Addicts have long been targeted in the war on drugs, but a new policy under discussion may decriminalise narcotics use by recognising that addiction is a public health issue.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

IN OCTOBER, the Myanmar Police Force began officially discussing a new drug enforcement policy.

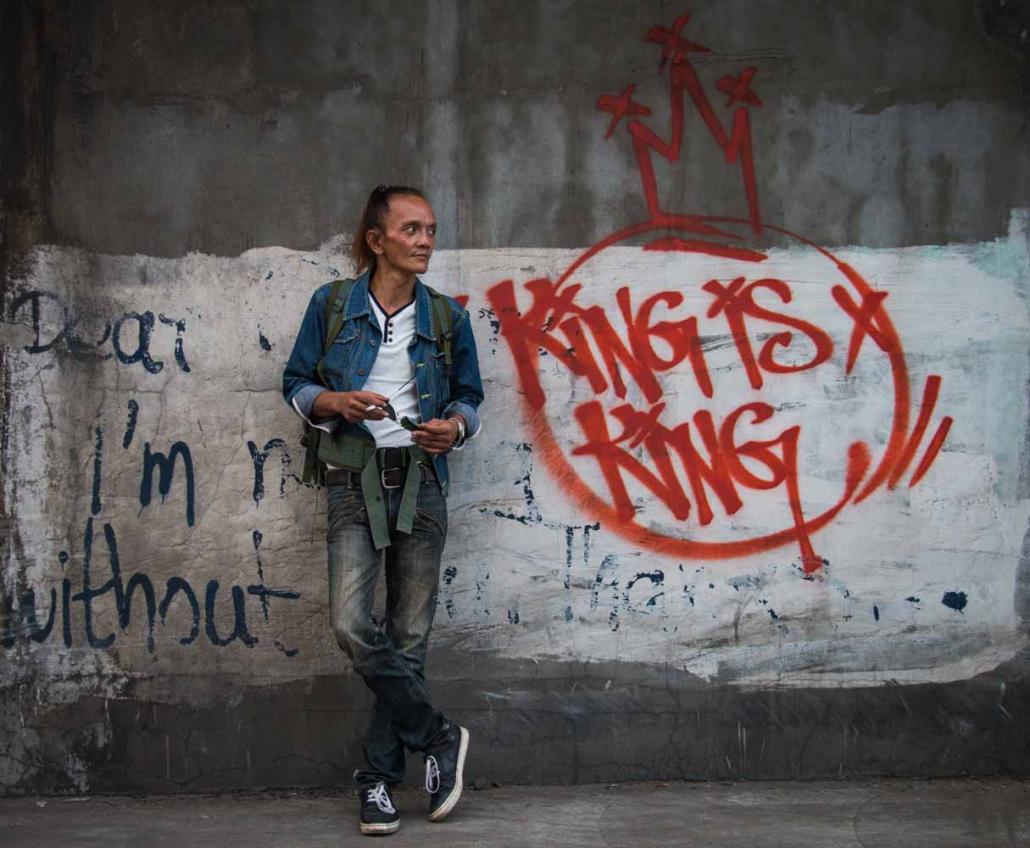

Ko Kyaw Htu is following the conversation closely. The gaunt, tattooed 44-year-old has been addicted to heroin since he was a teenager.

Each morning he diligently visits a small clinic to collect his dose of methadone for the day, or the week if he will be travelling, and then walks across the street to the office of the Myanmar Drug User’s Network, which he co-founded to provide education and resources for criminals such as himself.

Kyaw Htu is indeed a criminal, at least under Myanmar law, which can punish those who fail drug tests with compulsory rehabilitation, years in prison and an official “drug user” label.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Kyaw Htu failed two such tests in the 1990s and served two prison sentences. He narrowly dodged two more arrests, once by swallowing his tiny stash of heroin and bribing the police. By then he had already contracted HIV from sharing needles with other injecting users.

Bags of methamphetamine pills seized by the Thai narcotic police department are seen on display before being incinerated. Myanmar is considered a major source of methamphetamines in the region. (AFP)

On paper, his drug user status affords him treatment and resources to help deal with his addiction, and his HIV. In reality, it only paints a target on his back, he said.

“Registered, not registered, same situation. Registered drug users are arrested. Not registered drug users are arrested,” Kyaw Htu said. “It is only for show.”

The drug puzzle

Earlier this month, the second round of talks between the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the government was completed.

The discussions, which included input from the Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control, as well as law enforcement officials, social workers, healthcare professionals and INGOs, were held to discuss a new national drug policy – one aimed at combating trade and protecting victims.

A UNODC press release published on November 11 about the discussions said that a comprehensive national drug policy “fit for the times” is urgently required.

This is not only because of the limited results of the previous policy, but also because of the significant challenges Myanmar is facing, including a potential increase in poppy cultivation and heroin production, a rise in methamphetamine production, and higher drug use.

The statement noted that drug policy is not isolated, and cuts across public health, human rights, the needs of women and children, and sustainable development.

A third round of talks is scheduled between November 21 and 29 and the government and UNODC are plana-element file-full” daning to undertake a national drug use survey in 2017, the statement said.

Currently, efforts are hampered by a lack of data. There are no official statistics on drug use in Myanmar, according to UNODC, except for a Ministry of Health estimate on male injecting drug users that puts the number at 83,000 (of these around 7,000 are registered with methadone clinics.)

“Based on anecdotal reports, heroin and opium remain the primary drugs of use, followed by synthetic drugs, the use of which is perceived to be increasing,” said a UNODC statement released in February.

“The lack of recent data with regard to new trends and consequences of drug use, in particular of methamphetamine, makes it challenging to target strategies and interventions to the individuals, groups and communities in need of support.”

In simple terms: Myanmar has only a rough sketch of its drug problem, which makes it even more difficult to solve.

There is at least more data about the origin of Myanmar’s drugs. Most of the country’s heroin and opium are grown in Shan State. Myanmar is Southeast Asia’s top producer of opium, and the world’s second largest after Afghanistan.

The war on drugs is a paradoxical task for the Myanmar Police Force and the CCDAC. Poppy is often grown in remote areas controlled by armed ethnic groups or militias where incursions by the military or the police would threaten peace agreements.

Amphetamine production, on the other hand, is not geographically bound and producers can move their laboratories to evade police.

The upshot is that police have neither the funds nor the manpower to effectively target producers at the source or play cat-and-mouse with distributors, s coordinator U Tun Nay Soe.

“Look at the capacity of Myanmar police. How can they check every car? They don’t even have sniffing dogs. Forget about scanners,” Tun Nay Soe said. “Often police can only wait for the drugs to come to the city. But, for me, if you’ city, it’s already too late.”

These issues could at least partly explain why Myanmar’s drug laws, especially the harsh 1993 Narcotic Drugs and P, put pressure on individual users and street dealers.

Being caught under the influence of narcotics can result in a jail term of between three and five years, with another six months for the possession of drug-related paraphernalia.

Distribution and possession carries a heftier sentence: five to 10 years in jail, even for small amounts of

Harsh laws for drug use do not really solve anything, Tun Nay Soe said. “If you are arresting someone with 200 pills, 300 pills, what are you getting out of it? It’s a big expense for the government and prisons become overcrowded.”

Perhaps the most controversial component of Myanmar’s drug policy is the notorigistry, which rather than combatting widespread addiction only makes the situation worse, said Ms Ernestien Jensema, a social anthropologist working with the Drugs and Democracy Program of the Transnational Institute, a think-tank based in Amsterdam.

On paper, “drug user” is a healthcare status and even addicts who have never been arrested may voluntarily register.

In practice, it is a kind of ” hanging over the heads of users, allowing police to keep tabs on them and increasing their chances of time in prison, where they may or may not receive treatment.

“Drug users need to register to be able to enter services. Apart from mandatory registration, a lot of users are hesitant to register because of the stigma that comes with being a habitual drug user. It’s a criminal offence,” Jensema said. “The policy is still very much at the moment focused on repression.”

The policy makes users less likely to seek available help resources, making it harder for them to break their habit. Rather than suppress demand for drugs, it builds it, argued Jensema.

Reducing harm

Starting in October, the CCDAC launched a series of meetings with UNODC, TNI and other Myanmar and international organisations to discuss a new national drug policy.

“There is a need to have an enabling environment that involves law enforcement and the judiciary that makes access to drug treatment better,” said Mr Olivier Lermet, UNODC regional adviser. “We are pushing for a more balanced approach to drug control.”

UNODC and TNI both advocate the “harm reduction” philosophy, in which drug abuse is treated as a public health issue rather than a law enforcement matter.

Under this approach, ending harsh penalties for drug use and possession would almost go without saying. Lermet said that mandatory registration should be ended and treatment should always be voluntary. “We do not support the compulsory drug treatment centres because they are not effective. The relapse rate is very high,” he said.

Indeed, UNODC, TNI and other INGOs also suggest decriminalising drug use entirely. Law enforcement should focus exclusively on investigating drug producers and suppliers. Even street dealers should be treated leniently, given that many only sell to support their own habits, Lermet said.

“Drug use is a chronic and relapsing condition, exactly like diabetes,” Lermet said. “We have to separate crime that may be associated with drug use, and drug use itself.”

He said it was important for policymakers to understand the nuances of narcotics addiction. Heroin causes a powerful, physical addiction that may require a lengthy regimen of methadone treatment to wean users off the narcotic. Only one in 10 amphetamine users, on the other hand, require clinical treatment.

“Ninety percent of [amphetamine users] are best handled with voluntary, community-based treatment. Those people just need to be prevented from entering a problematic drug use,” said Lermet, who supports the establishment of neighbourhood counselling centres and education and awareness programs, and introducing the World Health Organization’s Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test.

Life with drugs

When it comes to understanding or sympathising with the daily struggle of drug users, Kyaw Htu has little confidence in his government.

“They cooperate with other organisations, other INGOs, other technical organisations, [but] they don’t know about the drug user behaviour and drug user community,” Kyaw Htu said. “They cannot prepare for or support what they don’t know about.”

He said he has seen officials talk this way before. President U Thein Sein supported a harm reduction approach to drug use, which included working with international health organisations to distribute clean needles for exchange programs, as well as condoms, to help prevent the spread of HIV, and relaxing the ban on drug paraphernalia.

Yet many police were either unknowing or uncaring of the new guidelines. They continued to harass registered drug users and patrol areas with clinics and resource centres to bolster their arrest records.

Even the concept of a drug dealer is more complicated that it might seem. Most street dealers scrape by with just enough profit to support their own habit, he said.

Kyaw Htu displayed a batch of clean needles, condoms and alcohol swabs supplied for free by the Burnet Institute, a public health NGO based in Melbourne, Australia. He said that even today he has to explain what they are for to the police who routinely visit his office.

“Some people cannot explain [why they have] their syringe, and they go to the jail,” he said.

Ko Kyaw Htu, 44, co-founded the Myanmar Drug User’s Network to provide education and resources to addicts. He began taking heroin as a teenager but now receives a daily does of methadone. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

Kyaw Htu knows other users who would never seek such supplies out of fear of being labelled a criminal and moral degenerate.

“Communities don’t know about harm reduction services,” he said. “They know a lot of drug users get the needles, and they are afraid. They are afraid the young people will learn about the drugs.”

If Kyaw Htu had access to education and resources when he was young, he might not have contracted HIV, or slipped so far into addiction. He might not have spent his best years in and out of jail.

When Kyaw Htu recalls his time as a user, he doesn’t seem to regard himself as a degenerate or dangerous criminal. He just needed a fix.

Top photo: A drug user heats and inhales crushed methamphetamine pills. (Theint Mon Soe — J / Frontier)