Friends of the Union Election Commission chair describe a passionate democrat, but opposition parties accuse him of bias and observers say a failure to communicate has undermined trust in the commission.

By EI EI TOE LWIN | FRONTIER

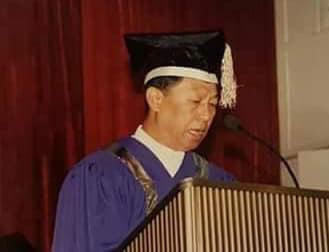

When U Hla Thein was picked to be the next head of the Union Election Commission in March 2016, his appointment took many by surprise.

The former university lecturer had led the district election sub-commission in Meiktila in Mandalay Region since 2010 but was little known in political circles. Without a military background, he also marked a significant departure from outgoing UEC boss U Tin Aye, a former Tatmadaw lieutenant-general, and his predecessor, former major-general Soe Thein.

For much of his term, and even into the campaign period, Hla Thein has maintained his low profile, rarely meeting with election stakeholders, much less the media.

But as the election draws closer and complaints rise over the UEC’s handling of the vote, Hla Thein’s leadership has increasingly come into question.

The many issues raised include the disenfranchisement of ethnic and religious minorities, notably the Rohingya, the seemingly uneven cancellation of voting in conflict areas, and the commission’s perceived bias in favour of the ruling National League for Democracy.

The UEC has also been forced into a number of embarrassing backflips, most notably on allowing Myanmar’s largest observer group the People’s Alliance for Credible Elections to monitor the vote. On October 27, it announced revisions to where voting would be cancelled for security reasons, following criticism from ethnic-based parties and observers of its earlier announcement.

So, who is the man leading Myanmar’s controversial electoral management body? The publicity-shy Hla Thein declined a request for an interview Frontier submitted back in August, and there is little publicly available information about him. But interviews with political insiders as well as friends and former colleagues reveal a person who believes strongly in democracy, but is also uncompromising and intolerant of criticism.

‘He deserves the position’

Hla Thein, 72, was born in the small village of Thapyay Taung, in Myittha Township just south of Mandalay. He left the rural dry zone to attend university in Mandalay, and attained a masters in geology before joining Mandalay University as a lecturer in 1980. During a 28-year academic career, he served at universities in Magway and Kengtung and gained a Diploma in Geological Survey from the International Training Centre (now part of the University of Twente) in the Netherlands, before retiring as rector of Meiktila University in 2008.

U Soe Myint, who met Hla Thein in 1998 when they were both lecturers at Mandalay University, described him as someone who has the “nature of a teacher” and “lives peacefully”.

“He deserves to take the position,” Soe Myint said, referring to Hla Thein’s role as UEC chief. He said he gets upset when he sees his friend – who he refers to as “sayargyi”, or revered teacher – being criticised by the public or in the media.

As an example, Soe Myint cited media accusing Hla Thein of undermining the independence of the UEC after a photo emerged of him paying respect to State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in 2017.

The photo, which circulated widely on social media, also featured some Union ministers and heads of other Union-level organisations paying home to the National League for Democracy chair, but Soe Myint said Hla Thein had been singled out unfairly.

“Among all the government officials, only Hla Thein was criticised,” Soe Myint said. “He respects Aung San Suu Kyi and he is a religious person – he did it unintentionally.”

U Thein Paing, who worked under Hla Thein at Meiktila University, described his old boss as someone who is strict about enforcing rules, and makes sure to adhere to them himself. He referenced an incident at the university, when Hla Thein banned the use of motorcycles on campus because he viewed them as a disruption.

“One day, he saw a woman tutor with a motorbike inside the compound and told her to pay a fine. The woman tutor was angry, and complained that, as a teacher, she should be exempt from this rule. Sayargyi [Hla Thein] didn’t accept this, and gave her a warning and told her to pay the fine,” Thein Paing said.

Thein Paing also described Hla Thein as someone who is respectful to his superiors and “very good to his staff”.

“But he is quiet and unsociable. That’s why people who don’t know him have a different view,” Thein Paing said.

Although well-regarded by colleagues – or at least some of them – Hla Thein was basically an unknown when he was elevated to lead the UEC.

Many saw the hand of U Win Htein, an NLD powerbroker and Meiktila native who hand-picked many important appointments after the party’s election win in 2015.

The pair met when Win Htein successfully ran as the NLD candidate for the Pyithu Hluttaw in Meiktila in the 2012 by-elections.

Win Htein told Frontier he had a close relationship with Hla Thein and had “recommended” him for the position because of his “good reputation”. However, he said the party’s Central Executive Committee made the final decision.

“He has a good record of service in the education field, and as a teacher he is patient, honest and calm. As someone who headed of a district election body, he knows about the electoral process. Most importantly, I trust he believes in the democratic process,” Win Htein said. “But I couldn’t decide alone.”

Hope for change

Having succeeded two former generals, many in Myanmar’s political community hoped Hla Thein would build the independence and capacity of the commission, and oversee the smooth management of the 2020 general election.

The commission has taken some important steps to improve the legal framework. The most widely reported of these was a change requiring military personnel and their families to vote outside cantonments, but the international monitoring group The Carter Center noted in a pre-election statement several other reforms passed in June this year. These changes formalise the role of election mediation committees, require election sub-commissions to help people with disabilities to ensure they are able to vote, acknowledge the right of observers to be in polling stations and provide for the replacement of a ballot a voter accidently spoils during polling, the group said.

Hla Thein has promised that the November 8 general election will be a “model” election held according to five criteria: freedom, justice, transparency, credibility and consistency with the will of the people.

The coronavirus outbreak has undoubtedly made the task of holding the election far more difficult, but some observers say there were already signs that the UEC was likely to encounter problems.

The Carter Center, for example, noted that elements of the electoral process that it had singled out for reform after observing the 2015 election – including the dearth of transparency in out-of-constituency advance voting by military personnel, and the lack of gender balance on the UEC – have not been addressed. Advance voting by Tatmadaw soldiers and their families remains a black box, and there are no women on Hla Thein’s commission.

Insiders also say that over the past four-and-a-half years, the commission has also made little progress on building its institutional capacity and failed to engage adequately with political parties, civil society groups and the media.

During the 2018 by-elections, the UEC was criticised for major errors in the voter lists. Flaws in the electoral roll reappeared this year, when lists went on display for three weeks back in July and August, prompting Aung San Suu Kyi to raise the issue in a public teleconference with both UEC member U Myint Naing and Minister for Labour, Immigration and Population U Thein Swe.

As the election has neared, the complaints have grown to include the censoring of political parties’ speeches on state media, the way voting has been cancelled in some ethnic minority areas for inadequately explained security reasons, and the commission’s unwillingness to push back the election despite high numbers of COVID-19 infections. In each case, the commission has been accused of bias in favour of the NLD.

‘An insult to political parties’

The lack of trust in the UEC stems in part from the constitution, under which the incoming president picks commissionmembers whose terms are tied to those of the government.

In a country that lacks a culture of strong, independent political institutions, many see this as highly problematic.

“Unless the 2008 constitution is amended, criticisms that the commission is biased and unfair will reappear every five years,” said U Han Shwe, vice chair of the National Unity Party, which has competed in all elections since 1990.

Hla Thein has urged political parties and other stakeholders to trust him, but they insist that he must prove he is unbiased by creating an electoral landscape that guarantees fairness for all of those competing.

The lack of dialogue between the current commission and key stakeholders – including parties, observer groups, civil society and the media – has undermined that trust.

Inevitably, some are drawing unfavourable comparisons between Hla Thein’s commission and that of his predecessor, Tin Aye.

Prior to the 2015 vote, there were questions raised about the impartiality of a UEC run a former military man who won a seat for the Union Solidarity and Development Party in the 2010 election. Although there were problems, including the disenfranchisement of the Rohingya and a comprehensive lack of transparency in out-of-constituency advance voting, Tin Aye was credited with overseeing a mostly free and fair vote.

“The [current] commission cooperates very little with political parties compared to U Tin Aye’s time,” said U Thu Wai, chairman of the Democratic Party (Myanmar), which formed in 2010. “As other parties have said, by looking at its management of the election it is very clear that the UEC is biased.”

Sai Ye Kyaw Swar Myint, executive director of the People’s Alliance for Credible Elections, said that the current UEC is a “step backwards” from the past. Regarding election observation, he said the commission members seem to dislike the idea of their performance being scrutinised.

“I think they are very nervous about discussing issues openly,” he said, adding that this had damaged trust between the UEC and other stakeholders. “With the previous commission, there were serious debates with CSOs. Some problems couldn’t be solved, but at least we could talk.”

However, National Unity Party vice chair Han Shwe said Soe Thein, who oversaw the 2010 vote, was the worst commission chairman he had encountered, and was a man who “did what he wanted”.

“U Tin Aye was biased as well,” Han Shwe said. “However, there were negotiations, not only with the parties, but also with civil society and the media. Under U Hla Thein, this rarely ever happens. He only meets with the parties once a year.”

Another difference with Tin Aye’s commission is in how Hla Thein and his colleagues engage with the media – or, rather, how they don’t.

UEC press conferences are usually led by commission member U Myint Naing, with Hla Thein rarely present. It is very difficult for journalists to get comments from commission members, and Hla Thein has rarely given interviews. He seems “afraid of talking to the media”, Han Shwe observed.

Tin Aye also had a complicated relationship with the media, but he was anything but afraid. Journalists recall how at onepress conference in November 2015 that Tin Aye had delegated to another commission member, he emerged mid-way through the event to take over – apparently unhappy at his colleague’s inability to answer questions.

Although Win Htein cited Hla Thein’s patience when discussing the former rector’s suitability for the UEC chief role, in his rare encounters with reporters the commission chair has appeared sensitive to criticism. In an interview (published in two parts) with Radio Free Asia on August 14, Hla Thein, when asked about errors on the voter list, interrupted the reporter and responded, “Is there a voter list anywhere that doesn’t have errors?”. In response to one tough question, he replied, “Why did you ask me that question? Why not before [to the previous commission]?”

He has also upset political parties with his comments. In June, during a two-day meeting to discuss a code of conduct for parties and candidates to abide by in the run-up to the vote, a heated argument broke out between commission representatives and opposition parties, including the USDP, over the use of images of Bogyoke Aung San. Some political parties asked the commission to change the code to ban the use of the independence hero’s image in campaigns. When Hla Thein refused, dozens of parties refused to sign, including the USDP.

During the negotiations, Hla Thein provocatively told parties to focus on encouraging people to believe in them rather than expressing doubts about the fairness of the commission. “We were amazed at what he said. He is very rude,” U Nandar Hla Myint, a spokesperson of the USDP, said at a press conference after the meeting.

At a meeting with civil society organisations in Nay Pyi Taw on July 17, rather than trying to make amends he stuck the boot in further by repeating his claim that political parties should focus on gaining public trust rather than criticising the commission, saying that most parties failed to win seats in 2015 because the public didn’t trust them.

“It is an insult to political parties,” Nandar Hla Myint said of Hla Thein’s comments.

Many politicians hold Hla Thein personally responsible for the commission’s shortcomings. When 34 opposition political parties, led by the USDP, held a meeting with Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing on August 14 to raise concerns about the election, some participants in the meeting called for Hla Thein to resign.

A complex organisation

Thein Paing insists the criticism of his former university colleague is unfair. Hla Thein, he says, is impartial and neutral, but he is also working under significant pressure in a complex organisation.

Thein Paing said the former rector must coordinate with several different government departments to administer the election at the local level, and these departments are not always cooperative.

For the 2018 by-elections, Thein Paing was made chair of the Tarmwe Township election sub-commission in Yangon at the recommendation of Hla Thein, and he said the process of successfully holding an election is not as straightforward as many people think.

“Even if you want to do it right, there are things that can cause you trouble,” he said. “In my experience, there were some very difficult situations to deal with. It’s impossible to expect other staff to listen and follow what you said.”

Thein Paing, who has since resigned from the UEC, said dealing with political parties was also challenging. He pointed to the time he issued a warning letter to the NLD campaign team in Tarmwe to follow campaign rules.

“I was told [by NLD members], ‘Why did you issue a warning to the party?’. They assumed I shouldn’t do it because the commission was appointed by the NLD,” he said.

Thein Paing argued that Tin Aye’s job of overseeing the UEC was easier than Hla Thein’s because, as a former general, he was better protected from external criticism and faced fewer internal obstacles.

“Sayargyi [Hla Thein] is not like that. He is only one [person] and no one backs him. Because of that I say Sayargyi is doing his best in a complex situation,” Thein Paing said.

Despite the widespread criticism, Hla Thein is determined to fulfil his responsibilities, said his former colleague Soe Myint.

“He phones me every day to talk about personal matters. He doesn’t complain about his work – he’s still enthusiastic about the job,” Soe Myint said, adding that Hla Thein told him to “go ahead” when he said he was being interviewed by Frontier for this article.

Soe Myint said Hla Thein rarely discusses work outside of the office, except to share information about voter lists and the rules for advance voting.

With just days to go until election day, the UEC is under greater scrutiny than ever. The commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing has even weighed in, describing “weakness and deficiencies which were never seen in previous elections” in a statement put out by his office on November 2 in which he cast doubt on the fairness of the election.

With more parties than ever competing, outbreaks of violence on the campaign trail and recurrent complaints of bias against the UEC, the post-election period could be a turbulent one for Hla Thein and his fellow commissioners.

The UEC chair has insisted that he is treating all parties fairly, and will continue to do so until his term ends in March 2021.

“We are not biased against any party,” he said in the RFA interview in August, and warned everybody to follow the electoral rules. “No one is above the law.”