The murder of a famous servant of the British Raj in Maymyo nearly 90 years ago was hushed up and there’s speculation that delicate negotiations in London were the reason.

By CHRISTIAN GILBERTI | FRONTIER

EARLY ON the morning of May 17, 1931 in Maymyo, a riderless pony trotted into the compound of Mr Syed Ali – owner of the Maymyo Electric Supply Company – its saddle covered in blood.

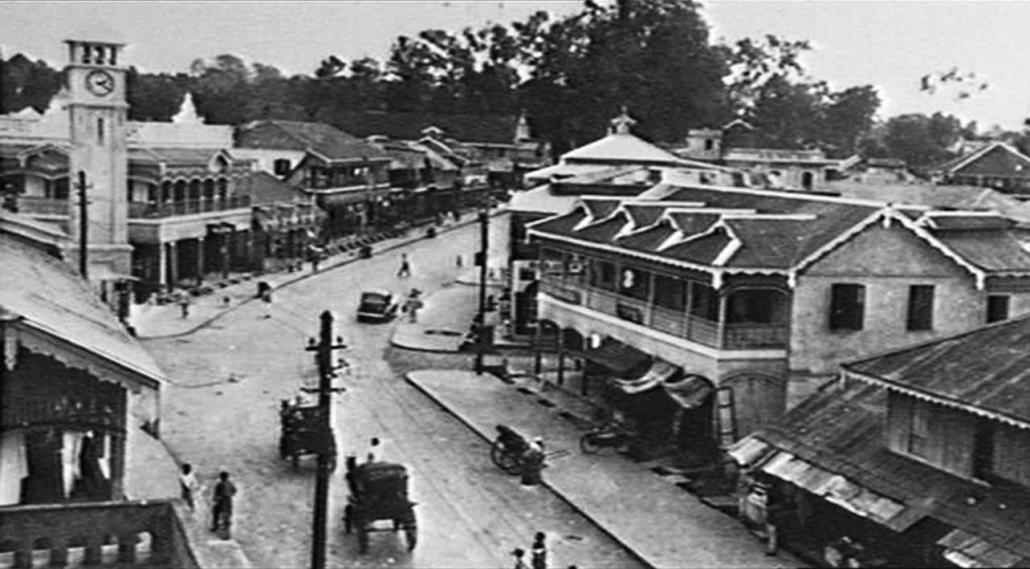

Maymyo, now Pyin Oo Lwin, on the western edge of the Shan plateau, was the main British hill station in colonial Burma, its manicured lawns and prim, hedge-lined paths recalling the idyllic scenery of the English countryside.

It was down one such path that morning that Captain Rawdon Briggs, having received a telephone call from Ali’s house, led a search party of Gurkha soldiers. They retired when night fell and went out early again the next day. At 7.30am Briggs discovered a body in the underbrush, about 200 metres from the path.

The corpse was that of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Morshead, a famous explorer, fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and director of the Survey of India’s activities in Burma. Morshead was perhaps best known for his involvement in George Mallory’s 1921 and 1922 attempts to summit Everest, during which he lost three of his fingers to frostbite, and for discovering the source of the Dihang River in Tibet.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Now he was lying dead on the forest floor in one of the remotest regions of Britain’s colonial empire, a bullet in his chest and one in his back. He had been shot at point-blank range.

The timing of Morshead’s murder could not have been worse for the government in Rangoon. On the night of December 22, 1930, hundreds of miles to the south, a group of armed Burmese peasants, spurred on by the nationalist leader and renowned traditional healer Saya San, had attacked forestry officials near the town of Tharrawaddy, now Thayawady.

Within weeks the unrest spread like wild-fire throughout the rice-growing region of the Irrawaddy Delta and spilled onto the Shan plateau, evolving into a full-blown rebellion against British rule that would take two years, and cost many lives, to put down. The death of a prominent British civil servant would therefore have far-reaching consequences beyond Maymyo.

The Rangoon and London papers quickly learned of Morshead’s death and began to speculate wildly about the identity of the killer. The rebellion was still under way and dacoits – gangs of armed rebels – had been seen near Maymyo the night before the murder. There had been other attacks. Perhaps the murder was part of a larger plot against the British administration at Maymyo? The government began to conduct inquiries and quickly arrested two local residents – a Gurkha and a Burman.

The Gurkha admitted to having gone hunting near where the murder occurred with a gun borrowed from the Burmese man. He said that he mistook Morshead for a stag and fired at him, hitting him in the back. But when he realised his mistake, and Morshead advanced on him to take the gun, it went off in his hand, hitting the Englishman in the chest and killing him. The Gurkha even had a bruise on his head to suggest a struggle.

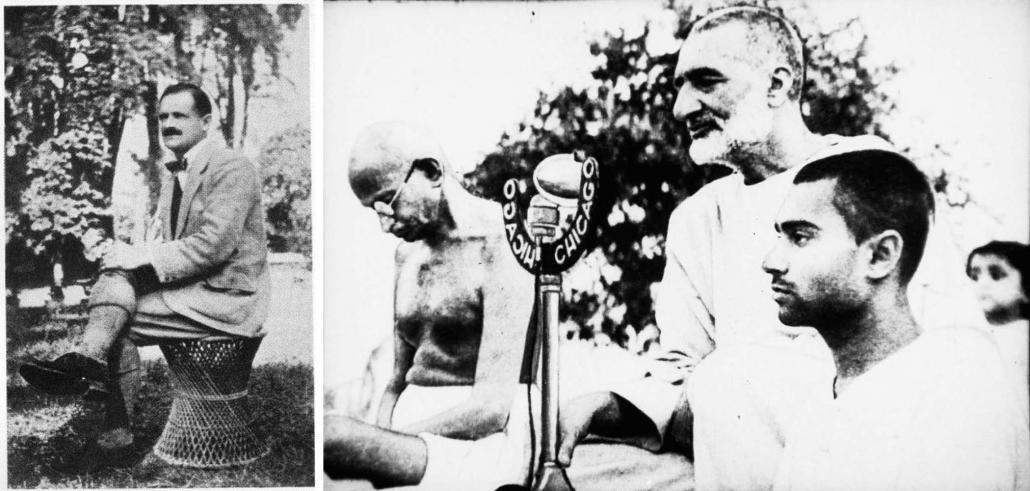

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Morshead (left) and Mahatma Gandhi with close associate Bacha Khan (centre), who was often referred to as the “Frontier Gandhi” and the “Pride of the Pashtuns”. (Supplied)

But the final police report was ambiguous. The Gurkha’s story could not be true, it said, because it was impossible to cover the distance between his house and the scene of the crime on foot in the time required by the sequence of events. Both men were released, and it was determined that there was “no evidence to connect the attack with rebel activity” – even though dacoits had been seen in the area the night before.

Ultimately, the imperial government in Whitehall, London, declared that “the case must remain a mystery”.

But Morshead’s family wasn’t satisfied, and in the early 1980s his son, Ian, returned to Burma to try to uncover the truth about his father’s untimely demise.

Arriving in Maymyo, a town he remembered well from his childhood, Mr Ian Morshead began seeking clues to his father’s death.

One thing stood out in the reporting: the riderless horse had returned to Syed Ali’s compound and not to Morshead’s house. Ian realised from looking through his father’s diaries that he often looked after the horses of neighbours. From this he surmised that it must have been Ali’s horse. And if the horse belonged to Ali, was it possible that he had arranged the killing?

Ian asked his aunt Ruth – who had been living with her brother at the time – about Ali and she said that Morshead hated him. Morshead reportedly had a nasty temper and, as a regular old sahib, was quick to throw a book at his Burmese teacher or to discipline his servants. Was it possible that one or the other of the men had held some sort of a grudge against Morshead?

As Ian walked the tulip-lined lanes of Maymyo, a tip led him to the house of Mr John Fenton, an elderly Anglo-Burmese man. Fenton claimed that he had seen Ali out riding one day with “a lady” related to Morshead, by whom he meant his sister, Ruth. He also told of a rumour heard at the time that Morshead had objected to Ali riding with the woman and wanted to confront him. Soon after the murder, Fenton said, Ali left Maymyo.

This added a new dimension to Ian’s search and provided him with the twist to his book on the subject of his father’s death, The Life and Murder of Henry Morshead: A True Story of the Raj, published by Oleander Press in 1982. Returning to England, he sought out his aunt Ruth who denied ever having spoken to Ali. But she was also evasive, saying that “no one ever consulted me, or asked my opinion”. She once even lamented, “Will this thing ever go away?”

Upperfold, the Morshead family home, still stands in Pyin Oo Lwin. (Christian Gilberti | Frontier)

In his book, Ian suggested that the police had covered up the investigation for fear of besmirching Ruth’s honour. The implications at the time of an English woman having a relationship with an Indian man, even one so innocuous as a ride in the forest together, were grave. Ian, who died in 2013, concluded that the police had deliberately suppressed the murder investigation to save Ruth the embarassment of a trial.

But the strangest episode of the story was yet to come. In a post-script written after the publication of his book, Morshead visited Lahore in Pakistan to deliver a copy to his cousin, BBC correspondent Mr Mark Tully.

While there, he dined at the home of two Pashtun brothers he had met in London and it quickly became apparent that they were none other than the grandsons of Syed Ali. Morshead even met Ali’s son, Rahmat, but did not reveal who he was.

When I found Morshead’s book in the British Library in London, long forgotten and long out of print, it all seemed too fantastic to be true. I wanted to know more, so I began to dig.

The first thing I discovered was that Syed Ali’s real name was Abdul Ali Hamid, and he was a wealthy and important man.

Hamid was a Pashtun from Peshawar, in what is now Pakistan. He emigrated to Burma in 1909 and started a number of successful businesses. He was a bit of a play-boy who liked riding and shooting, and he lived in one of the largest houses in Maymyo – Manor House – which still stands. Just across the road was the Morshead family home, Upperfold, which also still stands.

Suspected murderer Ali Hamid, wealthy businessman of Maymyo (Who’s Who in Burma, 1927, supplied)

Later, I decided to write a blog post about the murder and how it related to the politics of Burmese nationalism at the time. A writer commented on the post saying that he knew members of the Morshead family and asked whether I would like to speak to them. I said I did, of course. All of a sudden history was coming alive.

Eventually, I would hear from many members of the Morshead family, but they all directed me to Henry’s grandson, Tracy. He maintained the family archive and had his father’s notes for the book.

I telephoned him late one afternoon this August to ask a few questions, but at first he was evasive.

“There are some things I don’t know,” Mr Tracy Morshead said. “And then there are some things I know and won’t tell you.”

He was wary of me for a reason. The publication of Ian’s book had caused a rift in the family, with some members arguing that he should have waited until Ruth died before it was published. Henry’s brother was Sir Owen Morshead, the royal librarian at Windsor Castle from 1926 to 1958, and the attention that the book brought was not entirely welcome.

“I have no intention of moving history backwards again and opening any kinds of wounds,” Tracy said. “The current generations are happy with each other.”

But as we got to talking, he began to fill in some of the gaps that his father had left open. The first thing he said was that the post-script was entirely true. “It all happened,” he said. “I can vouch for it.”

But some things about the murder, he agreed, did not add up.

“Henry’s death was announced in parliament,” Tracy said, “and then absolutely nothing from any newspaper as a follow-up.” He said the stifling of the story sounded “like a D-notice to me”, referring to a British government instruction to prevent information from being published on the grounds of national security.

It was true. The newspapers had only followed the story for about two months, until August 1931.

Then Tracy proposed a theory that I had not heard previously. In 1930, Gandhi led the Salt March in resistance to British rule in India just as Indian nationalists began meeting British politicians for a series of Round Table Conferences in London to agree to a framework for dominion status and a degree of self-rule in India.

The main street of Maymyo, now Pyin Oo Lwin, in 1941. (Supplied)

What Tracy said suggested a much larger conspiracy to cover up the crime. The Viceroy of India, Lord Irwin, and the Secretary of State for India, Mr William Benn, were anxious for peace in India, and at the time of Morshead’s murder the British government was trying to get Ghandi to come to London for the conferences, which would continue through to 1932. Tracy claimed that Hamid had family connections to Gandhi’s right-hand man, the Pashtun leader Bacha Khan, who was known as “the Frontier Gandhi”. “The last thing they [the British government] would want is a senior officer being taken out by someone who was on the negotiating side,” said Tracy.

Although Tracy did not respond to requests to corroborate his argument, it was a convincing one. It also made a lot of sense when the Burmese context was considered. Burma was a province of British India at the time, and its fate was to be decided at the Round Table Conferences. Among the Burmese delegation was U Chit Hlaing, the nationalist and future member of Burmese parliament.

Under the 1929 Simon Commission, the British were busy readying Burma for political separation from India. A high-profile murder of a British civil servant in such a political climate might have bolstered the argument that Burma was not politically ready for separation, or that the safety of British officers in the country could not be ensured without the help of the Indian Army. Fear that Indian nationalist agitators were fuelling disturbances in Burma might also have stoked the flames of suspicion against Hamid and necessitated a cover-up.

“Why did a local police officer sign the final report and no British officer?” Tracy asked me. “It was a shut-down,” he concluded.

We may never know the truth about what happened that day in Maymyo as all the interested parties are dead. But the murder of Henry Morshead remains interesting to this day for the light it sheds on British colonial policy in India, the long-standing relationship between India and Burma, and the dynamics of ethnic conflict in modern Myanmar.

Fighting continues near Pyin Oo Lwin not far from where the Saya San rebels were seizing police posts and shooting colonial officials in 1931. Pyin Oo Lwin itself was attacked on August 15 in a series of coordinated operations by three armed group members of the Northern Alliance.

Now, as then, relationships between Buddhist women and Indian Muslim men are highly censured in Myanmar and now, as then, fear of foreign influence (real or imagined) is fuelling repressive measures against largely defenseless populations.

We can learn a great deal about our world – our preconceptions about race, immigration, nationhood, and government control – from stopping to take a momentary glimpse into the often mysterious past.