Last month, parliament concluded its last session before the election. It was an exciting time for the whole nation. Well, except for those who have lost track of what was going on. This no-shame introduction will get you up to speed.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

This story begins in 2008, when Myanmar adopted a new constitution that prescribed its first functioning legislature since 1988. Although the 2010 election was marred by allegations of foul play, it resulted in Myanmar’s first independent lawmakers in half a century.

On the national level, they compose the Assembly of the Union, or Pyidaungsu Hluttaw. (Hluttaw means “parliament” or “assembly.”) Three quarters of its MPs are elected representatives, and the remaining are appointed by the military.

The Assembly of the Union is made of two bodies: the House of Nationalities (Amyotha Hluttaw) and the House of Representatives (Pythu Hluttaw).

The House of Nationalities, or Upper House, has 168 seats elected evenly by state and district, regardless of population size. The House of Representatives, or Lower House, has 330 seats, one for each township. Each of these houses has its own committees, bylaws and leadership—a member-elected speaker and deputy speaker.

These houses debate and vote on proposed laws during sessions scheduled by the Speaker of the Union (a role traded off between the Lower House speaker and Upper House speaker).

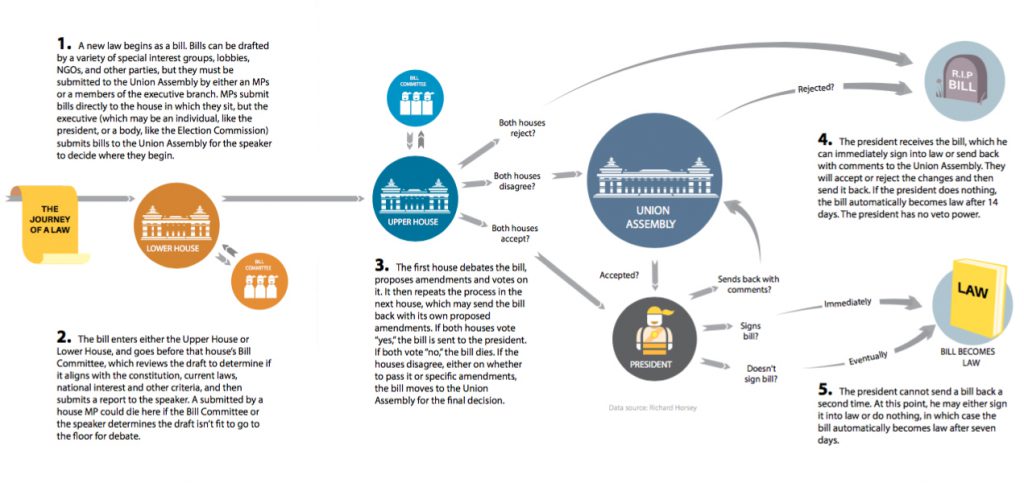

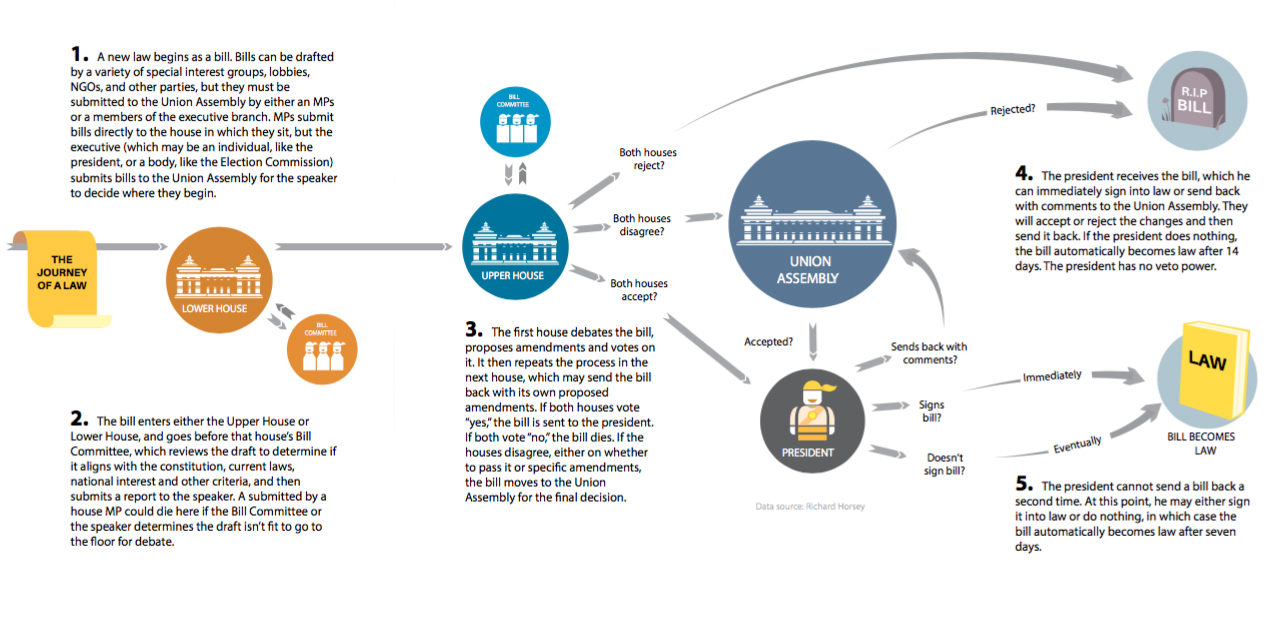

A new bill’s journey (detailed on the next page) is long and thorough. It must be debated and voted on in both houses, and possibly the whole Union Assembly if the two disagree, before it is sent to the president to be signed into law.

The president can send a law back to parliaments with comments, but he has no veto. On paper, there is nothing the executive branch can do to stop a bill becoming law if parliament sets its mind to it. Veto power resides with the military bloc, which this year was forced to use its veto to thwart constitutional amendments that would have reduced its influence.

Myanmar Lawmaking 101

A lively bunch

So how has this legislature been in its first five years? Apparently, a word of choice is “vibrant.”

A briefing from the International Crisis Group said the Union Assembly “has turned out to be far more vibrant and influential than expected.”

Likewise, a 2013 report in The Diplomat declared: “The country now has a vibrant, independent legislature.”

Prominent political analyst Richard Horsey, in a report for the Conflict Prevention and Peace Forum wrote: “The legislatures have been unexpectedly vibrant bodies, having serious and very frank debates, holding the executive to account, and often eschewing party-political perspectives in favour of what they see as the national interest.”

It seems the real fear wasn’t that the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw would be incompetent, just dull. Yet it has proved to be more than a rubber stamp, made especially clear in recent months as Lower House speaker U Shwe Mann, unseated as USDP leader, uses his sway in parliament to go toe-to-toe with both President Thein Sein and the military.

Yet others worry the freshman lawmakers aren’t living up to their potential.

“They are missing a real opportunity to be a check on the power of the executive,” said Vani Sathisan, legal advisor for the International Commission of Jurists, a civil society organization.

Most bills are still submitted by members of the executive, not MPs. Some of these have been put to intense debate and public scrutiny, yet others, Sathisan argues, are quietly ushered through the system without entering the public conversation and with little or no amendments.

Meanwhile, Myanmar’s law book remains a century-old patchwork of vague and out-dated edicts. It often serves as a sort of encyclopaedia of excuses to strip workers, journalists, activists and political opponents of their rights. Lawmakers face an almost crippling backlog of desperately needed reforms.

Yet, said Sathisan: “Vague laws are not being reformed and not being repealed, while critical pieces of legislation that could preserve the rights of ordinary citizens are being swept under the rug or delayed for unclear reasons.”

She mentions the Myanmar Investment Law and the updated Myanmar Companies Act, which would overhaul business in Myanmar. They remained stuck in the works when the last session adjourned, while the four “race and religion laws,” backed by Buddhist hardliners and drafted by the nationalist monk Ma Ba Tha movement, but roundly condemned by human rights groups (including the ICJ) as oppressive to minorities and women, had a comparatively easy journey through parliament in the latest session.

“These laws that are being passed are just entrenching the government’s power to harass ordinary citizens,” she said.

It may not be that many MPs are tools of the executive agenda; they are just inexperienced and underequipped. The majority of new bills are still submitted by the executive branch, guided by teams of legal and policy experts. MPs, on the other hand, aren’t even provided office space in the parliamentary complex.

Horsey writes: “Without professional advisers and research staff, they are left to navigate unfamiliar issues on their own. Even if they are reform-minded and well-intentioned, as many are, the set of personal experiences that they have to draw on are not the most relevant to the new realities in Myanmar.”

Sathisan says lawmakers could turn to simple transparency to even the scales, bringing civil society organizations, advocacy groups and the general public into the conversation.

Yet “basic up-to-date information is very hard to obtain,” writes Horsey. Some bills are in the public conversation through the entire process; more are shrouded in smoke and mirrors until they are already in the books.

Thus, Myanmar’s legislature is a bit like a new car with a teenage driver behind the wheel. Sathisan hopes its MPs will mature with time. Indeed, the parliament complex recently opened a new research center as an intellectual resource for lawmakers. She implores whoever wins out in the next election to continue to battle for Myanmar’s human rights obligations, the interests of their constituencies, and their own autonomy.

“I am cautiously optimistic,” she said.