanning centuries, and posited that the label is better understood as a political rather than an ethnic construct.

Organisers of the protest would like the international community to believe their grievances are legitimate. Many scholars and international observers have questioned the Rohingya community’s claims of continuous settlement spanning centuries, and posited that the label is better understood as a political rather than an ethnic construct.

Jared Downing / Frontier

Some experts, well-intentioned and seeking a pragmatic solution to the humanitarian crisis currently underway in Rakhine State, are even supportive of the government’s refusal to allow the Rohingya community to self-identify as such — a right enjoyed by the vast majority of the people living in this country, and one reaffirmed by successive US ambassadors here.

The debate over these questions of identity is as arcane as it is irrelevant. The groups that initiated this protest are not compelled to act by their opposition to the term Rohingya. Time and time again, they have shown that their true motivations are steeped in total opposition to the descendants of colonial-era migration from British India, and their continued presence in this country.

Their attitudes reflect a view that predominates at senior levels of Myanmar society. New Religious Affairs Minister Thura U Aung Ko last month used the terminology of the 1982 Citizenship Act to refer to these colonial descendants, both Muslim and Hindu, as “associate citizens”. The Immigration Ministry’s motto remains a testament to fears of a foreign influx: “The earth will not swallow a race to extinction, but another race will.”

By capitalising on last month’s tragedy in Rakhine State in this manner, the protest leaders have demonstrated their lack of belief in their shared humanity with the victims. They have also demonstrated their desperation. Less people are attending these nationalist rallies than two years ago. More young campaigners are protesting loudly and publicly to condemn the spread of hate speech. Given nationalist groups campaigned enthusiastically for U Thein Sein in last year’s election, the new government is unlikely to be as indulgent of their demands and their caprices. Perhaps that makes them more dangerous than ever: a beast never fights harder than when it is threatened.