Five performers of a traditional form of satirical theatre are languishing in jail, thanks to a criminal complaint from the Tatmadaw, whose attitude to Thangyat differs sharply to rulers in Myanmar’s past.

By YE MON | FRONTIER

PRIME MINISTER U Nu, a former anti-colonial dissident who led Burma in the early years of independence, was once at the receiving end of a biting satirical skit by a group performing the traditional art of thangyat, according to veteran poet Maung Thway Thit.

“The people thought the troupe would be arrested after U Nu invited them on stage to perform. Their verse contained very strong criticism,” Maung Thway Thit said. “But U Nu gave them a prize instead. There has never since been another leader like him.”

The Tatmadaw’s recent decision to initiate legal action against members of a thangyat troupe in Yangon has shown that Myanmar’s military, which retains considerable governing powers as well as influence over the judiciary, is incapable of emulating the tolerance of U Nu, or even of the pre-colonial Bamar kings.

With five young performers held in Yangon’s Insein Prison, facing a trial that could result in prison sentences, the National League for Democracy government meanwhile has been unwilling to stand up for a traditional form of expressing free, critical speech.

Censoring witty verse

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Thangyat is a form of popular theatre that combines poetry, music and dance. It was first performed during the New Year festival of Thingyan under the patronage of the Bamar kings, before colonisation by the British in the 19th century. The form has always had a subversive edge, satirising social conditions in the country and the rule and behaviour of governing authorities. The king and his top ministers were not spared, despite being absolute rulers.

Like other traditional art forms, thangyat went into decline during the colonial era, but was preserved by some dedicated artists and underwent a revival after independence in 1948. Troupes performed on the ceremonial stages, called mandats, that are erected in public areas every Thingyan in mid April, and entertained people with witty verse that spoke directly to their troubles and grievances.

Under the dictatorship of General Ne Win, who seized power in 1962, thangyat performances were subject to the same censorship as other creative forms. The words to be used in a performance had to be approved beforehand by a censor board, which frustrated thangyat’s purpose of satirising the powerful through verse.

The military junta that took power in another coup in 1988 banned thangyat outright. Underground performances continued, and the junta turned a blind eye to some of these, for instance one led by actor and social activist U Kyaw Thu outside the Yangon home of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi when she was under house arrest.

The ban was maintained by the Union Solidarity and Development Party government until 2013, two years after it took office, when it was permitted albeit with the prior censorship of the verse, similar to the Ne Win era. Uncensored thangyat was cautiously revived after the NLD government took office in 2016, though it re-introduced censorship the following year.

Retired performer Maung Hnin Lwin proudly recalls his thangyat troupe, which was active in the late 1970s and early 80s. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Arrest, perform, release

Maung Hnin Lwin, a leading performer with the Dae Doe thangyat troupe from 1976 to 1983, said that during the Ne Win era police would only briefly detain the groups if they did not follow censorship rules, giving opportunity for criticism.

“The groups would be inspected by the police and then given a warning and released. They weren’t detained in jail,” Maung Hnin Lwin told Frontier.

“At that time, people could only criticise the government through thangyat performances during Thingyan,” he said. “The government was frightened by it.”

Maung Hnin Lwin said that after the post-1988 ban on thangyat, the art form was kept alive by Myanmar living outside the country, including political exiles.

Poet Maung Thway Thit said there was a strong sense of solidarity among thangyat troupes from independence to 1988 and if performers were detained, groups would assemble outside the police station where they were being held and give performances.

“The police would eventually release people [without charges],” he said, adding that he had never heard of thangyat groups being sent to jail in the past.

The decision by the USDP government to continue censoring thangyat was criticised at the time by members of the NLD, then in opposition. However, during Thingyan this year, like the previous year, thangyat troupes were ordered to submit the words in their performances to censorship. The authorities also pressured venues not to host troupes that refused to comply with the order.

NLD spokesperson Dr Myo Nyunt defended the censorship decision, saying it was a “temporary” measure. “We worry that unnecessary things will happen due to the thangyat,” he told Reuters news agency. “We always prioritise and are working on freedom of speech and freedom of expression.”

Forbearance’s limit

Maung Thway Thit expressed disappointment that censorship was occurring under the government of State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The NLD government should stand for freedom of expression, he said.

His comments came after the Tatmadaw filed criminal complaints against multiple members of a youth thangyat group in Yangon called Daung Doh Myo Sat, which means Peacock Generation, for allegedly defaming the military in their Thingyan performance, which they did on the street in order to circumvent the censorship order.

On April 15, Lieutenant-Colonel Than Tun Myint from Yangon Command lodged the complaint at Mayangone Township Court against Ko Zeyar Lwin, Ko Paing Ye Thu, Ma Kay Khine Tun, Ko Phoe Thar and Ko Paing Phyo Min under section 505(a) of the Penal Code. The five have been held in Insein Prison since a court appearance on April 22.

Section 505(a) of the colonial-era code says that anyone making, publishing or circulating any statement, rumour or report with the intention of causing a member of the Defence Services to mutiny or otherwise disregard or fail in their duty is liable to a maximum penalty of two years’ jail and a fine.

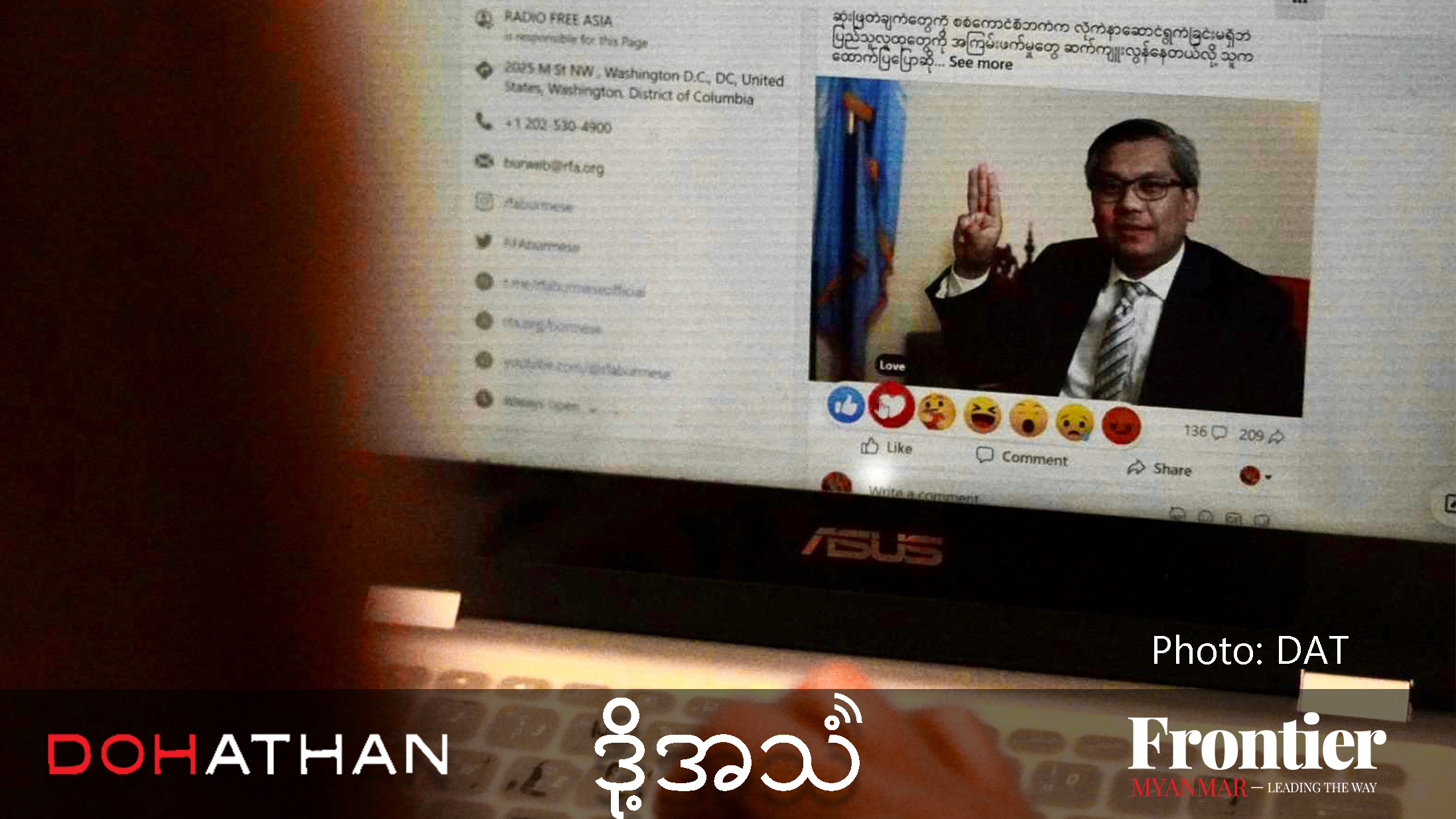

Than Tun Myint filed another complaint, also on April 15, at Mayangone Township police station against four members of the troupe for online defamation under section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Act, because the performance was live-streamed on Facebook. These were Zeyar Lwin, Paing Ye Thu and Paing Phyo Min, who also face the Penal Code charge, but included another, Ma Su Yadanar Myint. Those accused of online defamation have yet to be brought before a court.

The Peacock Generation troupe’s verse satirised the Tatmadaw and its continued role in the nation’s parliament, the Tatmadaw-drafted 2008 Constitution, the education system and the plight of people displaced by civil conflict. Some skits saw the performers wear imitations of Tatmadaw uniforms.

“There are senior military officers who covet power and money,” said one of the lines.

NLD information officer U Aung Shin told Frontier that he opposes the censorship of thangyat shows and that the Tatmadaw should not have filed criminal complaints against members of the Peacock Generation troupe.

“I don’t know why the government is still continuing censorship; in my opinion, there should be no censorship,” he told Frontier.

Brigadier General Zaw Min Tun, secretary of Tatmadaw True News Information Team, told Frontier that members of the public would understand the Tatmadaw’s motives if they were personally subjected to criticism by a thangyat group. “The people would also want to sue them,” he said. “Forbearance has a limit.”

Former thangyat performer Maung Hnin Lwin (left) and veteran poet Maung Thway Thit reminisce about dodging censorship under the dictatorship of General Ne Win. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

‘Not a crime’

Su Yadanar Myint told Frontier that the troupe did not blame the NLD government for their predicament, but were disappointed that the NLD had not spoken up for them.

“There are two governments in Myanmar,” she said. “Everyone sees that the military is also a government. They [the Tatmadaw] filed a lawsuit against us and other activists but the NLD government hasn’t commented, which is a surprise for us.”

However, although the Tatmadaw can file criminal complaints, they need to be prosecuted by government law officers who answer to the NLD-appointed Union Attorney General. Under the colonial-era Code of Criminal Procedure, law officers have the discretion not to proceed with cases if they believe they lack enough evidence or are not in the public interest. Cases can be later withdrawn for the same reasons. However, law officers rarely exercise this discretion.

Lawyer U Khin Maung Zaw, who defended jailed Reuters journalists Ko Wa Lone and Ko Kyaw Soe Oo, said the law officers have the power to scrutinise and reject criminal complaints if they lack legal merit.

“Law officers are accepting [the military’s] complaints. So, we can say that the government is also involved in the threat to freedom of expression.” Khin Maung Zaw said. “Thangyat performances are not a crime.”

Maung Thway Thit said he was not aware of any thangyat performers being held in prison under the military regime and the USDP government. The first criminal complaint against a thangyat group was being prosecuted under a government elected by the people, he said.

“It should not be happening under the NLD government. The government should say something,” he said.

However, prominent lawyer U Robert San Aung recalled the case of two poets being sentenced to seven-year prison terms for a thangyat performance in 1975. The Peacock Generation five were the first thangyat performers to be detained in prison for 44 years, he told Frontier.

Robert San Aung also expressed concern that a new generation of thangyat performers would not emerge if the Tatmadaw and the government did not respect freedom of expression.

Maung Thway Thit said he is “very concerned” that thangyat groups would disappear.

Su Yadanar Myint, however, was defiant, saying the Peacock Generation would continue to perform thangyat without fear at future Thingyan festivals and expressing confidence that a new generation of performers would emerge to continue the tradition.

“I don’t think that the new generation has fear,” she said. “I want to tell them, please continue to perform thangyat with dedication and without fear.”