The Central Bank is steering the bank lending model away from overdraft loans with immovable assets as collateral in order to make financing more widely available.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

IN THE 20 years U Min Naing has been running his company, Doh Pyi Thit, he has never taken a loan from a bank. His is not a small business; Doh Pyi Thit has built railways, large buildings and operated mines.

“When I started the company I just used my own money to cover all operations,” he said. If he needed more, he borrowed it from his family, or business partners.

Then, several months ago he came across an opportunity to buy a tungsten mine in Tanintharyi Region for K230 million (around US$180,000). He decided to take out a loan to fund the acquisition and approached two of Myanmar’s largest banks. However, Min Naing found to his surprise that he was unable to meet the collateral requirements.

Both banks asked him to pledge landed property as security. They said his house in Yangon, which is worth around K250 million, was unsuitable because he shares ownership. They also rejected several acres of valuable, but undeveloped, land in the industrial township of Hlaing Tharyar.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“This did not hurt me too much, as I can still run my business, even if I can’t expand it. But I learned that we cannot yet rely on the banking system for loans,” he said.

New prudential rules

It is precisely this problem that the Central Bank of Myanmar was trying to tackle when it released a set of modern prudential regulations in July 2017 under the new Financial Institutions Law.

The four regulations would eventually send shockwaves through the banking industry, but the response at first was muted; the banks seemed not to take the order seriously.

By September they realised the Central Bank was intent on seeing through its reforms and began warning that they would need more time. A key sticking point was a requirement that overdraft loans, which make up around 70 percent of all lending, be cleared by January 2018.

Following a meeting with bank representatives on October 2, the Central Bank issued a directive in November that pushed the deadline back, by allowing banks to convert their overdraft loans to term loans with a maximum maturity of three years.

They would also be required to reduce overdraft loans to a maximum of 50 percent of their portfolio by July 2018, 30 percent by July 2019 and 20 percent by July 2020.

Representatives of several banks pointed to the slowing economy when explaining that even these extended deadlines will be difficult to meet. Over the past two years, many of their clients have been unable to make interest payments on time, they say; if the loans had been term rather than overdraft, they may have been classified as non-performing.

“The Central Bank is pressuring banks to collect outstanding debt, but banks cannot squeeze businesspeople for money, because they know businesses are struggling,” said U Ye Min Oo, a member of the National League for Democracy’s Central Economic Committee.

In this challenging environment, non-performing loan ratios are rising. In the past, banks simply rolled over bad debt. Now, they cannot do this so easily, for two reasons. First, they must reduce the portion of overdraft loans on their books. Second, the Central Bank forbids them from converting non-performing overdraft facilities into loans.

Labourers work at a construction site in Yangon. The Central Bank’s mismanagement of the banking sector has diverted scarce financial resources into real estate speculation. (AFP)

While bankers declined to disclose their NPL ratios, they said they were increasing their reserves to offset the growing risk.

This is squeezing balance sheets, said U Than Lwin, a senior consultant to KBZ Bank, the country’s largest private bank.

“Banks are required to hold these reserves [two percent of the value of non-performing loans] at the Central Bank,” he said. “But to meet interest payments to depositors, the banks need to lend that money to businesses at a higher rate.”

A legacy of mismanagement

Such difficulties are a legacy of the mismanagement of the sector by the Central Bank and in particular a 2008 decision to restrict the maximum term length of a loan to 12 months and introduce stricter collateral requirements.

This encouraged banks to instead issue overdraft loans with repayment dates that could be continuously extended. It also dangerously intertwined the property and banking sectors.

To secure loans, businesses invested in property that could be used as collateral. This was fine when sales were brisk and prices rising, but with the property market in a downturn since 2015 they’ve been unable – or unwilling – to cash out and repay their debts. Because loans have been rolled over for so many years, it’s unclear how many are non-performing.

“Most of the loans are still tied up in the construction sector,” said U Myat Thin Aung, patron of the Hlaing Tharyar Industrial Zone Development Committee. “The property market is still frozen, so not only are they unable to pay back the loans, some can’t even pay interest. Because of this, banks have been unable to lend to other businesses.”

Mr Sean Turnell, a special economic adviser to the state counsellor, said the 2008 regulation was “the source of many of the current problems of the banking system”, as banks lent almost entirely on the basis of land as collateral.

“This favoured the already wealthy and connected, and had the extra effect of driving funds and capital into real estate. Accordingly, real estate prices soared, and Myanmar’s scarce financial resources were diverted into unproductive real estate speculation instead of productive activity. Myanmar’s farmers and entrepreneurs got little credit – property developers [got] an abundance.

“Meanwhile, high property values made cities like Yangon expensive places to do business, driving Myanmar’s competitiveness as a manufacturing centre down.”

The regulation also created the “very serious” problem of related-party lending – that is, the phenomenon of banks lending to entities associated in some way with that bank.

“The most significant funds went to the most significant conglomerates, which also happened to be the owners of banks for the most part,” Turnell said. “Overall, Myanmar was left with a financial system that was not conducive to what it needed to grow and development. And that was the biggest casualty of all.”

Risk-based lending

While the issue of overdraft lending has gained most attention, the key point of the July 2017 regulations was to shift bank lending away from short-term loans with immovable assets as collateral, to one where medium-term loans are issued based on a range of factors, including cash flow and business plans.

Writing in the Myanmar Times in late January, U San Thein, a former central banker and senior adviser to German development agency GIZ, said that under the present system banks were just like “pawn shops”.

“In contrast, under the risk-based, or cash-flow based system of lending, banks can take a more holistic approach when judging the weaknesses, strengths, viability, credit amount and particularly the repayment capacity of each business,” he said.

“When banks are more familiar with risk-based lending, longer term loans could be allowed to more effectively support the country’s SMEs.”

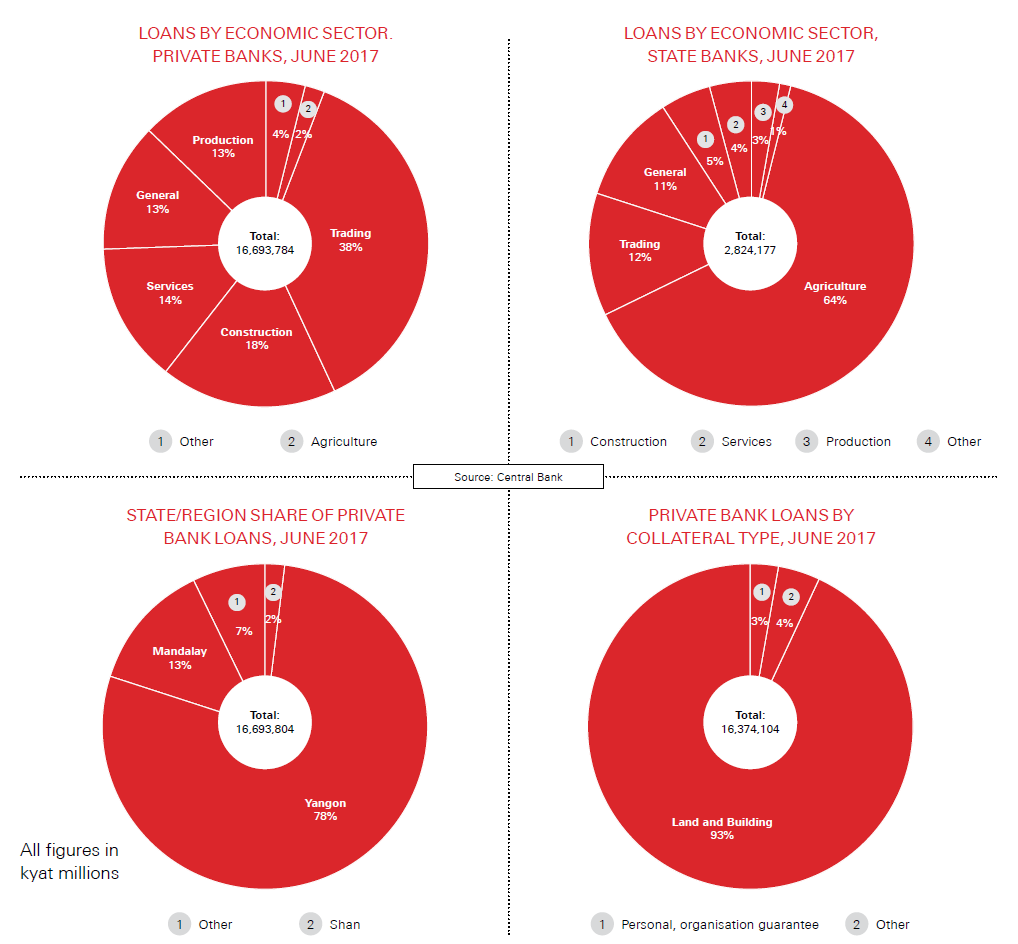

Figures from the Central Bank’s latest Quarterly Financial Statistics Bulletin highlight many of the issues facing private banks that the regulator is seeking to address. Ninety-three percent of loans are secured using land and property as collateral, while 78 percent of all loans go to businesses in Yangon. Just 0.2 percent of loans are going to SMEs.

The Central Bank is encouraging banks to become familiar with risk-based lending, through the development of new products with repayable terms that consider the business cycle and cash flow pattern of the borrower.

When lending to the agriculture sector, for example, banks could structure loans so that amortisation payments are lower during the planting season and higher when produce is harvested and sold.

typeof=

A question of rates

Ironically, the new Central Bank regulations have made the lending environment tougher in the short-term for many business but particularly SMEs, because banks are concerned about issuing loans to high-risk borrowers.

To help banks diversify their sources of collateral, the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group, is working with the Central Bank to develop a law on moveable asset finance.

This would enable companies to use physical property to access loans. “If we can draw up that law, companies will able to use movable assets – from vehicles, to jewellery – as collateral,” said IFC country officer Daw Khin Thida Maw.

Legally, banks can already accept movable assets, but few are willing to take the risk. A law regulating the practice would provide security to both banks and borrowers.

The industrialist Myat Thin Aung says he also hopes to see the interest rates on bank loans fall. The Central Bank rate is 10 percent and there is a bank deposit rate floor of 8pc. This means that banks lend to almost all companies at the lending rate cap of 13 percent.

MP Daw Thet Thet Khine (NLD, Dagon), who is also a member of the Pyithu Hluttaw’s Banks and Monetary Affairs Development Committee, suggested to parliament on January 25 that the Central Bank could cut interest rates for both savings and loans.

If the Central Bank moved the deposit floor to 7 percent and the lending cap to 11 percent, it would drive economic growth and help create job opportunities, she said.

But private banks would be likely to resist such a move. They have called for an increase in the lending cap, to enable them to price loans to risky borrowers, such as SMEs.

The need for a more liberal interest rate environment became clear to U Than Tun, a former chair of the Small and Medium Industrial Development Bank (SMIDB), when the bank participated in a two-step loan scheme, aimed at giving more loans to SMEs.

In the latter years of the Thein Sein government, the Japan International Cooperation Agency introduced the scheme, in which banks borrowed at 13 percent and on-lent the money to small businesses after adding another 3 or 4 percent.

SMIDB borrowed K10 billion to lend to SMEs. “We got back less than K6 billion,” he said.

Another possible solution being floated is to allow foreign banks to lend to local companies. For now, the 13 international banks operating in Myanmar can only lend to foreign businesses and local-international joint ventures.

U Soe Myint, chair of the Myanmar Garment Manufacturers Association, said that without access to alternative sources of credit, “Our economy will not able to recover. We need longer-term financing, which can only be provided by foreign banks.”

Missing bodies

The key to the impasse, say banking experts, is the formation of new bodies relating to bank lending. Above all, they say, Myanmar needs a Credit Bureau to collect information about the credit-worthiness of potential borrowers.

Slow progress is being made on this front. The Myanmar Banks Association signed an agreement with Singapore’s NSP Holdings in 2014, then had to wait for the government to pass the Financial Institutions Law and enact a regulatory framework.

Now, the IFC is training Central Bank staff in the skills needed to run a Credit Bureau, but the office has not yet been licenced. Until it is, banks will struggle to perform due diligence and are likely to continue to rely on fixed collateral to protect themselves against the risk of default.

Meanwhile, as banks begin the long journey towards compliance with the new regulations, businesses are being hurt by the slowdown in credit. The Central Bank needs to take this into account, said U Nyan Thit Hlaing, a secretary of Myanmar Construction Entrepreneurs Association.

Ye Min Oo, the economic adviser to the NLD, said the Central Bank should have consulted with stakeholders in the banking sector and the business community.

“We are not blaming [the Central Bank] for issuing the rules, but for the way they kept discussions to themselves and for the timing, which does not reflect the economic policy of the government,” he said.

Despite the criticism, Turnell said the regulations were still necessary for improving financial inclusion and moving away from a system that “favoured existing elites”.

“[At the moment] If you are a new business, maybe just someone with a great business idea, you have no way of getting credit, no way of getting capital – unless you already own significant property.”