A new primary school curriculum makes some important steps forward, but more work is needed to promote social inclusion and contribute to lasting peace.

By ROSALIE METRO | FRONTIER

FOR SEVERAL years, Myanmar’s Ministry of Education has been collaborating with the Japan International Cooperation Agency to revise the primary school curriculum. Under the National Education Strategic Plan, one of the goals is to create a curriculum “more relevant to all students” and to improve inclusion and equity while promoting critical thinking. This is good news. Scholars, myself included, have observed that previous textbooks, centred on Bamar Buddhist warrior kings, have pushed ethnic and religious minorities to the margins, deepening social divisions.

In any country, it is difficult to create an inclusive curriculum that promotes peace, and it is clear that the people working on Myanmar’s new textbooks are doing so with the best intentions, despite a tight timeline, resource constraints and complex dynamics among government, non-government and inter-governmental stakeholders.

Although it is too soon to judge the entire curriculum, the kindergarten to Grade Three textbooks in use indicate the direction the revisions have taken. There is much to commend. Blatantly offensive content, such as a poem maligning people of “mixed blood,” has been removed. However, subtle biases favouring powerful groups still permeate the curriculum. As an anthropologist of education who has studied former and current curricula, I would like to suggest 10 steps that could be taken to improve social inclusion and promote peace in forthcoming textbooks and re-issues of those in use.

1. Diversify the ethnic and religious identification markers – including names and skin colours – of characters shown in textbooks, so that more children can see themselves represented.

Although every story, every piece of information, and every image, provides an opportunity to help children feel included, many such chances have been missed. Mathematics problems, for example, feature children with Bamar (Burman) or generically Myanmar names (e.g., Htun Htun, Su Su) and not those with recognisably ethnic or religious minority names (e.g., Bleh Wah, Mohammed). Adding a wider variety of names is an easy way to broaden the boundaries of who feels included. Additionally, the new artwork indicates subconscious biases against people with dark skin. Unfortunately, people perceived as having dark skin, especially Muslims and those of Indian descent, have long faced discrimination in Myanmar. Although the curriculum encourages children to make friends of all colours and science textbooks mention skin tone variation as normal, the illustrations tell a different story. Children may get the sense that their own skin colour or the skin colour of their classmates is undesirable. Illustrations showing realistic variations in skin tone among Myanmar people could increase kids’ self-esteem.

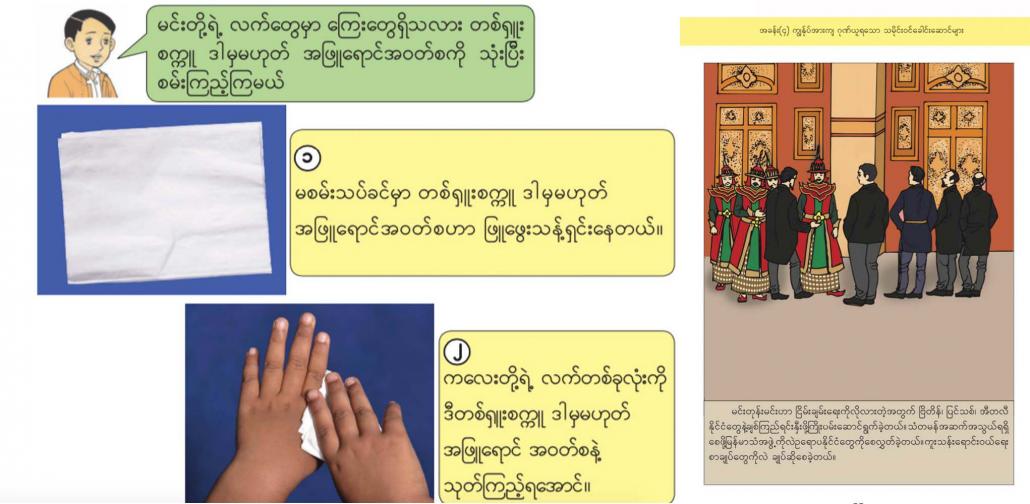

1_skin_tone.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

A First Grade Life Skills textbook shows the contrast between a child’s skin colour and the cartoon illustrations (left) and a Third Grade Social Studies textbook shows Myanmar and European people having the same skin tone.

2. Represent women more broadly, so that girls are not limited by stereotypes.

In the new textbooks, every “hero” featured in social studies textbooks is male (with the exception of Queen Shinsawpu). One unfortunate result of sexism is that women were less likely to hold power and their part in history is much less widely known. Yet there are women who could have been included: the ancient queen Saw Mon Hla, and modern figures such as Daw Mya Sein, who addressed the British parliament in 1930 asking for the British to rule Burma separately from India; or Dr Cynthia Maung, a Karen doctor who opened a clinic for refugees in Thailand. Profiling only men creates the mistaken impression that women have contributed little to the country.

When women are portrayed, it is often in stereotypical ways. Women are shown almost exclusively in helping professions such as teaching and healthcare, and are often portrayed doing housework and childcare; men are shown as farmers, soldiers, and scientists. There are some welcome exceptions to this trend, but it would be wonderful to show women excelling in a wider variety of pursuits.

3. Expand representation of historical and contemporary figures beyond the Bamar ethnic group, so that more children feel part of the Union.

Not only are almost all “heroes” in these textbooks male, they are also almost all Bamar. However, because all ethnic identifiers have been removed from the new social studies textbooks, this is not readily apparent. So Bayinnaung fights nameless enemies instead of the Mon at the Battle of Naungyo, and Queen Shinsawpu is only identified as being “from Hanthawadi.” While clearly intended to spare young children from the former narrative of Bamar domination over other ethnic groups, this approach erases non-Bamar from history.

This is a missed opportunity to build mutual respect, as there are many ethnic minority figures who could have been profiled, both in ancient and modern times. They include the Rakhine king Min Saw Mon, who founded the kingdom of Mrauk-U, or Sao Shwe Thaike, the Shan first president of Burma. It would also be appropriate to include admirable people of Indian and Chinese descent, many of whom have lived in Myanmar for generations. The former curriculum mentioned them rarely and only in negative ways, which is damaging for children from these groups.

In a positive step forward, each state is being allowed to develop a “local curriculum” to be used alongside the central one, which may partly remedy this erasure of ethnic minorities. Yet it is not clear what students and teachers are supposed to do if these curricula contain contradictory information – for example, if the local curricula identify Bamar kings as oppressors rather than unifiers. The fact that the central curriculum is so Bamar-centric is likely to make the contrast between the two curricular strands more problematic; adding more ethnic minority figures could help bridge the gap.

4. Introduce the idea that children have rights, so they can begin advocating for themselves.

Among the most groundbreaking elements of the new curriculum are lessons from the Life Skills textbooks on preventing sexual abuse. Students are told to object if an adult touches them in an inappropriate way – a suggestion that goes against cultural norms that children should always obey their elders.

Yet children are not explicitly told that they have the right to be protected from sexual abuse and that the government has a role in providing protection. Nor are they told that they have the right to an education, to speak their mother language, be secure in their homes, be free from discrimination, to practice their religion or to express their ideas.

Despite Myanmar being a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the concept of rights is omitted from the curriculum. Instead, children are told about their responsibilities. This focus on duties permeates the Morality and Civics curriculum.

For example, children are shown helping to re-excavate a reservoir by carrying rocks on their heads in baskets. There is no suggestion that they have a right to clean drinking water, or that the government has the responsibility to provide it. Enumerating children’s rights would prepare them to identify instances where they or their peers’ rights are being violated, and to become advocates for social inclusion.

2_children_excavate_the_resevoir.jpg

A third grade morality and civics textbook shows children re-excavating a reservoir.

5. Introduce Christianity, Islam and other religions practiced in Myanmar, alongside Buddhism.

In an impressive leap toward religious tolerance, a curriculum that once contained only a passing reference to Father Christmas now includes a photo of a Christian church and a description of its Pwo Karen congregation. However, that is the only mention of any religion other than Buddhism, although one in 10 children are not Buddhist.

Muslims, who comprise at least 4 percent of the population, are never mentioned, and neither are Hindus and animists, the next most populous groups. Buddhism clearly enjoys a preferential status in the curriculum. Kings are praised for building pagodas and supporting the sangha, but no one is praised for building mosques or churches. Important Muslim figures such as Abdul Razak, one of the martyrs killed when General Aung San was assassinated, are left out of these social studies textbooks.

Having simple but accurate information about a variety of religions would counter misinformation, about Islam in particular. It would be wonderful to see a story in the Morality and Civics curriculum about a Muslim child and Buddhist child forming a friendship, because such examples could strengthen a social fabric that has been weakened by violence.

3_religion.jpg

A Third Grade Social Studies textbook shows a Christian church (left) and a First Grade Social Studies textbook shows King Anawrahta paying respect to a Buddhist monk.

6. Go beyond the superficial level when representing ethnic minority groups, to increase mutual respect.

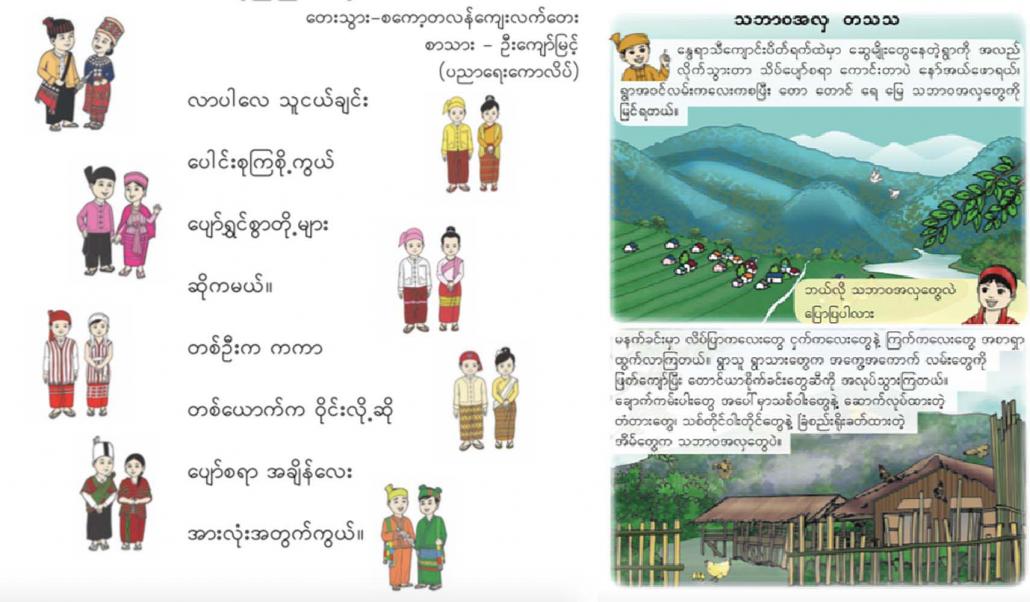

The new curriculum, like the old one, mentions ethnic minorities often, but does so in a specific way, showing images of a man and woman from each of the eight main national races – Bamar, Chin, Kachin, Karen, Kayah, Mon, Shan and Rakhine – gathered around a map of Myanmar or engaged in a display of unity. Texts and poems that accompany these illustrations underscore the harmony and friendship among these eight groups. Clearly, the idea is to provide a positive message to children to counteract the rancour from seventy years of civil war.

However, these superficial portrayals of ethnic unity may not have their intended effect. They do not provide any information about the histories or current circumstances of ethnic minorities. All a child would know about non-Bamar ethnic groups by the end of Third Grade is that they have different traditional costumes. There is little indication that they have languages, cultures or goals of their own. Even a simple step like adding speech bubbles to the eight national races to teach children how to greet each other in their native languages would be an improvement.

On the rare occasions where more space is devoted to ethnic minorities, stereotypes are on display. For example, a story on ethnic minority people in the Morality and Civics curriculum shows them enjoying nature in a small village. Because this is one of the only portrayals of ethnic minority areas, it has the potential to reinforce stereotypes that non-Bamar live in a pre-modern world.

Under the military regime, social studies textbooks outlining the eight main national races described only Bamar as engaging in commerce; the others were depicted as farmers. A story about a computer programmer or businesswoman could have given children a broader sense of ethnic minority people’s lives.

4_national_races.jpg

A First Grade Performing Arts textbook shows the eight national races (left) and a Third Grade Morality and Civics textbook shows ethnic minority people living a small village.

7. Represent Myanmar as a multicultural society, so that “Myanmar” does not merely mean “Bamar”.

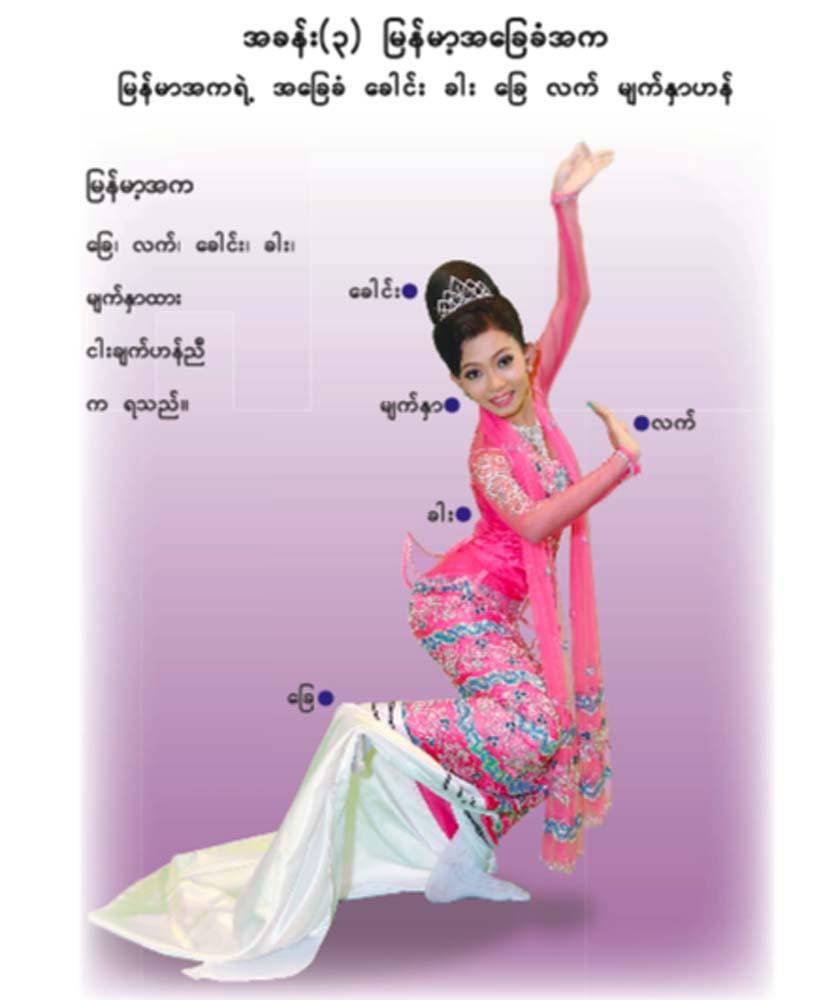

A few symbols of minority ethnic cultures, such as a Kachin manao pole, appear in Myanmar textbooks, but most cultural symbols and practices in the curriculum are Bamar – even when they are identified more broadly as Myanmar. For instance, a Performing Arts textbook shows “Myanmar Dancing” that seems to be Bamar dancing. The “Myanmar” supposedly includes all the national races, but examples such as this show that its de facto meaning is Bamar.

If the term “Myanmar” includes all the national races, why not use it in a way that reflects the multicultural nature of society, such as by showing several traditions of dance?

myanmar_dancing.jpg

A First Grade Performing Arts textbook shows “Myanmar Dance.”

8. Encourage students to think critically about history, so that they can work together for the country’s future.

This curriculum makes a huge step away from rote memorisation and towards critical thinking by asking children open-ended questions, such as “Who are the ethnic groups in your area?”, which allows them to identify themselves and their neighbours as they wish. However, on more controversial topics, students are asked only leading questions.

The First Grade Social Studies textbook asks about the Bamar warrior kings Anawrahta, Bayinnaung, Kyansittha and Alaungmintaya, “Which of the great kings’ accomplishments do you support?” A text about Aung San is followed by the question, “What do you emulate about General Aung San?” Questions like this do not promote a balanced view; instead, they create the impression that leaders are above criticism.

We need only to look at recent cases in which ethnic minority people have opposed statues of Aung San to see that his legacy is more complex. Although the curriculum contains only positive information about its “heroes,” children may well have heard alternate histories from their parents, communities, or, in coming years, from local curricula.

Given the reality of years of bloody civil war, asking truly open-ended questions and encouraging children to form their own ideas about the past and present creates an honest basis for their future collaboration. In response to a genuinely open-ended question such as, “Do you think King Bayinnaung was a good leader? Why or why not?” a child might say, “No, I think he started too many wars.” This would create an opportunity for a real discussion about history.

9. Include primary source documents in history textbooks, so students can form their own interpretations.

Although building children’s critical thinking skills at an early age is crucial, this process can be continued in middle and high school by including primary source documents in the curriculum. For instance, instead of telling students about the Panglong Agreement, why not include the text itself? Then they could see for themselves what it said and who signed it.

They could discuss various interpretations of it, instead of being told – unconvincingly, given the country’s history – that it means all the ethnic groups joined together happily. There are many documents that could be included to illustrate multiple perspectives about history, instead of enforcing only one; I have gathered more than a hundred in my textbook Histories of Burma: A Source-Based Approach to Myanmar’s History.

In the past, each history textbook began with a foreword announcing its aims to promote patriotism and Union spirit. These forewords have been altered to emphasise the need for students to think critically, but the underlying goals clearly remain the same. The problem is not that critical thinking is incompatible with Union spirit or patriotism, but that students have not been free to choose what to be proud of and whom to feel unified with. Including primary documents and teaching students to form their own interpretations could instil a more genuine sense of patriotism and Union spirit, while also building critical thinking.

10. Involve students, teachers and parents in curriculum revision, so that they can contribute their insights.

Although creating the new curriculum involved a limited group of people, the process of evaluating it could be more participatory. Officials from the MOE and JICA could visit schools to observe how the curriculum is being used, and interview students, teachers and parents about how well it is promoting social inclusion, peace, critical thinking and other goals outlined in the NESP. These insights should be captured and disseminated, so it is clear how the feedback influenced future developments in the curriculum.

Educators have argued that curricula should be both a mirror and a window for all children: students should see themselves reflected in textbooks, and they should learn about others’ lives. Yet this curriculum still mostly provides a mirror for Bamar Buddhist boys, while leaving other students on the outside looking in . It is my hope that future textbooks will include more substantive coverage of women as well as ethnic and religious minorities. The new curriculum does not yet reflect the identities and needs of all children who will use it, and in that regard, its potential to act as a force for social inclusion and peace is limited.