A dwindling number of old men who fought with the British in World War Two are living contradictions to the myth that Myanmar’s people united against colonial rule.

By BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

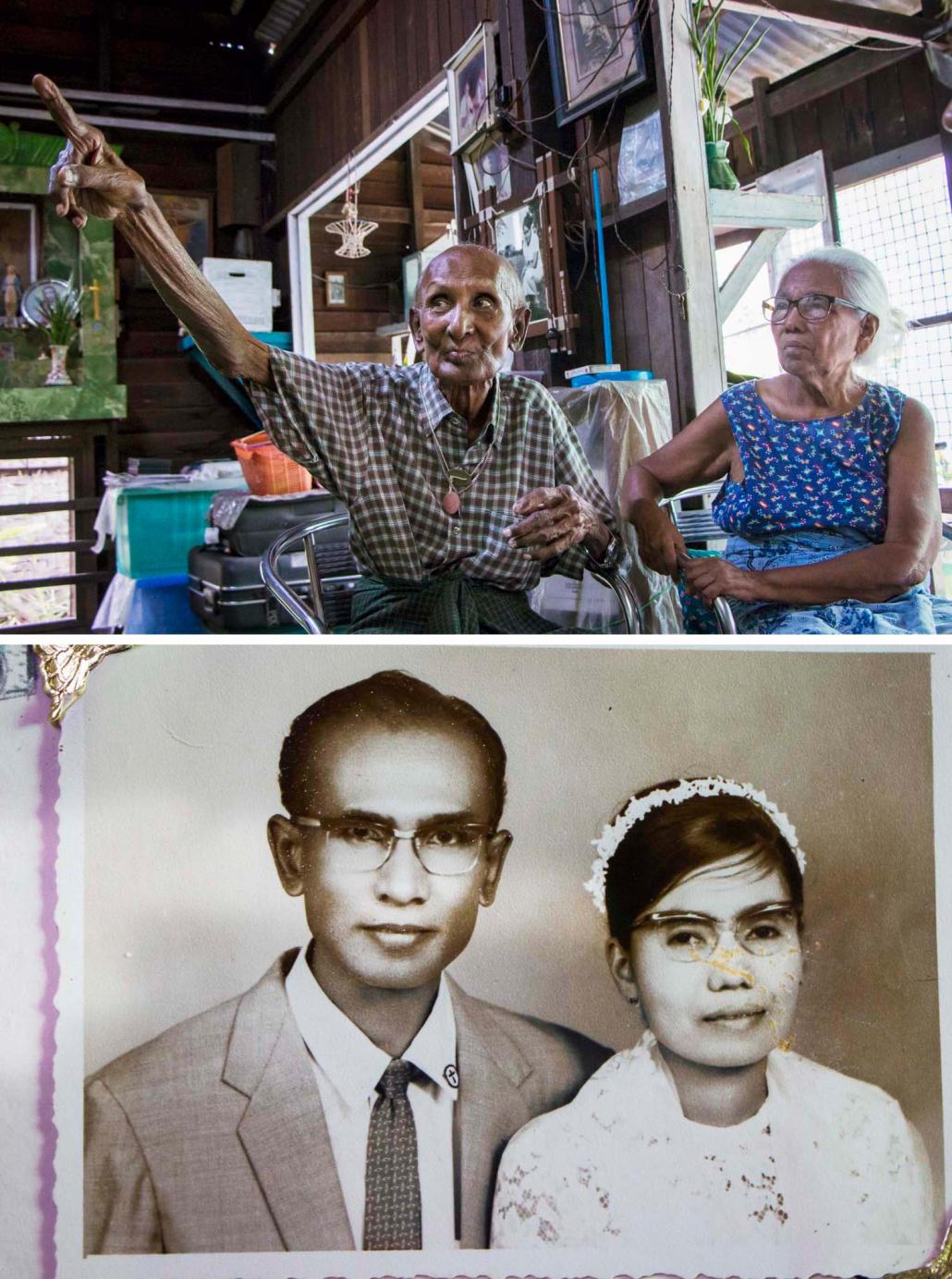

MR DAVID Daniel lives with his wife Amelia among crucifixes and portraits of a young Queen Elizabeth II in a simple wooden bungalow in eastern Yangon’s Thingangyun Township. It’s the only house of its kind left on the quiet residential street; the other homeowners had agreed for their houses to be demolished in exchange for boxy flats in the concrete high-rises that construction companies built in their place.

David and Amelia had refused such a deal. The creaking bungalow and its walls cluttered with faded prints and photographs was all that connected them to a vanished world.

David, a wiry, smooth-headed 95-year-old, was born in Maymyo, now Pyin Oo Lwin, to an Anglo-Indian father and Burman mother when Myanmar, then Burma, was ruled by Britain as part of its Indian empire. His 85-year-old wife, Amelia, who keeps a full head of silver hair and shares David’s mission-school English diction, grew up across the Yangon River in rural Twante Township as one of the few Burmans to be brought up Christian. The two met in Rangoon after Burma became independent in 1948, while Amelia was a matron at St John’s Convent School (now Basic Education High School 2 Latha) and David was working at the office of the Controller of Military Accounts.

“She thought I was a big shot!” he told me during an interview at his house on a hot afternoon in September.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

David chuckled, but there was a sad irony to his statement. Growing up in colonial Burma as a Christian with English heritage, David had advantages that other Burmese didn’t, but after independence, this flipped. With the government and military led by firebrands of the anti-colonial movement, a man who venerated Britain and its empire found himself adrift, his privileges worth little.

“I have so much respect for the Queen and her family,” he said, gesturing towards a photograph of the British royal family from the 1970s that included Crown Prince Charles as a young, uniformed naval officer. “I pray for them all the time.”

I asked how he felt when the British left Burma in January 1948 – a time of jubilation for the country’s majority Burmans, or Bamar, tinged only by the tragic assassination of independence hero Bogyoke Aung San six months earlier.

“I was very sad,” he said. “Under the British, there was justice.”

It’s a view with which the Myanmar government and many in the public would vigorously disagree. At school, children learn about the cruelty of the British, who annexed Burma in three wars in the 19th century, culminating in the capture of the royal capital Mandalay in 1885 and the banishing of the last king, Thibaw, to exile in India. Military rulers since independence have blamed long-running ethnic rebellions against the central government on the “divide and rule” tactics of British rule, and Britain’s enabling of mass migration from India is cited to justify exclusionary laws and policies on citizenship, such as those that make Rohingya Muslims stateless.

Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing rarely misses an opportunity to bring up British misrule. On an official visit to Europe, in November 2016, he told a meeting of the European Union Military Committee in Brussels how British occupation had resulted in “people from Bengal” migrating and settling in what is now Rakhine State, sowing the seeds of the current Rohingya crisis.

tz-2306-2318.jpg

Mr David Daniel proudly recounts his wartime service while sat next to his wife Amelia in their home in Yangon’s Thingangyun Township (top) and a photo of the couple on their wedding day hangs in their house. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

‘Unfinished business’

Speaking to the press in Nay Pyi Taw in September 2017 about an army crackdown on Rohingya militants that sent more than 700,000 Rohingya into neighbouring Bangladesh, Min Aung Hlaing called it “unfinished business” from World War Two. He was referring to the vicious fighting in Rakhine, then Arakan Division, between Muslim volunteers armed by the British and Buddhists who sided with the Japanese.

You needn’t agree with the senior general’s diagnosis of present-day conflict to agree that, throughout the country, the “business” of World War Two remains in many ways unfinished. The war pitted Burma’s ethnic groups against each other, with the Bamar and Rakhine initially aiding the Japanese conquest and hill-based communities such as the Karen, Kachin and Chin fighting to maintain and then restore British rule.

The Karen revolt, which began 70 years ago, was spearheaded by Karen leaders who had fought with the British but felt their aspirations for autonomy were short-changed by Britain’s independence settlement with Aung San. Karen soldiers mutinied and came within miles of taking Rangoon.

David Daniel was at the other side of the front line in May 1949, repelling the Karen forces at the town of Insein, just north of Rangoon, as a soldier of the post-independence Burma Army. The fighting was “tough”, he said. “The Karen were very strong, and well armed.”

But by that time, David was experienced in brutal combat. On one wall of his living room, below a picture of the British queen in a bejewelled crown, was a faded print of a man wearing a bushy moustache and khaki uniform, binoculars hung around his neck. “General Slim,” he said. “My commander.”

David was part of Lieutenant-General William Slim’s 14th Army, a force filled by soldiers from across Britain’s global empire that retook Burma from the Japanese in World War Two in a long march from the mountains of northeastern India, down through the Chindwin and Irrawaddy river valleys to Rangoon. David was there when Mandalay and the towns of central Burma were retaken, and said the fighting was “terrible”. “Even now, I have nightmares,” he said.

Despite the lingering trauma, this violent past was memorialised all around David and Amelia’s bungalow. Besides the prints of Slim and other British commanders, the walls bore the insignia of British army regiments, mementoes from the 1944 Battle of Kohima, when British forces broke the Japanese advance into northeastern India, and a photograph of David as a young captain, in a beret and dark glasses.

But the pride he still took in his wartime service was made clearest by the army ID tag that hung from his neck. I asked him why, seven decades on, he still wore the thin metal disk bearing his name and a serial number relating to a vanished army. “Old soldiers never die,” he said.

tz-daniel1.jpg

A portrait of Mr David Daniel (top left) who still wears an army ID tag from World War Two around his neck. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Allies remembered

David’s service was unlikely ever to be recognised in a post-independence Burma led by men who fought on the other side of the war, with the Japanese, before Aung San sensed an Allied victory and switched sides, helping the British to chase out the “fascists” in 1945. But David was destined to be forgotten by the British, too. In British memory, the Southeast Asian theatre in World War Two has always been overshadowed by the defeat of the Nazis in Western Europe. Every British schoolchild learns about the D-Day landings in Normandy, but few learn of Kohima.

Because Burma opted out of the Commonwealth at independence and spent decades in isolation after a military coup in 1962, the country lacked the kind of ex-servicemen’s organisation that was formed in many Commonwealth countries, linking World War Two veterans to large British charities.

Despite the official neglect, David and Amelia now receive annual welfare grants from a small British charity, Help for Forgotten Allies, or H4FA. The charity has also met medical expenses for the couple, such as when Amelia needed an eye operation. David is one of about 100 World War Two veterans, along with more than 30 widows, who receive this help, H4FA founder Ms Sally McLean told me.

The charity, founded in 2007, has run mostly on private donations and the efforts of volunteer staff, though it now also channels money from the British government, which in November last year pledged £11.8 million pounds (US$14.6 million) in cash transfers to “pre-independence war veterans” of the British armed forces living in poverty in former British colonies.

McLean said that, though the grants are given to veterans “in recognition of their poverty”, they above all represent a “recognition of their service”, however belated.

She said support for the charity had risen on the back of a new documentary film, Forgotten Allies, which follows H4FA trustees on a trip to Myanmar, meeting veterans in Yangon and in the hills of Chin and Kayah states, and recounts the story of World War Two in the country. In the film, David Daniel is seen wearing his old uniform, pinned with medals, ready to attend a Remembrance Day event.

The British producer, Mr Alex Bescoby, said at the Myanmar premiere of the film in Yangon on September 7, “We were amazed at how little knowledge there was of the role these gentlemen played in this chapter in our shared history.”

“We feel very lucky that we caught some of the last whispers of this story before many of the gentlemen disappeared from our ranks,” he said. “No less than five [veterans] have passed on since we finished filming in December 2017.”

‘We didn’t know fear’

One member of the H4FA team tailed by the film crew, Mr Duncan Gilmour, visits mountainous Kayah State where his grandfather, Lieutenant-Colonel Edgar Peacock, recruited levies from villages to conduct highly effective guerrilla campaigns against the Japanese as part of Britain’s Special Operations Executive Force 136. Gilmour tells the camera of his continued surprise at the “loyalty” the veterans still feel towards the British, and the lack of resentment over their neglect. Several veterans greet H4FA trustees with the words, “We knew you’d come back.”

Saw Berny, who is also in the film, told me during a visit to his modest house in Yangon’s East Dagon Township in September of the time “Colonel Peacock came down in a parachute”. The 96-year old Karen man was a small, alert figure, squeezed into a wheelchair whose steel frame was rusting. Even with a hearing aid, he struggled to catch my questions, but his memories of serving under Peacock in 1945 were vivid.

He recalled how, armed with a Sten submachine gun or deputed to lay land mines, he had taken part in ambushes on Japanese columns that marched through the jungle or went by raft along the Salween River. He also participated in a raid on Kyaukkyi, a town now in Bago Region on the edge of the Karen hills. “We raided in a dawn attack,” he said. “The Japanese were badly defeated.”

Berny said the Japanese were “very cruel”. “They killed people for nothing,” he said. David Daniel had similar memories of Burma’s new invaders: “If you were caught, you were tortured,” he told me. But Berny said some of the abuses inflicted by the Japanese on Karen villagers were driven by desperation. “They were starving,” he said of the Japanese soldiers. “They didn’t have enough rations, so they looted.”

I asked Berny whether, as a young man facing a notoriously brutal enemy, he was able to cope with the fear. His answer surprised me. “We didn’t know fear at that time,” he said. “We were so happy when our commander told us, go and ambush here, go and ambush there.” He said the fighting was partly a relief from the desperate conditions of Japanese occupation, when army units requisitioned agricultural produce and communities were policed harshly. “We became miserable. It was hard to get our daily food, and we had to go far up into the hilly places. We couldn’t do anything. So when the British came, we were very glad to see them.”

Buoyed by an eagerness to fight, Berny and his fellow soldiers also overcame the privations of jungle warfare with traditional Karen know-how. When a period of bad weather meant British planes couldn’t drop their usual rations, “We killed some snakes and cooked them. Major Wilson joined us for the snake curry,” he said, referring to a British officer. Did Wilson enjoy the curry, I asked. “Yes!” Berny said.

7_tz-2219.jpg

Saw Berny joined other Karen volunteers in Britishled guerrilla campaigns against the Japanese. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

A myth of unity

The young Berny, unlike David Daniel, was not driven by a broad attachment to British rule. Asked how he felt when the British quit Burma less than three years after the war, he said he paid the event little regard: “At that time, we had no idea about politics. We didn’t know what our [Karen] leaders were doing with the Burmese and British high authorities. We were small. They wouldn’t listen to us.”

Nonetheless, he said his British officers were “very kind” and remembered Major Hugh Seagrim with particular fondness. Seagrim led a force of Karen volunteers, including Berny, during an earlier period in the Japanese occupation and was executed in Rangoon in September 1944 after surrendering himself to the Japanese to stop reprisals against the Karen. Berny said his brother Edward had earlier served under Seagrim in the Burma Rifles and that Seagrim instantly saw the family resemblance. When Berny joined his irregular force, Seagrim said, “You must know Edward.”

Historian Mr Philip Davies, who wrote a book largely about Seagrim, Lost Warriors, published in 2017, said close personal bonds – often helped by a shared Christian religion – were typical of the alliance between the British and upland communities like the Karen, Chin and Kachin during the war and colonial era in general. “An intense loyalty developed between the British officers and the men under their command,” he told me. “Seagrim clearly loved the Karen, and he was not alone.”

This raised expectations, particularly among the Karen, of future independence or protection by the British from Bamar domination. These were dashed when, soon afterwards, the British left Burma largely in Bamar hands. “Post-war, the Karen felt an incredible sense of betrayal,” Davies said. “They had fought alongside the British, who then handed over power to Aung San, who had fought with the Japanese.”

In Myanmar today, a myth persists that Myanmar’s different ethnic groups united to resist their colonial oppressors, and so restored a historic union of races that the British did their best to divide. The story is told in schoolrooms, where textbooks describe the British “splitting the blood”, but also in government broadcasts.

In a speech marking the 70th anniversary of independence on January 4, 2018, then-president U Htin Kyaw told the country, “We lost our sovereign kingdom in 1885 and became slaves of a conquered nation. To liberate ourselves from this life of slavery, all the ethnic national races, from the mountains to the plains, sacrificed their lives, blood and sweat to escape from slavery.”

It is understandable that a nation as diverse and fractious as Myanmar would promote a narrative of brotherhood and shared endeavour. But several ethnic groups have long memories that contradict this version of events. While men like Saw Berny and David Daniel remain with us, they embody an inconvenient truth that must be acknowledged if Myanmar’s peoples are to be truly reconciled.