Five residents of a Rakhine State village have served time in jail amid a bitter dispute over an ancient monastery that has split the community.

By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

AT FIRST glance, Mu Rwing village, with its spacious compounds sheltered by shady trees, seems quiet and peaceful, but its appearance is deceiving.

Mu Rwing, about 48 kilometres (30 miles) south of Kyaukphyu town in Rakhine State, has been torn apart by an acrimonious dispute over the closure of a Buddhist monastery.

The unseemly dispute has left the monastery in the northern part of Mu Rwing closed twice since 2007 at the orders of the supreme body representing the monkhood. Opposition to the move has resulted in the jailing of five of the monastery’s supporters in the village of 300 households.

The deterioration in relations among the Buddhists in Mu Rwing meant that the village was “like a disease covered by a beautiful blanket”, said U Phoe San, 62, one of the northern residents affected by the monastery’s closure.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The roots of the dispute date to 2005, when the congregations attending Mu Rwing’s three monasteries agreed to a plan to merge them into one, to be built at a new site.

The plan had the support of the monasteries’ three abbots and a monk named U Supiya, who was originally from Mu Rwing but had been living at a monastery in Yangon’s Yankin Township. The idea was to emulate other villages that had adopted a “one monastery policy” as a means of improving village unity.

In Mu Rwing, though, it has had the opposite effect.

The three monasteries, or kyaung, were named according to their location, age or both: Kyaung Ahaung (“old”), in the northern part of the village, Taung (“south”) Kyaung, in the south, and the most recent, Kyaung Thit (“new”).

As its name suggests, Kyaung Ahaung – also known as Myauk (“north”) Kyaung – is the oldest and is believed to have been built about 880CE, when the village was established during the Rakhine kingdom of Waithali.

During the negotiations on the new monastery it was agreed that it be built at a location distant from the others.

However, the building of the new monastery near Taung Kyaung infuriated supporters of Kyaung Ahaung, sparking the feud that has divided families and split the village. Five residents of the northern part of the village were jailed for six months in 2015 for mischief and trespassing because they continued to attend Kyaung Ahaung.

The dispute erupted in 2007 after U Obhasa, the abbot of Kyaung Ahaung and a resident for 19 years, was expelled and the monastery was ordered to close by local authorities.

The closure followed the intervention of two powerful senior monks who were acting with the support of a majority of village residents, including those from its southern side.

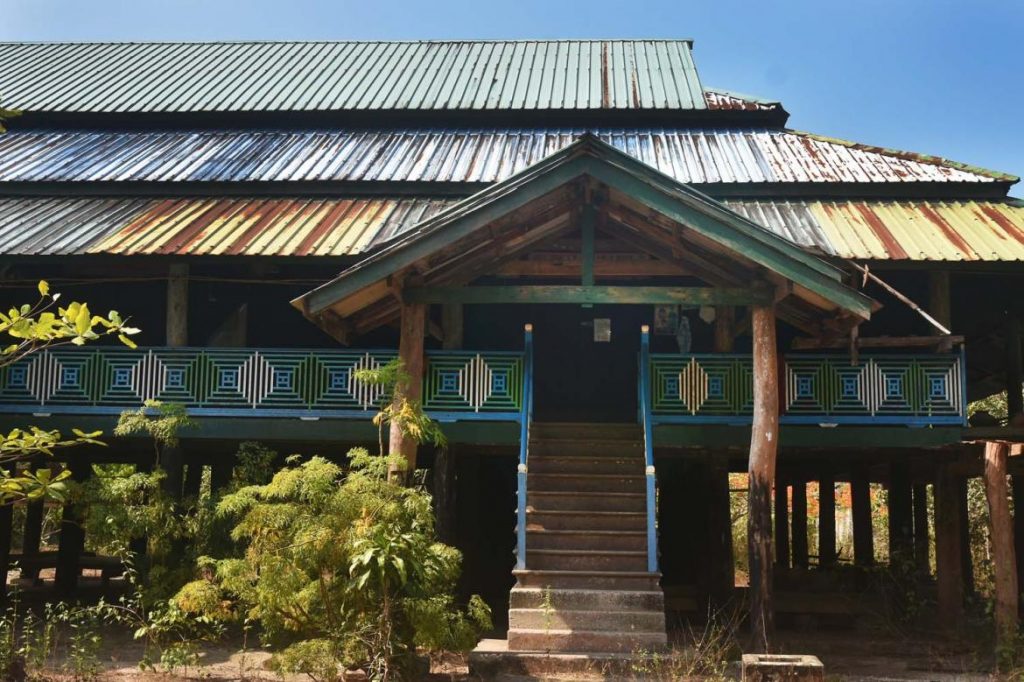

Today the gates are padlocked. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)

The two monks, U Cakkinda and U Pannavamsa, are originally from Mu Rwing and are former teachers of Supiya.

Cakkinda is a former head of the Kyaukphyu branch of the supreme body representing the monkhood in Myanmar, the State Maha Sangha Nayaka Committee, which is better known by its Burmese acronym, Ma Ha Na.

Pannavamsa is a former member of Ma Ha Na, which comprises 47 sayadaws from the country’s nine main Theravada Buddhist sects. Cakkinda and Pannavamsa are members of the dominant Thudhamma sect, which comprises up to 90 percent of all Buddhist monks.

The closure of Kyaung Ahaung in 2007 was opposed by monks from the Wa-mhyaung branch of Thudhamma and in March 2011 20 of them reopened the monastery and chose U Somana to be its resident abbot.

“We reopened the monastery because we could not leave it abandoned; it has historic significance,” said U San Chit, 63, one of the five lay supporters of Kyaung Ahaung who were jailed in 2015.

The reopening occurred after Ma Ha Na issued an ambiguous statement on the dispute, ordering a “stop” – a stop to what was unclear – and saying that it would not accept any complaint from either side.

“We understood from the statement that we could re-open our monastery,” San Chit told Frontier.

A Buddha image inside a Dhammayone within the Kyaung Haung compound. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)

He has been lobbying Ma Ha Na members in Nay Pyi Taw, Mandalay and Yangon to have the monastery re-opened but so far his efforts have been in vain.

San Chit said he had recently also sought the intervention of the Kyaukphyu township administrator was told to “ask U Cakkinda”.

In 2015 villagers opposed to the re-opening of Kyaung Ahaung wrote to Ma Ha Na and are alleged to have falsely accused U Kesarindha of staying at the monastery, where Somana had been living for four years.

The letter escalated the dispute.

Kesarindha, abbot of the Thintaung monastery in Kyaukphyu for 10 years, is a member of the Wa-mhyaung sect and was involved in the re-opening of Kyaung Ahaung.

U Varasami, secretary of the township Sangha Nayaka, said the accusation against Kesarindha was probably because of his involvement in unsealing Kyaung Ahaung.

Defending the decision by Ma Ha Na to close the monastery, Varasami said it was taken in order to ensure unity.

Kesarindha said the decision to seal Kyaung Ahaung was wrong because there was no procedure for shutting a monastery while it was the subject of a dispute.

In a letter dated January 16, 2015, Ma Ha Na instructed Kesarindha to leave Kyaung Ahaung and ordered the monastery to be sealed again.

“I never lived there and everybody knows it,” Kesarindha said. “If they were real Buddhist monks they would not do this to me and the people who support Kyaung Ahaung.”

In April 2015, the monastery was forcibly closed, despite a petition to the government from 98 Wa-mhyaung monks asking that it remain open.

A protest in the town of Kyaukphyu last July over the closure of the monastery was attended by about 300 lay people and Wa-mhyaung monks.

U Phoe San, 62, who lives in northern Mu Rwing, said that after the three monasteries agreed on a new monastery the plan went awry and divided the community.

“They [monks] said they did it with good intentions, but now we are divided. We have to ask ‘why’,” Phoe San told Frontier on May 15.

“Kyaung Haung was not shut down because it breached the rules of Buddhism, but because we were browbeaten.”

He said powerful monks such as Cakkinda and Supiya had promised that none of three congregations in the village would be at a disadvantage by the plan for a new monastery and alleged they had later broken the pledge by favouring a majority of residents.

Daw Aye Phyu Ma, 75, and other residents of the northern section of Mu Rwing have been banned from the village’s market and using its well in the wake of the monastery dispute. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)

The impact of the dispute on the village has been severe. The 60 households in the north of the village have been banned from using the market and well in the south of the village by order of the local administrator.

Phoe San said that until shops began opening in his part of the village, its residents had to do their shopping in other villages. They’ve also had to sink new wells.

He said the closure of the monastery was in breach of the constitution, in which article 34 provides for freedom of religion.

The village’s northern residents were prepared to wait as long as necessary to be able to use Kyaung Ahaung again, Phoe San said.

It is common in Myanmar for ageing Buddhists to draw spiritual comfort from spending increasing time at monasteries and temples, and the closure of Kyaung Ahaung has been distressing for elderly residents of northern Mu Rwing. There are about 40 of them, aged between 60 and 103, and they include Daw Aye Phyu Ma, 75.

“I just feel sad and want to cry,” she said, about not being able to visit Kyaung Ahaung.

“When they [opponents of Kyaung Ahaung] are happy, we cry,” said Daw Pa Pa Mhyaing, 36, who lives next to Kyaung Ahaung. Her husband, U Maung Than Zaw, 39, was among the five jailed over the dispute.

“My husband was jailed for being a Buddhist,” an indignant Pa Pa Mhyaing told Frontier on May 15.

“We faced many difficulties because he is the family’s only breadwinner,” she said, adding that their daughter was just five months old when her husband was jailed.

The day Maung Than Zaw was released from prison six months later his daughter called him “Pa Pa” for the first time and he became emotional, Pa Pa Mhyaing recalled. “He cried because he had missed her so badly.”