Open to the public but almost forgotten, Yangon’s towering and lavish National Drug Elimination Museum is a living relic of military propaganda.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE

AS USUAL, Police Major Nyi Nyi Lynn’s anti-drug museum is almost empty. His footsteps echo through the dim hallways lined with portraits of retired generals, dioramas of British and Burmese soldiers bayonetting one another, and a replica poppy plant, two metres tall.

One display features a towering map of the country and promises a drug-free Myanmar by 2015.

“The plan has been extended five years,” Nyi Nyi Lynn said matter-of-factly, as if eradicating the poppy and methamphetamine trade were no different than a new highway project.

nswks-11.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But the major has been fighting drugs in Myanmar for 35 years, and he is patient. He formerly served as a tax officer in the Drug Enforcement Division of the Ministry of Home Affairs, and claimed he took on so many extra duties that the stress eventually gave him cancer.

“My stomach, my spleen, my pancreas, I gave these for my country,” he said.

After recovering, he was made chief of the ministry’s new National Drug Elimination Museum, which – as skirmishes raged in border areas and Senior General Than Shwe’s Myanmar found itself on international drug trafficking watch lists – would be a tangible symbol of the government’s devotion to peace and development.

The ribbon was cut on June 26, 2001, the International Day Against Drug Abuse, as police officers ceremonially incinerated the year’s drug seizures.

nswks-34.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

Now the windows of the towering white building in Yangon’s Kamaryut Township are dark. The great fountain in the sprawling compound is dry and rusting, and the beautiful Japanese grass is overgrown with weeds. Inside the vast atrium, a mannequin farmer leads his buffalo through a field of blooming poppy. He has been carefully dusted, but the lights are off, and the artificial stream that runs through his field hasn’t been filled for years.

“All displays are electronic, but they were turned off day by day,” Nyi Nyi Lynn said, arriving at an interactive display that invites visitors to help police incinerate a pile of drugs. Embarrassed, Nyi Nyi Lynn spends several minutes flipping switches on wall panels until it activates.

nswks-61.jpg

Nyi Nyi Lynn, the manager of Yangon’s National Drug Elimination Museum. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

Nyi Nyi Lynn and his team do their best to maintain the place, but other than the wages for a skeleton staff, the ministry has left the museum to fend for itself.

Most visitors are students on field trips, who don’t pay an entry fee, and the occasional tourist after reading about the “insight into the strangeness and paranoia that has pervaded Burmese society for decades,” as Vice described it, or simply a “brutalist eyesore,” according to the Atlantic.

nswks-32.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

The museum isn’t technically “brutalist” (the architecture more resembles the stately, white, government complexes in Nay Pyi Taw), but the term captures the sentiment of the visitors who poke fun at the bizarre testament of military propaganda and ask themselves, in the era of the National League for Democracy, why the museum is still open?

Nyi Nyi Lynn has an answer.

“This government, they don’t even know the drug museum is still in Yangon,” he said, adding, “But everybody local is interested in our museum.”

“Everybody local” includes big-name developers who Nyi Nyi Lynn says still covet the prime museum site, which borders the Junction Square shopping mall. Nyi Nyi Lynn reckons the site is worth K700,000 (about US$530) a square foot.

nswks-29.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

He said the museum spent the last decade only a handshake away from being sold to one of the country’s prominent business families, as was the site for Junction Square. Both plots were once Yangon’s largest cemetery.

In a way, Nay Pyi Taw was the drug museum’s saving grace: After it became the capital in November 2005 there were only two big museums left in Yangon (the other being the National Museum) and officials needed something to show foreign dignitaries visiting the city. Among them was United Nations Secretary-General Mr Kofi Annan.

Now the museum is safer than ever. The NLD government is unlikely to risk accusations of favouritism by selling the land to a private developer, and the Ministry of Home Affairs has little reason to bother with its obscure passion project from 2001.

nswks-12.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

The Drug Elimination Museum more or less holds its fate in its own hands, and Nyi Nyi Lynn isn’t changing anything.

He believes in his museum. “The main ambition is that people and students visit our museum and gain knowledge that drugs are dangerous,” he said in the same sincere, matter-of-fact tone.

That Myanmar hasn’t succeeded in ending its drug trade makes his museum all the more relevant, and he has kept everything exactly as it has been since the ribbon was cut (except for photos featuring former Military Intelligence chief General Khin Nyunt, which were removed after he was arrested during a power struggle in 2004).

nswks-73.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

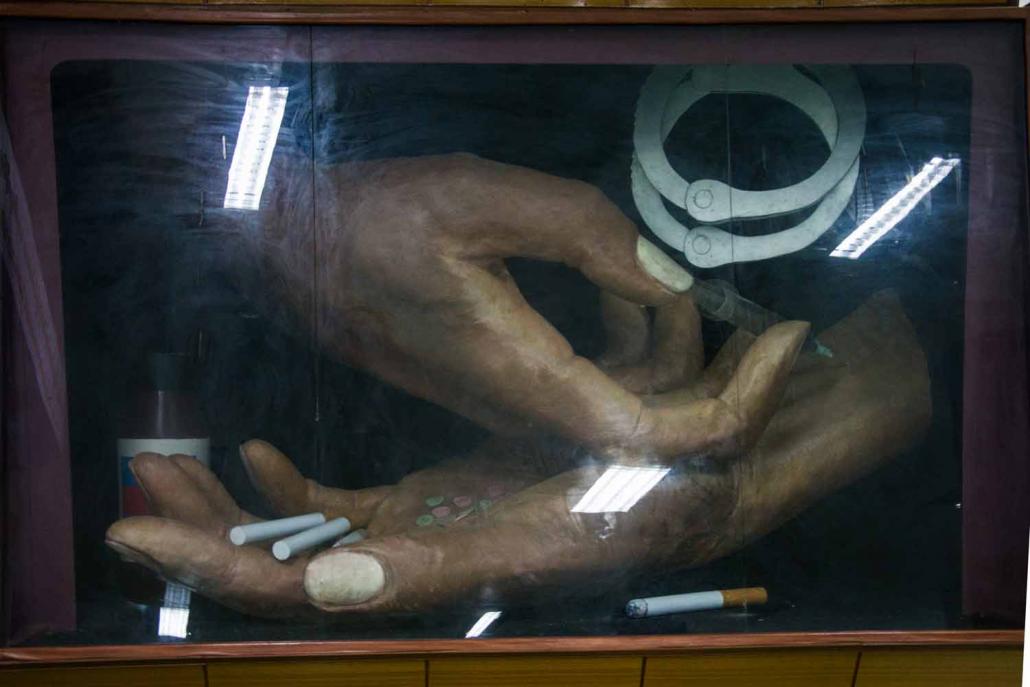

The exhibits (originally designed by Daw Nu Myat San of the Ministry of Culture, who also designed the National Museum) depict the history of Myanmar from the time of Portuguese colonists and the British opium wars. They cast drugs as a great, foreign antagonist that has plagued the country, from individual addicts to the unruly rebels ensnared in its trade.

On the top floor, educational displays about heroin and methamphetamine are juxtaposed with murals of thriving crops, models of bridges and photos of generals shaking hands with ethnic leaders overjoyed to be returning to the “legal fold”.

It is a narrative free of human rights abuses, corruption and greed, and it has been almost perfectly preserved in a bureaucratic buddle at the corner of Hanthawaddy and Kyun Taw roads. You can see it for K4,000.

Nyi Nyi Lynn will retire next year. He doesn’t know who will replace him after he leaves, but he is confident they will carry on the good work.