Though soldiers cast ballots outside their bases for the first time in the November election, the military vote enabled the Union Solidarity and Development Party to clinch rare victories in borderland constituencies.

By KAUNG HSET NAING and BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

The military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party has made a flurry of allegations of electoral fraud since its humiliating defeat on November 8. The accusations thrown at the ruling National League for Democracy and the Union Election Commission have been widely dismissed by the public and media – and as reported by Frontier, some of the USDP’s claims appear to have been made in bad faith. However, in a grim irony, the most prominent casualty so far of post-election litigation has not been an electoral or political party official, but a 25-year-old woman who had publicly claimed to be a victim of voter intimidation.

On December 4, a Magway Region court sentenced Ma Thinzar Than Min, the daughter of a medical assistant with Infantry Battalion 235 in Pakokku Township, to nine months’ imprisonment with hard labour. Her alleged crime was posting on Facebook in late September that she and her family had been ordered by her father’s military superiors to vote for the USDP. She was convicted under section 505(a) of the Penal Code, which prohibits “any statement, rumour or report” that would cause any member of the military to mutiny or fail in their duty. She still faces charges of online defamation under the Telecommunications Law, also based on complaints from military officers in the township.

Her conviction generated outrage. Human Rights Watch legal adviser Ms Linda Lakhdhir said, “The Myanmar authorities should be investigating Thinzar Than Min’s allegations of voter intimidation, not prosecuting her for raising them.” But for many in Myanmar, it was easy to see why Thinzar Than Min had been singled out for punishment. Her claims on social media had touched on one of the most sensitive aspects of Myanmar elections – voting by members of the armed forces and their dependents.

While the Tatmadaw refuses to disclose how many people it employs, a rough estimate of up to half a million has prevailed for years, and this number likely swells to more than 1 million with the addition of spouses and children, who often live – and vote – with the troops.

This large voting bloc and the manner in which it casts ballots has been held in deep suspicion since the 2010 general election, which was the first to be held under the military-drafted 2008 Constitution. Although the USDP won easily – in large part due to an NLD boycott – votes from military personnel helped the party win dozens of seats it would otherwise have lost.

Even in the 2015 election, won by the NLD in a landslide, the military vote reliably went to the USDP. While support in the Tatmadaw ranks for a military-aligned party might seem unsurprising, opposition candidates and independent monitors noted a near unanimous preference for the USDP in the ballots cast by soldiers and their family members.

This was widely attributed to the fact that these voters cast their ballots at polling stations located within military cantonments. Contrary to many media reports, these polling stations operated similarly to those elsewhere and were open to observation by party agents and independent monitors bearing UEC accreditation – albeit with some glaring exceptions. However, there was a widespread belief that soldiers felt unable to vote freely while on military premises, regardless of how the polling stations were administered.

Some therefore assumed that, thanks to a recent amendment to electoral by-laws, the election this year would see soldiers and their dependents vote differently. The amendment, passed by parliament in May, required Tatmadaw personnel and their families to vote at polling stations outside their barracks for the first time.

NLD vice chair Dr Zaw Myint Maung told reporters after a meeting of the party’s central executive committee in Nay Pyi Taw on July 2 that the reform “allows military voters to vote freely for the party they support”. However, he added that “we can’t take it for granted” that it will deliver the NLD victories in constituencies with many soldiers.

The amendment, one of several proposed by the NLD-appointed UEC to parliament in late 2019, was opposed by unelected military MPs who raised security and practical concerns about voting outside barracks.

Closer to the election, military-owned newspaper Myawady Daily repeatedly published a passage of voting advice from Tatmadaw commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The advice was initially aired at a meeting with opposition parties on August 14 and urged voters to pick candidates that met six criteria, including an understanding of the “national political leadership role of the military” and a commitment to “protecting race and religion”. Although not explicit, the senior general’s words were widely seen as a tacit instruction to Tatmadaw personnel to stay loyal to the USDP. Myawady Daily was forced to stop publishing the message after the UEC complained to the Press Council on August 31.

Little more than a week after the meeting with political parties, Min Aung Hlaing addressed a ceremony to honour Tatmadaw medics on August 23. In his speech, he warned attendees against choosing the “wrong” candidates on November 8. This only heightened the impression that he was trying to claw back influence over his troops in the election, after the UEC’s decision to relocate military polling stations had loosened a key means of control.

Reform falls flat

Despite the senior general’s voting advice, Tatmadaw representatives insisted ahead of the election that military personnel were free to vote for the candidates of their choice. “We don’t instruct military personnel about which party to vote for,” Tatmadaw spokesperson Brigadier-General Zaw Min Tun told a press conference in Nay Pyi Taw on June 23. “They have the right to vote freely according to their wishes.”

Members of the USDP were also eager to deny that the party benefits from a readymade vote from Tatmadaw families, and tried to play down the significance of the relocation of military polling stations. Incumbent USDP lawmaker for Buthidaung-1 in the Rakhine State Hluttaw, Dr Zaw Zaw Myint, told Frontier that “military voters will vote for the party of their choice regardless of the [polling] location”.

While USDP and Tatmadaw members might be expected to take this line, they were correct to say that little had truly changed. Frontier has dug into results from polling stations reserved for soldiers and their families in a selection of constituencies and found the same overwhelming preference for the USDP seen in previous elections. Frontier has also picked out several constituencies where the military vote delivered USDP victories in closely fought races. These were all in borderland ethnic states, where large military garrisons wield disproportionate influence in lightly populated areas. In this way, it seems, the USDP has been able to sidestep a much-trumpeted UEC reform and retain a rump of seats outside the central Bamar heartland, which went almost entirely to the NLD.

USDP spokesperson Dr Nandar Hla Myint told Frontier the party had “done nothing wrong” in winning these contests, and he had “nothing to say” about military voting.

In some of these USDP victories, the race was not swung by soldiers and their dependents voting on election day, but by votes cast in advance by soldiers serving outside their constituencies. These votes account for a large proportion of overall military votes but the secretive manner in which they are cast was untouched by the UEC’s reform. They remain the most opaque aspect of Myanmar elections, and arguably present the greatest fraud risk. In the 2010 election – and to a lesser extent, 2015 – USDP candidates were suddenly placed ahead in numerous constituencies once advance votes from soldiers were added to the votes cast on election day.

While there are a number of advance voting options, for which different people are eligible, the most important distinction is between in-constituency and out-of-constituency advance voting. The former option is open to people, including government staff, who are unable to vote on election day but remain within their constituencies. Their votes are collected by ward or village tract election sub-commissions shortly before the election, in a way that is easily observable by political party agents and independent monitors. This year, the in-constituency option was extended to all voters aged over 60 to protect this vulnerable segment of the population from potential exposure to COVID-19 at crowded polling stations on election day.

While this greatly expanded process was not without controversy, it represents a model of transparency compared to out-of-constituency advance voting – an option mostly taken up by Tatmadaw personnel. In townships with resident military populations, election sub-commissions posted ballots to soldiers serving temporarily in other parts of the country. The soldiers had between October 8 and 21 to mark these ballots in circumstances arranged by their commanding officers, beyond the view of any election officials, let alone independent monitors or political party observers. The marked ballots then had to be posted back to the relevant township sub-commission for counting on election day.

Some tweaks were made this year to the regulations for advance voting. For instance, advance voters were crossed off voter lists displayed on election day, to guard against double voting. However, this was not a serious transparency upgrade from 2015. In the election that year, copies of Form 1-2 bearing the names of soldiers who had cast out-of-constituency advance votes were publicly displayed at township election sub-commission offices, for anyone to cross-check, and their marked ballots were counted in view of party agents and observers. Moreover, the central flaw in the process – the opaque circumstances in which the ballots are cast in far-off military outposts – had not been addressed.

How advance votes influenced results in the 2010 and 2015 general elections. (Source: UEC; created by Thibi)

A surprise deployment

In the sparsely populated township of Sumprabum in northern Kachin State, Gum Grawng Awng Hkam, vice-chair of the Kachin State People’s Party, watched with dismay on election day as advance votes turned his impending victory into a narrow defeat.

Gum Grawng Awng Hkam was on top in the race for the township’s Pyithu Hluttaw, or Union lower house, seat. Of the 1,625 ballots cast on November 8, the KSPP received 562, the NLD candidate 534 and the USDP contestant 446. But after advance votes were distributed, the USDP took the seat with 856 votes, followed by the KSPP with 787 and the NLD, with 716.

The township election sub-commission refused to tell Frontier the number of soldiers and dependents among the advance voters, citing “security” reasons, and did not disclose how many of the advance ballots were cast inside or outside the constituency. However, in Sumprabum, to focus solely on advance voting would obscure the real electoral kingmakers: a detachment of several hundred soldiers sent to the township in August.

Thanks to a relaxation of the residency rule for transferring your vote to a particular constituency – down from 180 to 90 days’ residency in the area, according to another electoral by-law amendment enacted earlier this year – many of these soldiers were able to vote in the township on election day, rather than having to send advance ballots back to their home constituencies.

Nshang San Awng, who defied the military vote to win one of the two Kachin State Hluttaw constituencies in the township, Sumprabum-2, said about 100 Tatmadaw soldiers were already based in Sumprabum. They were joined in August, he said, by close to 400 soldiers from two battalions, who occupied a local school right up until the election, and who transferred their vote to the township by applying to the election sub-commission.

The township sub-commission put the eventual number of Tatmadaw voters at a more modest 412. Regardless, their presence was enough to swing results in a township of only about 2,000 voters. In the Pyithu Hluttaw race, the USDP’s margin of victory was only 69 votes over the KSPP, and the military-aligned party also took the state hluttaw seat of Sumprabum-1 with a margin of 128 votes over the NLD runner-up.

Kachin has been the site of a renewed civil war between the Tatmadaw and the insurgent Kachin Independence Army since a ceasefire broke down in 2011, but the state has been mostly peaceful since 2018 and both sides have engaged in high-level talks aimed at enabling displaced communities to return home. Residents therefore viewed the deployment of extra troops to Sumprabum with puzzlement and suspicion.

“They told the villagers that they are here for election security,” said Gum Grawng Awng Hkam. “We couldn’t tell whether they had another reason. We could know that only on election day.”

Frontier sought clarification from Tatmadaw spokesperson Zaw Min Tun about the purpose of the deployment, but he could not be reached. He told a September 26 press conference that any troop movements around the election were purely for security purposes.

However, the results from polling stations where the soldiers voted seem to support suspicions of an ulterior motive. The NLD prevailed in five of the Sumprabum’s 12 polling stations, the KSPP in four and the USDP in three. These three stations were reserved for Tatmadaw voters and a smaller number of civilian voters. They were all in the state hluttaw constituency of Sumprabum-1, which the USDP won by a taller margin than the Pyithu Hluttaw seat.

While the mixture of soldiers and civilians at these polling stations muddies the picture, it becomes clearer with the allocation of advance votes, which candidates told Frontier were overwhelmingly cast by soldiers (although the election sub-commission refused to verify this). In one of the locations, the No 2 polling station in Phong In Yang village tract, almost half of the USDP’s 156 votes for the Pyithu Hluttaw seat, at 77, were cast in advance, whereas only 20 of the NLD’s 122 votes were, and only five of the KSPP’s 45 votes.

“I’m very unhappy about being defeated [in this way],” Gum Grawng Awng Hkam told Frontier, adding that the winning candidate from the USDP did not represent the constituency’s residents. “The USDP got all the Tatmadaw votes and I received nearly all the votes of local residents.”

Although this is an exaggeration – the USDP’s 856 votes in the Pyithu Hluttaw race well exceeded the number of military voters – it does appear that these recently arrived voters tipped the balance.

The NLD’s J Htu Raw, the incumbent MP for Sumprabum-1 who lost her seat to the USDP on November 8, told Frontier that these troops started to leave the township after the vote, their work apparently done.

‘I got so depressed’

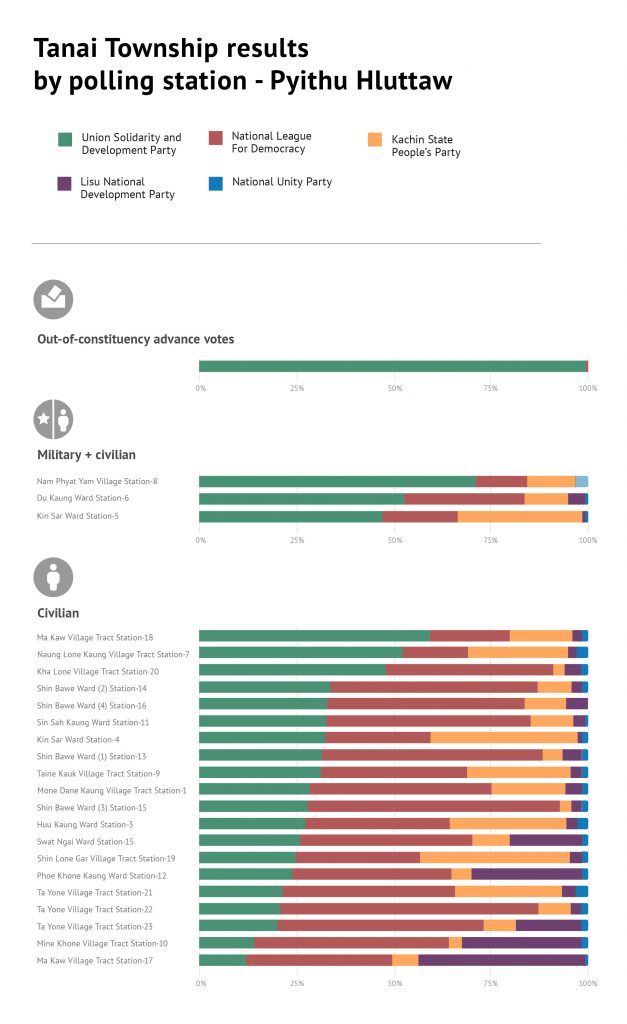

There was a similar story elsewhere in Kachin, in Tanai, which has seen little conflict since 2018, when the Tatmadaw and KIA battled over the township’s lucrative amber mines. The NLD’s candidate for the state hluttaw seat of Tanai-1, Mone Man La, said all the soldiers from the township’s 11 resident Tatmadaw battalions were registered to vote in his constituency, which occupies half the township.

Township election sub-commission data shows that on election day, Mone Man La attracted 3,086 votes and the USDP candidate 2,692 in the race for Tanai-1. However, after the distribution of advance votes, the USDP clinched the seat with 4,540 votes to Mone Man La’s 3,889, with the KSPP candidate trailing with 2,163 votes.

The township’s other state hluttaw seat, Tanai-2, and the Pyithu Hluttaw seat were won by the NLD candidates, with their USDP rivals in second place. However, this was of little consolation to Mone Man La. “I lost the election by only 600 votes,” he said. “I believe that I lost because of the Tatmadaw votes; I won the civilian vote.”

Mone Man La said he won the most votes at five of the constituency’s 10 polling stations. “The KSPP won one station and the USDP won the remaining four, which included the three where Tatmadaw personnel voted,” he said.

The NLD victor in the Pyithu Hluttaw race, U Lin Lin Oo, said there had been more than 1,900 Tatmadaw voters in the township, but this number swelled to nearly 2,100 after incoming military personnel used the 90-day residency rule to transfer their vote from their home constituency to Tanai. This was about 6 percent of a total electorate of 34,349 voters in the township – but in Tanai-1, where all the soldiers were registered, their share grew to 11pc of the constituency’s 18,837 voters.

Lin Lin Oo said that the three polling stations where soldiers voted were in Dukaung ward and the villages of Kinsar and Nanhpyetyan. Because the soldiers shared these stations with civilians, it is impossible to say whether they voted unanimously for the USDP, but the party’s share of the vote was markedly higher than in the civilian-only polling stations. Township sub-commission data for the Pyithu Hluttaw race shows that at the Kinsar station the USDP polled 351 votes to the NLD’s 144, while at the Dukaung ward site it was 958 to 563 votes, respectively, and at Nanhpyetyan village it was 312 to 58.

It was while watching ballot counting at one of these stations on election day that Mone Man La realised he was about to lose the race. “I got so depressed about the result I had to leave the polling station while they were still counting,” he said.

However, the out-of-constituency advance ballots received by the township sub-commission, which overwhelmingly came from soldiers, were even more heavily slanted. These gave 889 extra votes to the USDP in the Pyithu Hluttaw race alone. The NLD received the next highest number, with just nine.

“The gap in the number of advance votes for the USDP and the NLD is too wide to be plausible,” said Lin Lin Oo.

Although he won his Pyithu Hluttaw seat thanks to the support of civilians voting on election day, Lin Lin Oo said the contest for Tanai-1 was a stark example of how Tatmadaw votes can swing elections in areas with small populations. “If the number of voters is low and Tatmadaw personnel vote for one party, it will be a great help to its candidate,” he said.

“In our state where the number of voters is not hundreds of thousands, Tatmadaw votes can change the result.”

Rakhine’s island of green

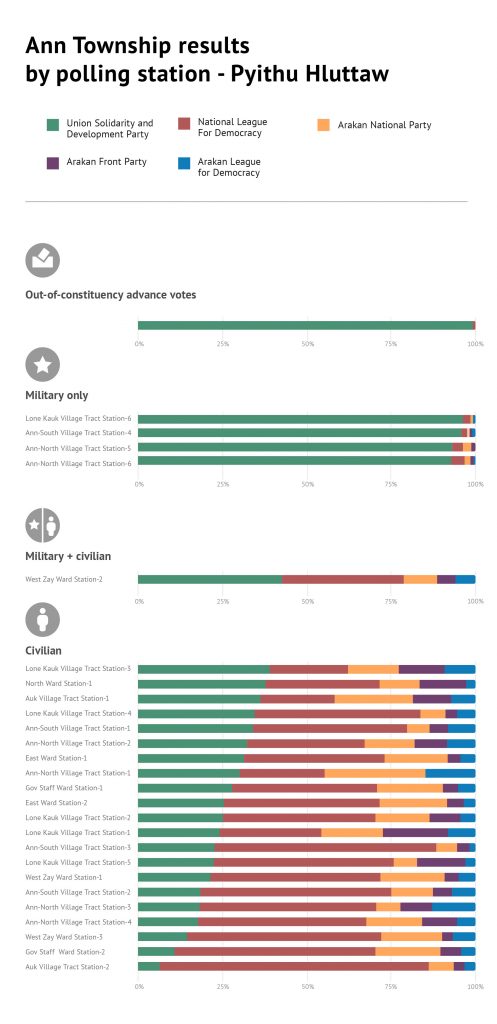

Different circumstances prevailed 1,000 kilometres away in Rakhine State’s Ann Township, headquarters of the Tatmadaw’s Western Command, where the UEC cancelled the vote in most of the township for security reasons. But as in Kachin, USDP candidates gained landslide vote margins both at polling booths reserved for Tatmadaw personnel on election day and in the advance votes cast by soldiers serving outside their constituencies.

Advance votes enabled the USDP to seize Ann’s Pyithu Hluttaw seat, while the party took Ann-1 thanks to Tatmadaw votes cast on November 8.

The USDP has always been competitive in Ann due to the large military presence. It took the same two seats in 2015 with the help of advance votes (though it lost the Pyithu Hluttaw seat to the Arakan National Party in a 2017 by-election). It helped, however, that the cancellations this year magnified the influence of the military vote in the township,

The UEC’s cancellations, which disenfranchised 1.2 million of Rakhine’s 1.65 million voters and denied the vote to smaller numbers of voters in other parts of the country, meant that voting eventually took place in only four wards and four village tracts in Ann. This shrunk an electorate of more than 73,000 voters in 2015 to a little under 23,000 this year.

However, when first announcing cancellations on October 16, the commission said the election in Ann would be confined to the four wards alone, which entailed an electorate of only 9,375 voters, about 300 of which were Tatmadaw personnel. When the vote was later expanded to include the four village tracts on October 27, military voters grew to about 4,000 out of 22,945. This lent these military voters a decisive influence, given that the USDP’s lead over the NLD was 1,478 votes in the Pyithu Hluttaw race and 2,567 in the contest for Ann-1, where most of the soldiers and their dependents voted.

U Tun Tun Naing, the ANP Pyithu Hluttaw candidate for Ann, believes the UEC made this revision “intentionally” to increase the proportion of military voters. He justified his suspicion by saying that, although the UEC was appointed by the NLD, it took recommendations from the Tatmadaw on vote cancellations. “Four village tracts were added to enable more Tatmadaw voters to cast ballots,” he told Frontier.

The Rakhine State election sub-commission said Tatmadaw personnel cast ballots at five of the 26 polling booths in Ann, of which four were used exclusively by the military and one was shared by military and civilian voters. Results from these stations clearly show these soldiers and their families stayed loyal to the USDP.

Election sub-commission data for the Pyithu Hluttaw contest shows that at the No 4 polling station at Ann South village tract, 285 votes were for the USDP and only five for the NLD, three for the Arakan League for Democracy, and two each for the ANP and the Arakan Front Party. At the No 5 polling station in Ann North village tract, the USDP got 936 votes and the NLD 31, with even smaller numbers going to other parties. In the same village tract’s No 6 polling station, 545 votes went to the USDP and 22 to the NLD runner-up. Meanwhile, in Lone Kauk village tract’s No 6 polling station, the USDP got 440 votes and the NLD 11.

“At the 21polling stations where the general population voted, the USDP got fewer than 2,000 votes,” Tun Tun Naing said – less than the party’s tally from the four military-only polling stations.

The USDP also received a large boost from out-of-constituency advance voting, which, as in townships elsewhere, overwhelmingly came from the Tatmadaw. Election sub-commission figures for Ann’s Pyithu Hluttaw contest show that the USDP received 1,179 of these advance votes, while the NLD got just seven, and the ANP and AFP, one each.

“If not for the Tatmadaw votes, the NLD candidate would have won,” Tun Tun Naing said.

Expect more of the same

The USDP owes several other victories in the November election to the military vote. For instance, the party’s winning tally of 1,414 votes for the Kayah State Hluttaw seat of Bawlakhe-1 included 450 out of the 556 votes cast by soldiers and their dependents in the constituency. These votes singlehandedly put the party ahead of the NLD, which received a total of 1,061 votes, of which only 10 came from the military.

Frontier has not catalogued all such USDP wins, but the few that have been highlighted in this article show how ineffectual the current UEC’s most celebrated reform – the relocation of polling stations from Tatmadaw cantonments to civilian areas – was in shifting the voting choices of the USDP’s most dependable voting bloc. We can only speculate whether the voting choices of soldiers and their family members were genuine or coerced, but it remains a particularly serious question in the absence of meaningful reform to out-of-constituency advance voting.

Tun Tun Naing, the defeated ANP candidate in Ann, decried the lack of transparency in advance voting by soldiers but was also eager to point out the largely cosmetic nature of the UEC’s flagship reform. “Although military polling stations were established outside bases, they were positioned right near the entrances,” he said.

In future elections, the USDP will continue to have the edge in sparsely populated constituencies with a heavy Tatmadaw presence. Although unlikely to shift the national balance of power, this phenomenon disproportionately hurts ethnic minority communities and their desire for meaningful political representation. It compounds these communities’ existing grievances over the presence of Tatmadaw units in their towns and villages, which has been a reliable source of human rights abuses for decades, and is likely to foster disillusionment with democratic politics and heighten the appeal of armed struggle.

Moreover, given the current electoral rules, there is little that defeated candidates can do to formally object when Tatmadaw voters determine electoral outcomes.

In Sumprabum, KSPP vice chair Gum Grawng Awng Hkam said he would not be filing a complaint with the UEC because the soldiers who had moved temporarily to the township and voted there had, after all, been acting within the law. “Moreover, we wish for national reconciliation in the long term,” he said.

Nonetheless, he stressed that elections in Sumprabum could not be free and fair so long as Tatmadaw soldiers are able to register as local voters. “Locals could not win an election in this area even if one were held every week,” he said.