A rift has emerged in the alliance of ethnic groups known as the United Nationalities Federal Council, focused mainly on the so-called Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement.

By THI KHA | FRONTIER

SIX YEARS after it was formed to represent ethnic armed groups in the peace process, divisions have emerged in the United Nationalities Federal Council that threaten its future as a powerful voice for minority interests.

The divisions in the alliance, mainly between its northern and eastern members, have come as the peace process falters and civil conflict continues to ravage parts of Kachin and northern Shan states, where fighting since 2011 has displaced about 100,000 people.

None of the current members of the UNFC, which include the Kachin Independence Organisation, Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North, New Mon State Party, Karenni National Progressive Party and Arakan National Council, are signatories of the so-called Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement signed by eight ethnic armed groups in October 2015. But the NCA is at the heart of the split in the ethnic coalition.

On one side are the KIO and SSPP, together with former UNFC members the Arakan Army (mainly based in Kachin), Ta’ang National Liberation Front and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, which is also known as the Kokang group.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The KIO and these three groups comprise the Northern Alliance, which launched an offensive against Tatmadaw and police posts in Muse Township in November.

These five groups have sided with the United Wa State Army in being prepared to engage in political dialogue with the government but are adamant in refusing to negotiate over the NCA.

On the other side of the divide in the UNFC are the New Mon State Party and the Karenni National Progressive Party, both of which are prepared to continue negotiations on the NCA. Recent media reports suggest they are close to signing.

The government and the Tatmadaw have insisted that signing the NCA is a prerequisite for participation in the political dialogue process, which includes the 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conferences and other gatherings.

Nai Hong Sar, the UNFC vice chairman and a prominent member of the NMSP, acknowledged the differences within the alliance after it held a three-day emergency meeting in Chiang Mai, Thailand, that began on March 12. Without naming any groups, he told journalists on March 14 that some were opposed to negotiations towards signing the NCA, while others wanted to proceed.

The UNFC faces two possible approaches, said Nai Hong Sar. One was the approach outlined by the UWSA at the summit of non-NCA signatories it hosted at Panghsang in late February, at which it rejected signing the ceasefire as a precondition for participation in the peace process. The other approach was for the UNFC to continue negotiations with the government, he said.

Nai Hong Sar said the NMSP favoured the latter option as it had seen some “improvements” in the peace process of late.

In particular, he said that the UNFC negotiating team, the Delegation for Political Negotiation, had been told by members of the National Reconciliation and Peace Centre that the government had “generally agreed” to let all ethnic armed groups join the peace process.

“If we do not know how to handle this problem, our members will become more divided and more fighting will break out in the country,” Nai Hong Sar said.

“We need to find a way to overcome this problem peacefully; but it will take time to resolve the differences,” he said of the rift, which has forced the UNFC to postpone its annual conference that was due to begin in Chiang Mai on March 23.

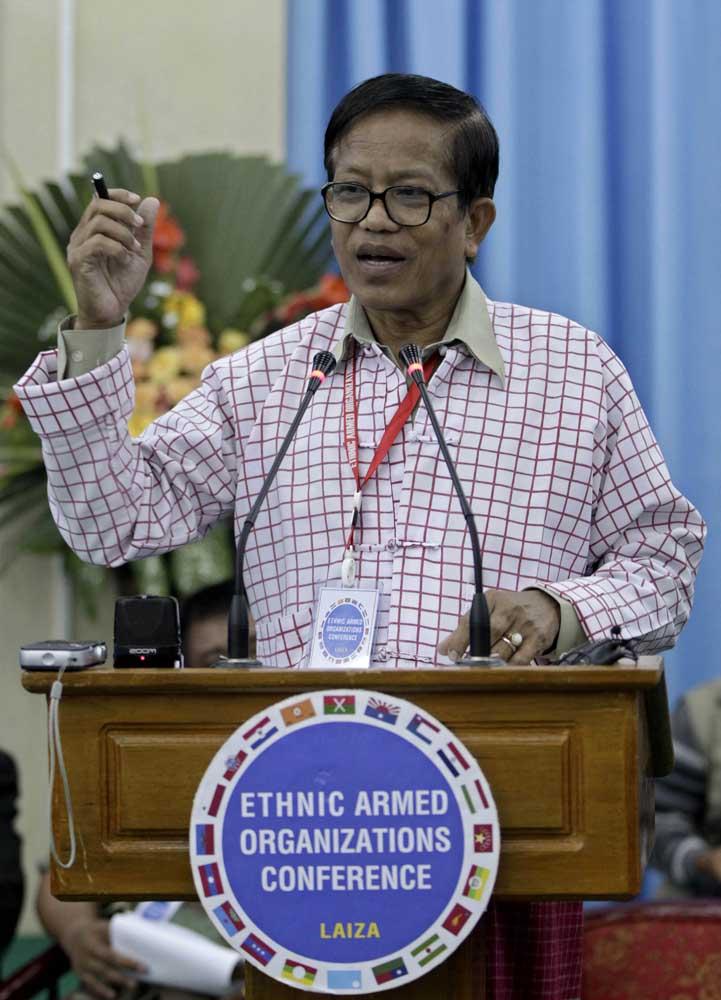

Nai Hong Sar, chairman of the New Mon State Party, talks to members of the media during a November 2013 press conference in Laiza, Kachin State. (EPA)

At the Chiang Mai news conference, Nai Hong Sar called for the Tatmadaw to stop fighting members of the Northern Alliance, warning that there was a risk of the conflict escalating further.

“It is a political conflict,” Nai Hong Sar said. “We need to solve it through political dialogue. Both sides should stop fighting to have benefit for the country.”

Brigadier-General Tar Phone Kyaw from the TNLA said the split was likely only temporary.

“We are all fighting for equal rights for our ethnic people. We all have the same goals and the same destination. We have a different stance today, but our political goals are the same. We will all meet together at the final meeting point,” he said.

When the NCA was signed in October 2015 it was the culmination of more than two years of negotiations between ethnic armed groups and the government, under the peace process launched by President U Thein Sein after his military-backed government came to power in 2011.

However, only eight groups signed the NCA, about half the number involved in the negotiations. The largest of the signatories, the Karen National Union, had been fighting the government for nearly 70 years.

The UWSA and the National Democratic Alliance Army, also known as the Mongla group, were opposed to signing the NCA on the grounds that they had signed bilateral ceasefires with the government. They want to participate in the political dialogue without signing the NCA.

Other groups, including those who make up the UNFC, were prepared to sign the ceasefire provided it was all-inclusive, but the military blocked three groups – the AA, TNLA and MNDAA – from joining the peace process unless they surrendered.

After the National League for Democracy government took office it resumed the process on the foundations laid by the Thein Sein government, but made some changes.

State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said in January 2016 that the peace process would be her government’s first priority. In her first major speech after the transfer of power, on April 18 last year to mark the Myanmar New Year, she said the government would strive to bring non-signatory groups into the NCA. She was also quoted by state-controlled media as saying that “through peace conferences, we’ll continue to be able to build up a genuine, federal democratic union”.

About a week later, Aung San Suu Kyi who had taken a leading role in the process by assuming the chairmanship of the Union Peace Dialogue Joint Committee, announced plans for a series of 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conferences, named after the historic accord negotiated by her father in 1947.

The first Panglong conference began in late August last year and was hailed for the number of groups that participated. However, as the International Crisis Group said in a report last October, the conference “was important for its broad inclusion of armed groups, not for its content”. The Brussels-based think-tank said many groups participated not because they wanted to but because they felt they had no alternative.

Another challenge to the peace process, said the ICG, was weak capacity in the government’s secretariat, the National Reconciliation and Peace Centre, which replaced the Myanmar Peace Center established by the Thein Sein government in October 2012.

The second 21st Century Panglong conference was due to be held at the end of February but has been postponed indefinitely amid continuing efforts to encourage more groups to sign the NCA.

This quest, however, has been complicated by the latest fighting in northern Shan between the Northern Alliance and the Tatmadaw. The four Northern Alliance members, the KIA, AA, TNLA and MNDAA, were joined by the National Democratic Alliance Army at the conference hosted by the UWSA in Panghsang from February 24 to 26.

The groups at the meeting agreed that the UWSA should lead future negotiations with the government. A committee formed for the negotiations is still waiting for an invitation to meet the government.

Among the reasons the UWSA cites for refusing to sign the NCA is the bilateral ceasefires it signed with the junta in 1989 and the previous government in 2011. The UWSA argues that as it has not been involved in fighting, there is no need for it to sign the NCA.

Some media reports about the Panghsang conference accused the UWSA of trying to sabotage the peace process. It responded with a March 4 statement that said the Thein Sein government had tried to implement the NCA to bring peace but the situation had not improved.

The statement said the UWSA did not believe the NCA was fair and this was why fighting had continued, including the recent hostilities in northern Shan on the border with China.

A new approach was needed to overcome the impasse, said the statement, and this was why the UWSA had arranged the meeting in Panghsang.

The meeting was intended to help overcome the difficulties facing the peace process but the government and Tatmadaw misunderstood the UWSA’s intentions, it said.

“At the Panghsang meeting, we did not hold any discussions about holding arms and fighting the central government and Tatmadaw,” it said.

Yangon-based political analyst U Maung Maung Soe said the latest developments in the peace process showed that the Tatmadaw and ethnic armed groups had fundamentally opposing views.

“The priority for the Tatmadaw is to be able to control and disarm the ethnic armed groups. For the ethnic armed groups, the emphasis is more about self-determination – in other words, the right to control their territory,” he said.

“The ethnic armed groups believed that there are not enough ethnic rights in the 2008 Constitution, but the Tatmadaw claims the constitution gives ethnic groups enough rights already.”

TOP PHOTO: Soldiers from the Kachin Independence Army take a rest on the main street of Laiza, Kachin State. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)