The government is planning to abolish a controversial state-owned agency that manages lucrative property assets but much remains unclear about its activities and legal status.

By NYAN HLAING LYNN & THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

AS 14 National League for Democracy lawmakers took turns to lambast the Myanmar International Cooperation Agency during a two-day discussion in the Amyotha Hluttaw last week, one lawmaker was notably absent: U Soe Thane, former Minister for the President’s Office who is now independent representative for Kayah-9.

As the former chairman of MICA, he would be expected to take a keen interest in the debate, and perhaps even shed some light on the allegations of corruption and mismanagement at the secretive government agency, which controls state land assets valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Instead, he was resting up, having recently had surgery on his right eye, he said.

“What they are doing, I have no idea because I’m staying in the clinic and taking a rest at home,” he told Frontier on the morning of February 9, a day after the debate concluded.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Nevertheless, he seemed well aware of the criticisms, which he dismissed as the work of “activists” who didn’t properly understand how MICA was designed to operate.

“Some people are … all negative and all blame, although [what they said] is not true,” he said. “Some people, they think that all these lands are owned by the private people or company or people related to [former Minister for Livestock, Fisheries and Rural Development] U Ohn Myint. It is wrong. It is still in the government ownership.”

MICA had been well intentioned, he said. The aim was to attract private-sector investment into properties owned by the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Rural Development (now part of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation), but ministry staff did not implement it properly, he said.

“I know that some implementations maybe on the thin red line,” he said.

Asked to elaborate, he added: “What I mean is that, for some things the concerned people, their implementation should have been… You had better ask the livestock and fisheries department. I don’t know, I have no idea. We just initiated it.”

Others associated with MICA were less willing to discuss its affairs last week.

When Ohn Myint, the former minister, answered his phone, he initially identified himself. But when Frontier requested an interview, he said that Ohn Myint was travelling and unavailable, and then ended the call. He later answered the phone again and identified himself, but hung up when asked for comment.

Dr Aung Tun Thet, a former economic adviser to U Thein Sein who helped the ministry set up MICA and was one of three non-executive directors, also declined to comment. “It is the decision made by parliament and I am sure they have considered all the issues,” he said.

Unpicking the legacy

On February 8, Deputy Minister for Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation U Hla Kyaw told lawmakers that President U Htin Kyaw had instructed the ministry on December 13, 2016, to dissolve MICA and return its assets to the government.

The ministry was trying to implement the order in consultation with the Attorney General’s Office and other ministries, Hla Kyaw said, but much remained unclear about MICA’s origins and activities. Once its status has been clarified, the ministry will then seek formal Union government approval for MICA to be abolished.

The decision represents a turnaround for the government. In August 2016, the ministry’s deputy permanent secretary, Dr Tun Lwin, told Frontier that it was committed to the MICA project and its board was being re-constituted.

It would continue to seek partners “to increase the government income and promote public and private sector development” in line with the new government’s economic policies, he said.

typeof=

But the government has come under growing pressure from lawmakers and the public to abolish MICA and reveal to the public what it has been doing – particularly the contracts it signed shortly before the handover of power on March 30.

Hla Kyaw was speaking in response to a proposal from Amyotha Hluttaw lawmaker Naw Christ Tun (NLD, Kayin-7) to reveal the “financial and management matters” of MICA to the public. The MP also suggested that the agency was not established in accordance with the law and should be abolished.

“MICA’s activities have changed repeatedly and become complex. Both the ownership and distribution of profit have become more confused,” she said.

Fourteen lawmakers — all from the National League for Democracy — discussed the proposal on February 7 and 8, and all criticised MICA’s lack of transparency. The proposal was approved, with 140 votes for and 50 against.

U Hla San (NLD, Magway-1) said it was still unclear what MICA had done or achieved, while Dr Khun Win Thaung (NLD, Kachin-11) suggested MICA be examined by an investigation team comprising auditors, legal experts, lawmakers and independent experts from the fisheries and animal husbandry sectors.

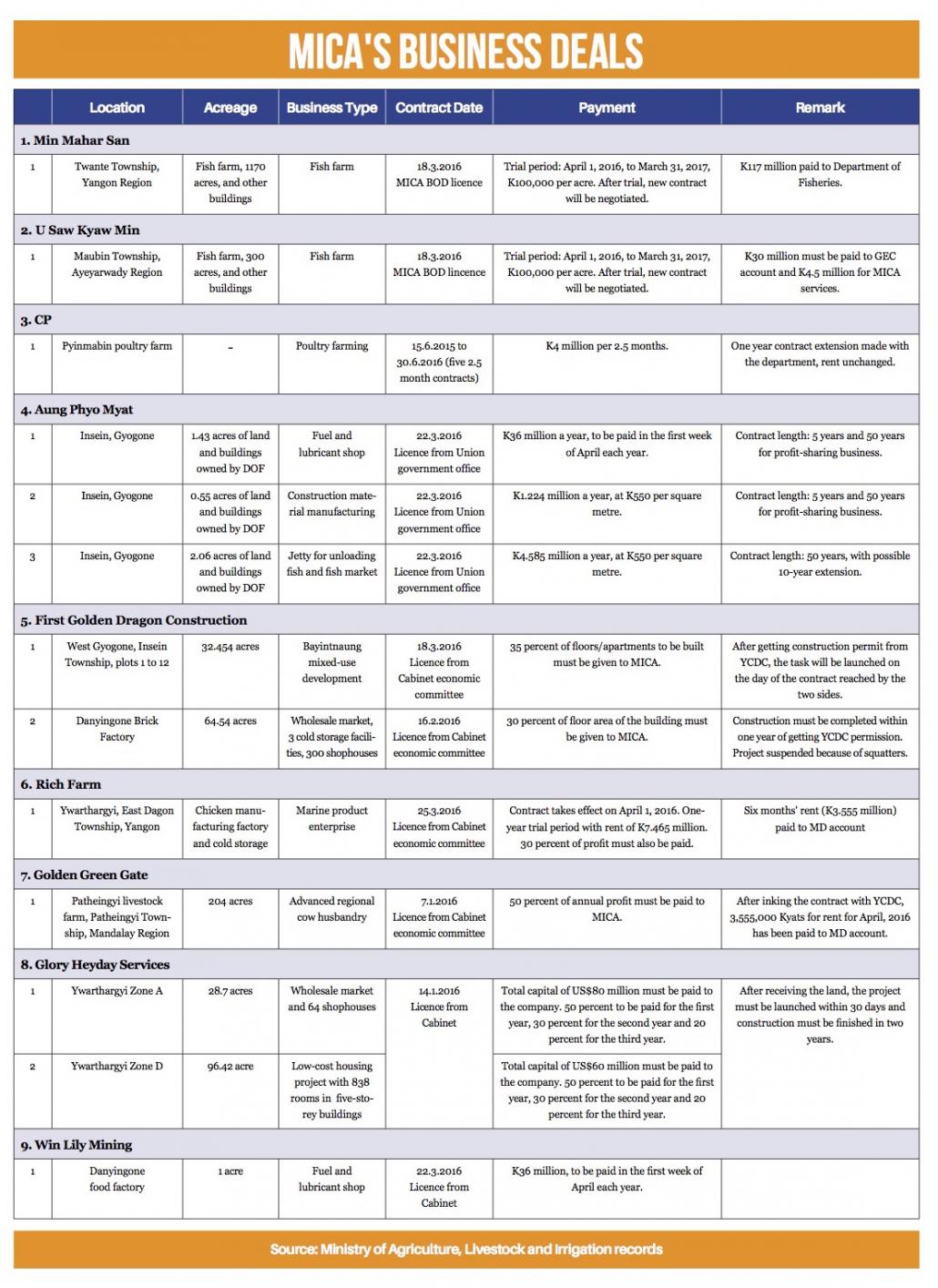

Unpicking MICA’s work will not be easy, however. The agency, which was established by cabinet in August 2014, signed at least 13 contracts with private companies to develop state land formerly used for fisheries and livestock enterprises, according to documents provided to Frontier by a high-level Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation source.

The agreements, which cover 1,900 acres, were nearly all signed from January to March 2016, as the Thein Sein government prepared to leave office.

Hla Kyaw said the ministry was still trying to ascertain the agency’s legal status, as this would dictate how it would be wound up.

The Attorney General’s Office had advised that if it was formed according to the Burma Companies Act of 1914 then it could be abolished through the same law.

It had also told the ministry that if MICA had been given authority to manage government assets then there should be legal instrument to confirm this authority.

The government will have to “clear financial obligations between MICA and other companies according to the agreements made between them and to handover duties and liabilities” to the relevant government departments.

Speaking after Tuesday’s session, Hla Kyaw told Frontier that he was unsure how long it would take to investigate MICA’s activities.

“We have to check its formation and we’ll then look at its financial and contract matters in accordance with the procedures,” he said.

Quiet cooperation

Despite its name, MICA never had a website and rarely released information about its activities. Ministry officials told journalists that it had been formed on the advice of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, but these international agencies denied any involvement.

Frontier drew attention to MICA in September 2016, with the article “Two former ministers, one secretive agency, and some million dollar questions”.

Although chaired by Soe Thane, the impetus for the agency came from the former minister Ohn Myint.

He told Frontier last year it was set up as a “proxy” to work with the private sector to develop ministry-owned assets. It eventually controlled at least 66 properties, including farms, factories and fisheries sites, totalling thousands of acres. Both Ohn Myint and Soe Thane denied any major role in MICA, however, leaving it unclear who was really in charge of its operations.

Former minister U Soe Thane was the chairman of MICA. He did not attend last week’s parliamentary debate during which MPs questioned the agency’s business deals. (AFP)

As the ministry continues its examination of MICA’s books, it is likely to focus its attention on some of the contracts signed in the final months of the former administration, as it was preparing to leave office.

First Golden Dragon Construction signed two contracts with MICA for adjoining plots of land in Insein Township. The first, in February 2016, was for a US$60 million wholesale market, cold store and shophouse project on 64.5 acres. This was widely publicised, with articles in state and private media.

The second, in March 2016, for a “mixed-use project” on an adjoining 32.454 acres, was not disclosed to the public.

The company’s managing director, Sai Myo Win, was travelling overseas last week and unavailable for comment, according to his staff. First Golden Dragon Construction general manager U Tint Swe said he was unable to answer questions about the two projects, including the nature of the contracts with MICA and whether work was proceeding as planned.

“You had better ask the ministry about it,” he said, before dropping the phone.

Another major deal signed by MICA was that with a little-known company called Glory Heyday Services. Under two contracts inked in January 2016, it is slated to develop more than 800 low-cost apartments, 64 shophouses and a wholesale market on 125 acres in Yangon’s East Dagon Township, at Ywarthargyi. These contracts were also not publicised at the time.

Another project is Gyo Gone Jetty. Located near Bayintnaung Market, it was opened by Soe Thane in late January and features a MICA sign on its exterior.

Aung Phyo Myat Company signed three contracts on March 22, 2016, for separate projects at the jetty, and had an investment proposal approved by the Myanmar Investment Commission in July.

But Aung Phyo Myat director U Maung Maung Soe told Frontier that the projects had gone through the Department of Fisheries rather than MICA.

“I applied for the tender at the Fisheries Department. If MICA is abolished, the projects will continue under the relevant ministry,” he said.

The Myanmar Veterinary Association has been one of the most vocal critics of the Insein property deal, which includes land formerly used by the Livestock Breeding and Veterinary Department. Chairman Dr Myint Thein said he was pleased at the announcement that MICA would be abolished.

A former ministry staffer, he was also a MICA non-executive director under the former government. He said that after attending a few initial MICA meetings he was excluded from decision-making, and like the rest of the public he knows little about the contracts that the agency has signed.

“We don’t know deeply what is happening inside [MICA],” he said. “Maybe if some [government] commission investigates the situation, after that it will all be clear. Anyway, we hope for the best,” he said. “Our desire is we would like to maintain and conserve our Insein land. That’s all.”

Kyaw Phone Kyaw also contributed to this report. TOP PHOTO: Gyo Gone Jetty in Insein Township is one of the more high-profile projects undertaken by MICA. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)