After decades of military rule, the culture and mindset is stifling reform efforts, but tackling the problems will require huge political commitment and long-term investment.

By HENRICH DAHM | FRONTIER

Many of the government’s efforts to reform the country have been thwarted by a lethargic and inefficient bureaucracy. The bureaucracy must provide the backbone for any transformation, but decades of centralised military dictatorship have left public administration firmly under the Tatmadaw’s control. Reasserting civilian control and pushing government agencies to deliver breakthrough results is one of the government’s key challenges.

Waking up to the challenge

Many problems in the public sector stem from the Tatmadaw’s dominance of the country’s political and economic life. The military’s influence on public administration has created a mindset that government agencies should operate like well-oiled machines whose working parts fit together seamlessly to drive daily work. This mechanistic view prizes bureaucracy because it generates routine, repetition, orderly action, clear boundaries and an established hierarchy for oversight. All processes are designed in a precise, deliberate way to ensure that staff rely only on instructions from the top to execute tasks. These underlying rules reinforce the power of the Tatmadaw and have a crippling effect on reform efforts.

In recent years, it has become clear that the bureaucracy’s inflexible and slow processes limit the strategic options available to the government. Yet the government hasn’t really woken up to the challenge; it still wonders why many of its new policies and reforms do not have the intended results.

The government of U Thein Sein stressed the importance of “effective and efficient government” in its so-called “third wave” of reforms, but was better at announcing policies than implementing them. It quickly realised that such reforms would have little impact until well after the end of its term and instead continued to concentrate on policy reforms that could be enacted quickly.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The real question is how to do it. The military historian and theorist Captain B H Liddell Hart probably said it best: “The only thing harder than getting a new idea into the military mind is to get an old one out.” Many military leaders would agree that their organisations are highly resistant to change as a result of their size, complexity and culture.

If the system is designed to prevent change, then the forces at work in the system must be changed.

Governments and military organisations that thrive seek the attribute of agility: the power to be both dynamic and stable at the same time. This combination sounds paradoxical and many organisations struggle with it, mistakenly thinking they need only to become better, more flexible and more innovative.

Smartphones that have taken the world – not least Myanmar – by storm and changed the lives of millions exemplify the ability to be both dynamic and stable. This is the essence of true organisational agility: The hardware and operating system form a stable foundation; on top of it sits a dynamic application layer where users can add, update, modify and delete apps over time as requirements change and new capabilities develop.

In the same way, agile public-sector institutions can design their organisations with a backbone of stable elements – for example, a simple organisational structure or operating norms. These foundations, like a smartphone’s hardware and operating system, are engineered to endure. Agile institutions also have dynamic elements: organisational “apps” to plug in as new opportunities arise or unexpected challenges shift the norms. Typically, these task forces, projects, and new governance committees exist outside the system to be able to adapt rapidly to changing needs in an agile way, which combines stability with a dynamic capability.

Unwind the massive, self-imposed complexity

Myanmar’s public sector is extremely complex, involving nearly one million people who work on a wide range of activities from public service delivery to staffing different industries. Most ministries are Dickensian, with piles of paper stacked up on desks. There is a lack of co-ordination between departments within a single ministry, let alone between ministries.

Three main internal forces of resistance make it hard for Myanmar’s public-sector agencies to become more agile.

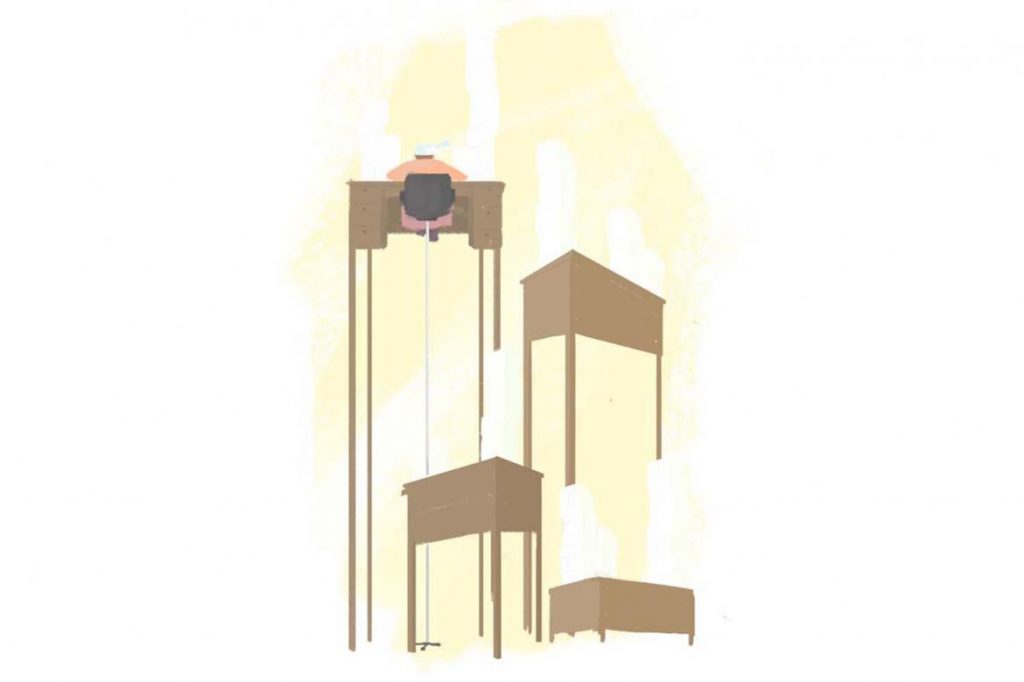

The current system from the union to township levels has a massive number of controls in place, creating a system that struggles under its own weight. In addition, layers of management and functional silos force decisions up to ever higher levels of command. This amplifies longstanding tendencies to concentrate power in a few hands and delegate little. As a result, the governance system is highly centralised, with most decisions still being made in Nay Pyi Taw. For example, within each ministry, often only the minister, permanent secretary or director generals have the authority to integrate across departments and work with other ministries. In organizations as vast as a ministry, that is an impossible burden to put on a handful of people, no matter how capable.

Without question, some level of control is essential especially since the capacity at the lower level of administration is weak. However, Myanmar’s public agencies need to break with their old habits. To become more agile, the controls need to be rationalised. The simple formula should be “control which adds significant value and let go of the rest”.

Decades of military rule have also left a legacy of risk aversion. As reflected in the saying, “No bad news for the king,” government officials are more worried about being wrong, angering superiors, and alienating other agencies than they are excited to develop better operating models or piloting new initiatives. Without an imperative to act, it is rational to seek ever more information, to await permission or to optimise personal interests rather than work for the organisation as a whole.

The range of stakeholders to satisfy – from citizens to parliament – and increased scrutiny from the media further diminish the willingness of public-sector leaders to take risks. The result is often a lowest-common-denominator recommendation to senior leaders. Changing this mindset will be crucial to achieving and sustaining transformation in Myanmar.

Myanmar’s administrative structure is derived from military rule as much as the colonial period. Public administration is organised along functional lines, with no single unit having end-to-end accountability. This leads to competing priorities and a lack of cross-functional cooperation. Mission responsibility comes together only at the director general level, or higher. What is needed now is a structure of many self-contained units, each with a clear mission, distinct accountability for performance of the mission, and the resources and access to expertise necessary to execute.

Do less, but different, with more impact: a roadmap

The following roadmap can disarm the forces of resistance and increase the agility of the government apparatus in Myanmar.

Why are these steps necessary? Strategy gives employees a clear vision and direction. Organisational structure defines the distribution of people and resources. Processes determine how things get done. And people practices determine who does them and the culture in which they work.

Strategy: The government and each public agency should prioritise a small number of areas (ideally three to six) where they want to achieve breakthrough results and sustained performance improvement, and then define the outcomes they want to achieve. While prioritisation, by definition, involves difficult choices, it ultimately helps leaders to focus their attention and resources on the issues that matter most. The simple formula is, “Don’t do more of the same. Do less, but different, with more impact.”

The government has just released a document with no fewer than 238 measures aimed at boosting the economy, from improving the justice system to reforming state-owned enterprises. But it has set no priorities or laid out how to push all these changes through. The long list of measures makes it difficult for the administration to have a shared vision and purpose to drive the implementation. Clarity about core policies and “how to achieve the mission” are essential and provide the stable backbone for any reform.

Structure: Agile organisations set a stable, simple structure as their backbone. The top team comprises the leaders of departments and core functions, who typically decide how to allocate resources. The dynamic dimension comes from modular teams, which have clear missions and enough autonomy to make decisions. Such teams take end-to-end ownership of processes with clear customers or mission outcomes. All aspects of accomplishing a mission (such as training, acquisition, and execution) are managed by these units. Functional processes (recruiting, finance, IT and so on) provide support to the end-to-end units. In the national-security arena, leaders are well familiar with this system of smaller self-contained teams. Coming in many different sizes, missions, and capabilities, these teams are the organization’s “apps”.

Process: Agile organisations keep their operations stable because standardised, minimally specified core processes underpin their work. These are the essential activities they must excel at to accomplish their mission. Each agency should identify its signature decision-making processes and start from a blank slate. The experience in Myanmar shows that making incremental adjustments to established processes rarely works, as it leads inexorably to a prolonged internal battle. The organization should use as few steps as possible and no more than can fit within the required timeline. Most importantly, the number of reviews must be drastically shrunk to only those that can significantly improve the answer. Doing this will unwind the massive, self-imposed complexity of many of the current processes.

People: But ultimately it is people who accomplish the mission, no matter which structures or processes are in place. Most leaders in the current administrative system rose through the ranks based on mastery of core military and leadership skills critical to warfighting. But achieving and sustaining change often requires not military but management capabilities in fields such as project management, procurement, and public finance. Highly skilled and competent individuals exist in the upper ranks of government but they lack institutional support to implement reforms. Motivating them in the right ways and giving them command to act could make the difference.

Reinvigorating the bureaucracy to meet the demanding tasks of a modern, responsive government will require long-term investment and political commitment. These changes are transformational, not incremental, and require major shifts in mind-sets, behaviours, and capabilities. The government has to adopt an ambitious, structured approach to transform the effectiveness of the state. The organisational-agility model, which blends the stable backbone of core activity with a dynamic capability for rapid insights and change, is a powerful way of taking on these challenges while acknowledging the historical evolution of the public sector in Myanmar. It takes into account the important characteristics of the current system for a successful transition from a military-dominated to a democratically run public sector.