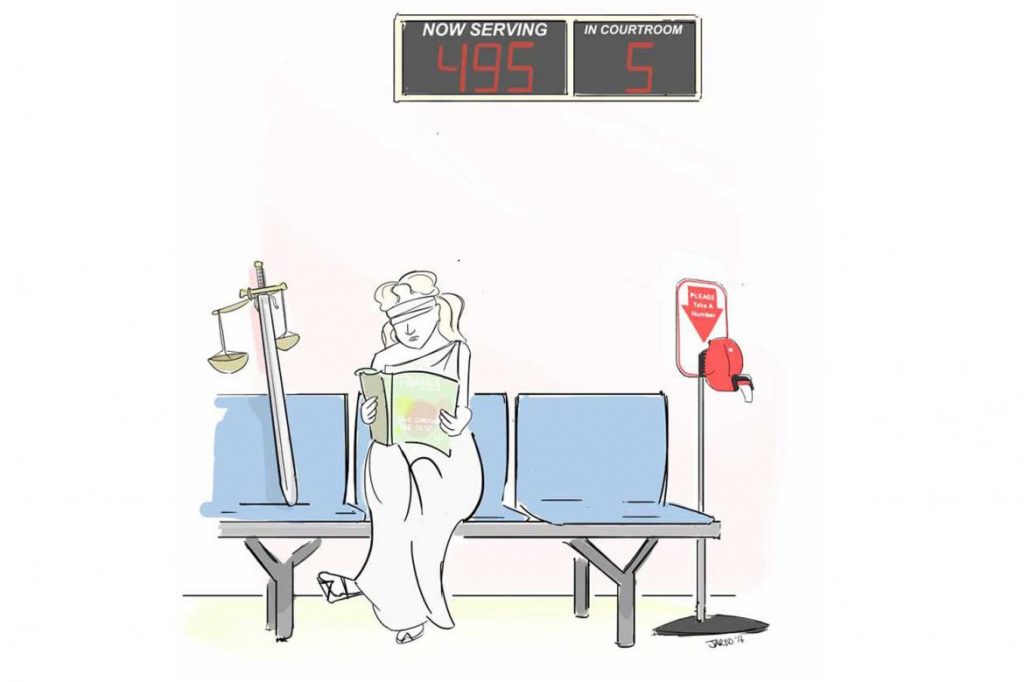

Nobody should have to spend more than two years on remand, waiting for their day in court.

SEVEN HUNDRED and eighty-nine days.

That is how long Mr Niranjan Rasalingham and his three co-defendants have been in detention since their arrest for alleged credit card fraud in late 2014. They still have not been charged – in fact, their trials have barely progressed at all.

If ever there was a case that highlighted the need for reform to Myanmar’s legal system and its processes, it is this one.

As the trials are sub judice, it is not appropriate for Frontier to comment on whether they are being conducted fairly. Nor are we able to assess the allegations levelled by at least one the defendants that police failed to uphold his rights while in detention, or that a private company was involved in his interrogation.

We certainly have no view on the guilt or innocence of the accused. That is for the court to decide.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

What we do have a view on is a simple principle: Nobody should have to spend more than two years on remand, waiting for their day in court.

The delays are so lengthy that if the four defendants had pleaded guilty at the start, they would likely have been released already, albeit with a sizeable fine.

But it is their right to plead not guilty; in that case, the prosecution is then required to produce evidence to prove their guilt beyond reasonable doubt. If the prosecution cannot, then the defendants in a case must be released.

The legal process should not extract guilty pleas from innocent parties simply because fighting charges would be too onerous.

An argument could be made that the delay in this case has been due, at least in part, to the defendants’ decision to apply to higher courts for the cases to be combined. Aside from the fact it is within their right to make this application, having cases of the same nature spread across eight township courts would have been logistically difficult.

Witnesses would need to appear in multiple courts to essentially give the same testimony, for example. But there are other factors, too, not least the inability of the legal system to provide adequate translation for the defendants.

The delays have generated further delays, not least because they have resulted in the defendants changing lawyers multiple times.

This is a question of fundamental rights. Section 14.3(c) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that everyone has the right “to be tried without undue delay”. Myanmar, along with a small number of other countries, has neither signed nor ratified the treaty.

But a government committed to the principles of justice and fairness should ensure that the legal system tries all cases in a reasonable manner, without interfering in the result.

The case at hand is serious, of course, particularly for the integrity of a banking system that is yet to win the trust of most of the people. As it is, there are many regular complaints about problems with the country’s ATM networks.

But that should not overshadow what we believe to be the crux of this issue. The trial of Rasalingham and his three co-accused is complex and there is little precedent for it in Myanmar. But the legal system has shown that it is unable to equitably hear cases of this nature.

As one lawyer noted in our investigation into the trial (see pages 20 to 23), the courts follow laws that are set by the legislature and lawmakers.

The parliamentary judicial affairs committees should conduct a prompt review of the case, examining why it has taken so long to conclude and what changes could be made to avoid a repeat of this sorry episode.

This editorial originally appeared in the January 17 edition of Frontier.