The company at the centre of corruption allegations against the Ministry of Electricity and Energy has a controversial past and, potentially, a bright future.

By KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

Electricity meters: it’s a good business – if you can get it.

For decades this market, worth tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars, was closed to competition. Under the military junta, analogue meters were either imported directly from abroad or produced in country under a partnership between the Ministry of Industry’s Heavy Industry Enterprise and Japan’s Mitsubishi.

In the early 2000s, a new player arrived on the scene: Ever Meter. From 2004 to 2016 it enjoyed a monopoly on the provision of analogue and then digital meters to the Electricity Supply Enterprise.

But now it is crying foul.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Ever Meter’s position in the market began to change after the National League for Democracy government took office in 2016 and introduced a tender system to buy digital meters.

Ever Meter won two tenders, in 2016 and 2017, to supply digital meters to ESE but the ministry later cancelled the results. Ever Meter was also one among four bidders that passed the technical test for a third tender in 2017, but the following January the ministry announced it had selected Yangon-based Alpha Power and Junction River Trading Co Ltd, based in Muse, Shan State, to supply ESE with four kinds of digital meters. Junction River signed a contract with ESE worth K14.6 billion, while Alpha Power’s contract was for K1.28 billion.

U Myo Aung, the managing director of Ever Meter Co, Ltd, confirmed to Frontier that he submitted a complaint to the Anti-Corruption Commission after the tender results were announced.

The ACC is investigating senior officials in the ministry, including minister U Win Khaing and his deputy, Dr Tun Naing, but it is unclear whether the probe is related to Ever Meter’s complaint.

ESE managing director U Saw Win Maung said the first tender was cancelled because it was “one-horse race”, and the second because there were attempts to influence the decision.

“Ever Meter passed the technical test in all tender rounds, but it lost the third tender because of its high price,” he said.

On August 21, Tun Naing, the deputy minister, addressed the issue in the national legislature, giving lawmakers a similar version of events as what Saw Win Maung told Frontier. He said that throughout the process Ever Meter had been consistently more expensive than other bidders.

“The decision to purchase meters from [Alpha and Junction River] at lower prices saved K3.0215 billion in total,” Tun Naing said.

“Due to the tender processes since 2016, the ministry was able to purchase meters that are of better quality than those purchased before 2016 and at just half the price.”

A senior ministry official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said Myo Aung had made very serious accusations against the ministry and particularly ESE after Ever Meter lost its monopoly.

“It would be more realistic if he accused us in the past. But now there is a slim chance for corruption,” the official said.

He said many in the ministry were upset at the complaint. “If he [Myo Aung] didn’t have ties to the military, the ministry would probably ban him from tenders in future.”

The rise of Ever

The exact relationship between Ever Meter and the military is disputed, however.

Myo Aung said Ever Meter was established in 2002 after foreign companies withdrew from Myanmar due to economic sanctions. It began supplying analogue meters to the ministry two years later. At first the meters were manufactured in a factory owned by the Heavy Industry Enterprise.

“As the government privatised state-owned factories, I decided to take Mitsubishi’s meter factory that no one was willing to take,” he told Frontier.

“But a meter is not a kind of commodity that can just be sold in market. We had to work closely with government.

“Previous governments encouraged locally manufactured products. That was why my company was able to stand as the only meter manufacturer in the country for several years.”

Since 2008, Ever Meter’s products have been produced with both the Ever logo and that of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd, a military holding company.

All documents related to the meter tenders provided by Myo Aung and the ministry referred to the bidder as MEHL (Ever Meter).

Myo Aung said his relationship with MEHL began in 2008, when he moved production to the MEHL-owned Indagaw Industrial Zone in Bago Region after his original factory in Yangon was destroyed during Cyclone Nargis.

“All products manufactured in the Myanma Economic Holdings Limited Industrial Complex must have its [MEHL] logo. But we are not part of MEHL. That’s very clear,” he said.

Directorate of Investment and Company Administration records show Ever Meter was only registered as a company on June 30, 2016. Myo Aung said he registered the company formally after MEHL transformed into a public company in June 2016.

“MEHL just takes responsibility for marketing,” Myo Aung said. “My factory sold meters directly to the ministry as well as supplied them to MEHL for indirect sales. In return, MEHL made advance payments to my company.”

But officials in the ministry have a different version of events.

“Ever Meter was developed under the guidance of then-leaders in 2000s,” said Saw Win Maung. The company became the sole supplier of meters to the ministry for more than a decade.

“The quality is a bit poor,” Saw Win Maung said. “In our experience the analogue meters broke easily due to weaknesses in their structure and packaging. Some Ever digital meters also had display errors.”

A senior official at the ministry told Frontier that Myo Aung had a close relationship with senior officials in the junta, including U Soe Thane, the former commander-in-chief of the Myanmar Navy who would go on to be industry minister and then President’s Office minister in the government of U Thein Sein.

“Ever is just a brand, but it was manufactured by MEHL. So how can he now say he was never part of MEHL?” said the official. “It monopolised the meter market at high prices.”

Myo Aung denied these allegations, saying Ever’s position as a sole meter supplier was because of government policy. The military regime wanted to encourage domestic production because it lacked the foreign currency reserves to import foreign products, he said.

“U Soe Thane even ordered us to move to new place a week after the factory was destroyed by Nargis. I didn’t have any support from him,” said Myo Aung.

The issue of Myo Aung’s relationship with the military also came up when Tun Naing addressed the legislature. Tun Naing referred to MEHL as the manufacturer of Ever-branded meters, and told lawmakers that during the second tender MEHL had appeared set to lose because the other competitor, Alpha, had bid K5.343 billion less. Myanmar Machinery Manufacturing, a company controlled by Myo Aung, sent a complaint letter to the ministry asking it to review the tender process. Alpha then sent a complaint letter, and MEHL sent a letter directly to the minister asking him to select Ever as the winner. The tender was then cancelled due to interference, the deputy minister said.

Asked for comment, Myo Aung said, “He is a union-level minister and was talking to the union-level parliament so he has to take responsibility for every single word he has spoken.

“He mentioned a letter sent to the union minister by MEHL. I would like to ask if he is able or brave enough to make it [the letter] public,” he said.

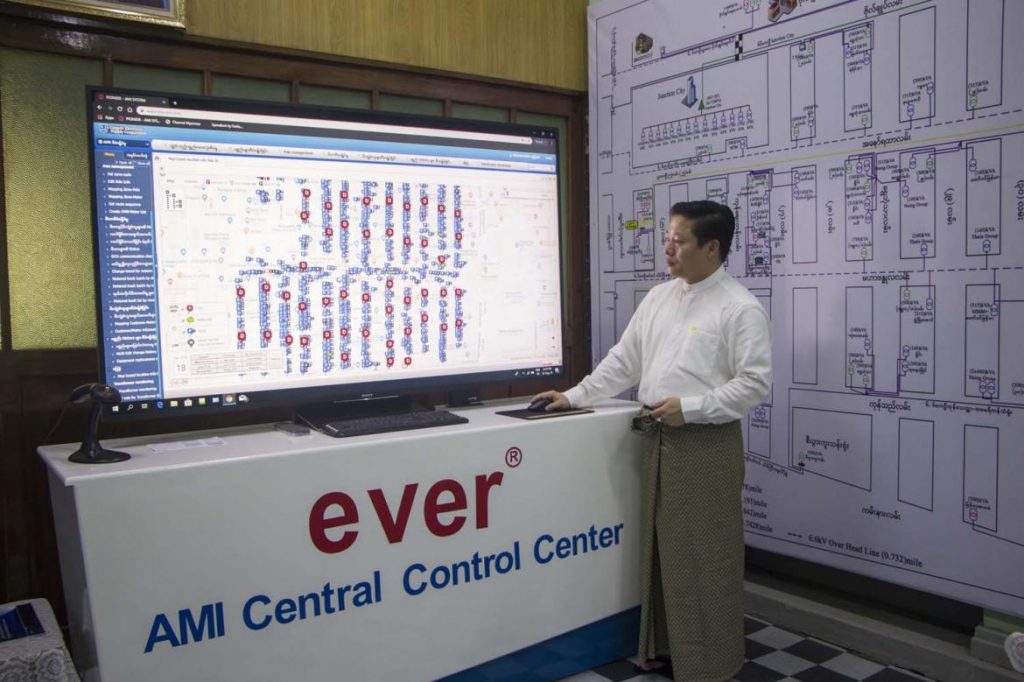

U Myo Aung of Ever Meter Co, Ltd shows an app that his company has developed that would enable users to check their power usage and even turn off their electricity remotely. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Smart meters

The old analogue meters were often subjected to a wide range of tampering methods as users sought to reduce the size of their bills. Officials say it was common for people to use magnets, interfere with the wiring or even use electroshock devices in an effort to trick bill collectors.

“It is impossible to prevent tampering in analogue meters,” said Saw Win Maung. “With analogue meters, the meter reading is also done by humans so non-technical losses were high due to human error.”

In 2012, the ministry began replacing them with upgradeable digital meters to improve metering and bill collection.

Ever installed the first digital meters in Nay Pyi Taw for free, but was soon receiving big orders from the ministry.

Saw Win Maung told Frontier that ESE, the Yangon Electricity Supply Cooperation and the Mandalay Electricity Supply Cooperation have installed more than 4 million digital meters over the past seven years.

Given there are still 1.6 million analogue meters being used, and perhaps another 6 million households are not yet connected to the grid, the potential market remains large.

“Due to budget limitations, we are transforming the system step by step,” Saw Win Maung said. “When we find an analogue or digital meter that is not working properly, we replace it with a digital meter that can be read remotely.”

But Myo Aung, who also runs several other companies, including Same Sky and Myanmar Machinery Manufacturing, said that his factory had not manufactured a single meter since 2016.

Instead, he has focused on installing advanced metering infrastructure, or AMI, across Yangon in cooperation with the Yangon Region government. Based on technology developed in Israel, the AMI system uses data concentration units so that information from digital meters can be transmitted through radio frequency, collected from up to a kilometre away and then stored on a server. It means that meters can be read remotely, without having to go and look at each one, with little possibility for human error.

“It is fully automatic system, and can eliminate the non-technological losses in power distribution,” Myo Aung said, adding that he is promoting the AMI technology Same Sky rather than Ever Meter.

The system was introduced in Dawbon Township in August 2017 and Pabedan Township in December 2018. Myo Aung said financial constraints mean the company has not been able to meet a request from chief minister U Phyo Min Thein to install it in a third township, South Okkalapa.

He said the AMI system had reduced electricity losses by 719,375 units a month in Pabedan and 454,636 units a month in Dawbon, enabling the government to collect tens of thousands of dollars more from customers.

A system for the future

Behind the corruption allegations arising from the meter tender process, Myo Aung and the ministry are engaged in another struggle: which “smart” technology will be used to upgrade Myanmar’s digital meters.

Despite the apparent success of the AMI pilot, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy has not yet approved a request from YESC and the Yangon Region government to expand its use across the city.

Myo Aung said he has “donated” a free licence for the AMI system to YESC for potential use across Yangon. He estimates that the cost of installing it across the city would be recovered in just two or three years.

The technology would work with around two-thirds of the 900,000 existing meters in the city, Myo Aung said. The remaining one-third are mostly analogue and would need to be replaced, but not necessarily with digital meters produced by Ever Meter.

YESC has continued to roll out AMI independently of Ever Meter. The corporation’s temporary chief executive officer, U Aung Kyaw Oo, said that because the pilot project in Pabedan and Dawbon had been successful, YESC had rolled out the technology in South Okkalapa Township and the Shwe Lin Ban Industrial Zone in Hlaing Tharyar Township. The regional government had submitted the results to the ministry, he added.

Asked about the ministry’s refusal to approve the AMI technology, Aung Kyaw Oo said, “Generally speaking, everyone wants to have an automatic metering and billing system.”

Ministry of Electricity and Energy deputy permanent secretary U Soe Myint said ESE, YESC and MESC had been allowed to conduct pilot projects with new technology.

“Based on these pilot projects’ results, the ministry will adopt a standard metering system for the whole country,” he told Frontier last week.

Saw Win Maung, who previously worked at YESC, said he personally favoured the AMI system in high population density areas, such as Yangon.

“But in rural areas with less population density, the system would be costly as it need to use a telecommunication network [rather than radio frequency],” he said.

But Myo Aung said AMI was particularly useful in rural areas because homes are further apart and roads are often poor, which results in ESE staff taking short cuts to avoid having to check every meter.

“We have seen many cases in which staff just guess [the meter reading] instead of actually doing it,” he said.

Myo Aung said he was eager to see the AMI system rolled out across Yangon.

“I can’t earn much money from AMI in Yangon as I’ve already donated the technology to the government. It is for my pride and reputation,” he said. “[But] I will also be able to export the technology to regional countries and expand my business.”