U Sonny Aung Khin, owner of traditional Myanmar restaurant Padonmar in Dagon Township, discusses his five decades in the tourism industry, including 16 years in Bangkok sending curious foreign visitors to socialist-era Burma.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

You’ve been in the tourism industry for 50 years, starting out in the early 1960s. How did you get your start and what were the challenges working in Yangon then?

I started my life in the travel industry by joining BOAC – later known as British Airways – in 1960 and then worked at Air France from 1971 to 77 as a sales representative. In those days the airline sales staff had to go around to the government departments, embassies and so on to look for the passengers to fly on our airline – there were no cheap flights in those days.

My duty was to send off all VIP customers at Mingaladon Airport each morning. There were no taxis or buses in those days so I relied on my Volkswagen Beetle. If there was a problem with my car, my faithful mechanic Mr Rajan would sometimes have to spend the whole night repairing it to make sure it was running the next morning.

Often he’d work by candlelight and then pick me up from my home and drive me to the airport in the morning, still wearing his dirty, oily mechanic’s outfit. The first Mazda B600 taxis (known in Myanmar as ley bein, or four wheels) didn’t come into service until years later.

You left Yangon for Bangkok in 1978 but remained involved with Myanmar’s tourism industry. How did that come about?

I moved to Bangkok to work for a tour agency. We were looking to introduce a new product and found that tour promotion to Burma was monopolised by only one tour operator: Diethelm Travel. The reason was that top Thai tour operators who previously promoted tours to Burma stopped because of bad communications and poor service of Tourist Burma (TB), which was then under the Ministry of Trade.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

When the Thai operators wrote to TB for information, programs, quotations and so on, they didn’t get any response for many months and therefore got fed up and stopped promoting Burma altogether.

U Sonny Aung Khin in his office, surrounded by photos and other mementoes collected during more than 50 years in the tourism industry. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier(

They could have got quick results if they worked through Diethelm Travel but since they were great competitors for Thai inbound business, they didn’t want to. After 16 years with airlines in Yangon I had many close contacts in the travel industry.

I proposed to the Thai operators that I could get quick results and service for tours to Burma, and they all agreed to try again to promote as there were many inquires for Burma and they had lost out on this business. The name of the agency was Burma Cultural Tours (BCT).

So how did you solve the communication problems with Tourist Burma?

In 1980, the only communication to Yangon was by overseas telephone, telex and cable. The quickest way was to “talk” on the telex line as booking an overseas phone line to and from Yangon took hours and the connection was very bad. I made an agreement with a telex operator at TB that I would connect by telex at 6pm everyday.

I sent all the inquires by telex in the morning then there’d be a ‘ting! ting!’ on the line at 6pm and I would “talk” with the sales/operations manager. Although expensive, it meant I got all my answers and information and gave all the information to the Thai tour operators and everyone was happy. Burma was on the market again, and Thai operators put tours to Burma back in their brochures.

I imagine that communications wasn’t the only challenge. What were some of the other difficulties you faced?

We had to prepay for tour services to TB. But Thailand also had strict rules for foreign exchange transfers. We could not buy a bank draft from the Thai banks because of foreign exchange controls so we had to order bank drafts from moneychangers at high rates.

The moneychangers could bring in a bank draft from Hong Kong within 48 hours. We then had to rush to Don Muang Airport and give the bank draft to the UB [Burma Airways] cabin crew, who would take it and deliver it to a waiting representative from TB at Mingaladon Airport. We had to pay 200 baht to the UB airhostess for every envelope with a bank draft but if the bank draft didn’t arrive on time, TB would not receive our clients!

There were also costing challenges. Every year we had to guess the net tour cost to be paid to TB.

Young dancers prepare for a Myanmar New Year performance in Yangon in April 1980. (AFP)

Our selling rates were based on TB net cost rates, which they published only in September. This was the wrong time because we had to give our net contract price to the tour operators by June every year as they needed to print their brochures in time for the travel trade fairs and to distribute to their agents.

Fortunately we normally made a profit – except in one case with a UK budget tour operator. For every person they booked we lost $100 per person because we quoted a low price in June during low season that didn’t take into account the very high tariff from TB in September. We had to pray that they would not book any clients but they sold about 8 to 10 packages every year!

The quality of service in Myanmar in those days wast. What were some of the complaints you received from clients?

The hotels were run down, with bad service and terrible food. All had rats, termites under their beds and cockroaches everywhere. When the Gems Emporium was held annually at Inya Lake Hotel, all tourists in Yangon were pushed out to Bagan or Mandalay unceremoniously.

When selling our packages we would include one complimentary dinner at Mandalay Restaurant on Sukhumvit Soi 13 in Bangkok to give clients their first taste of Burmese cuisine before going to Burma.

This turned out to be the best meal of their trip – the tourists came back complaining about the meals, which were all at government hotels. It was always clear vegetable soup, sauteed cabbage and either fish or chicken curry, right throughout the trip!

How about transport around the country?

The top agents from Europe using domestic air travel and that was a perpetual tribulation for all concerned. UB ran domestic flights using Fokker F27 props with 40 seats, of which two seats were occupied by security officers and the remaining 38 seats for government VIPs, tourists and locals – in that order.

The group bookings were maximum 30 people per flight and the big operators booked their packages one year in advance. These were always confirmed by TB. But when the time came to travel, they were always bumped from the flight, especially the Yangon-Bagan sector because of government VIPs.

Those bounced off the flight had to travel from Yangon to Thazi by train – ordinary class, with hard wooden seats – and then Thazi to Bagan by TB BM [mini buses] with wooden seats and no air-con!

Yangon residents crowd onto a World War II-era bus in 1983. (AFP)

The VIP clients and operators complained vigorously every year but kept coming back to Burma because it’s such a beautiful destination.

The agents demanded a refund for the sector if they had to travel by train and bus, but TB always replied we were lucky not to be charged extra as a fuel surcharge because the petrol cost was higher than if they’d gone by flight! How could we explain that to the agents? To pacify them and to maintain the relationship we refunded $10 per person out of our pocket.

Was it all tour groups at that time, or were there individual travellers too?

There were many FITs [free independent travellers] at that time and they travelled from Yangon to Thazi by train ordinary class and then Thazi to Kyaukpadaung by public buses – sometimes on the roof! From Kyaukpadaung to Bagan they would take another public bus and then from the bus stop to the hotels by trishaws.

It was quite a trip but there was no other choice. We introduced a special FIT program – Yangon to Thazi by train, Thazi to Bagan by chartered Toyota Hilux pickups – that was very popular. But we received strong complaints from the trishaw men in Bagan, as no more people were hiring them to go from the bus stop to the hotels because of our FIT programs.

What was your most memorable incident?

Well, our most anxious moment was in 1983, when North Korea bombed the Martyrs’ Mausoleum in Yangon. We had 35 members from the Siam Society Bangkok checked in for a UB Flight to Yangon.

While they were in the transit lounge waiting for departure, news of the bombing came on the radio. They were 50/50 whether to go or not but fortunately all members decided to go to Yangon. If they didn’t, we would have had to refund all of them and it would have bankrupted us.

You continued to send tour groups to Myanmar after the 1988 coup. How did the business change under the new government?

One big change was in 1989, when the military government changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar. I went to ITB Berlin in March and spent the whole five days explaining why the name had changed. After hard work over the years tour operators printed Myanmar (Burma) in the brochure because Myanmar was still an unknown name around the world. Tourist Burma became Myanmar Travel and Tours (MTT).

There was also the tourist visa application fiasco. The problem started when many negative articles written by journalists as well as travellers irked the military government. New rules came out: all tourist visa applications must be submitted through tour operators or agents, who must guarantee the applicant is not a journalist.

In passports the occupation is never mentioned so we checked the countries they had visited. If they had visited Pakistan, the visa mentioned the applicant was a journalist and therefore we had to reject them.

Otherwise, there was no way to check and we just prayed there were no journalists or tourists-turned-journalists who wrote negative things about their trip after they got home! Some did and we had to explain why we didn’t know. We received strong warnings from MTT and the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok.

We had an unforgettable experience in 1992 when we managed to arrange the visit of the MS Ocean Pearl cruise ship with more than 300 people. It berthed at Sule 4 wharf and it was a big achievement to bring the ship in, which we managed to do through high-level Navy contacts at the Port Authority.

MTT arranged for tourist visas on arrival – after two days, immigration officers were still chopping passports on the ship and just managed to complete them before departure.

It was an unforgettable sight to see the cruise ship at port and tourists walking down the gangway – an exciting time for all. The main attraction was four new air-conditioned Hino buses that had just arrived for the tourists. They were the first air-conditioned buses in Yangon!

You returned to Yangon in 1994, but have remained active in the tourism and hospitality industry, running Padonmar restaurant for the past 17 years. What’s your view on the changes within the industry since then and where do you think it is heading in the next five or 10 years?

There have been big changes because of fax and then computers – life has become very easy in the tourism industry. Over the years I became fully involved with a Myanmar restaurant and rattan furniture export business, so I let the young people take over the tourism business. Today I’m only involved in offering healthy, MSG-free, authentic Myanmar cuisine to tourists and visitors.

The tourism industry in Myanmar has suffered from high hotel rates and high domestic flight rates but it survived and thrived because of the extraordinary historical structures and beauty of the country.

For the next five to 10 years, the industry will continue to grow but the mentality and mindset of the Myanmar people must change as well. Our people are now travelling overseas so this should open their eyes – they need to copy the good habits they see elsewhere, such as not throwing rubbish on the streets and not spitting betel nut juice.

Any final words?

I’d like to thank all of those who helped me to promote Myanmar (and Burma) in the global tourism market. The list is very long.

But I would like to say a big special thanks to my Godfather, Captain “KT” Kyaw Thein Lwin from the merchant marine. He pulled me out of my job with Air France in Rangoon, sailed me away from Moulmein to Singapore and then helped me land in Bangkok.

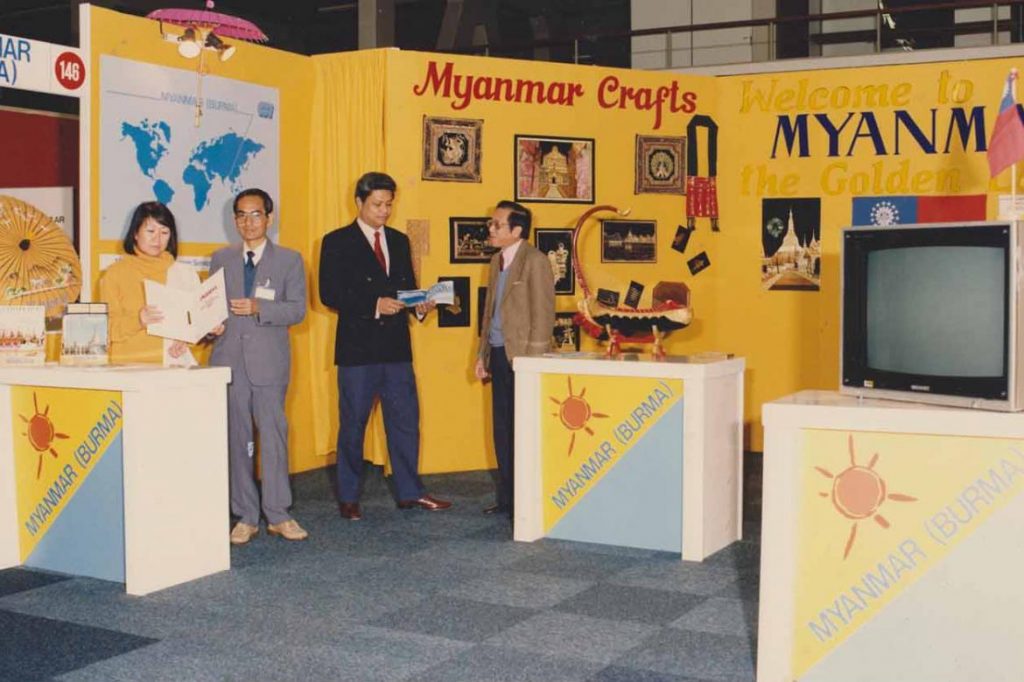

This article originally appeared as part of Discover Myanmar, Frontier’s special report on the tourism industry. Top photo: U Sonny Aung Khin, second right, at a Myanmar booth at a travel exhibition in Amsterdam in 1990, together with U Myo Lwin, the general manager of state-run Myanmar Travels and Tours, U Kyaw Kyaw from MTT and Marie Wynn, a Paris-based sales executive of Burma Cultural Tours. (Supplied)