As junta forces increasingly refuse to return the bodies of those they’ve slain, the pain of grieving families is being exacerbated by uncertainty.

By FRONTIER

The morning of March 11 was surprisingly cold in Mandalay, at least by the normal standards of Myanmar’s second-largest city.

U Zaw Lin and his 19-year-old son, Ko Lin Htet, kept warm by huddling under a blanket. Lin Htet, a second-year geology student at Mandalay’s Yadanabon University, was recounting his experiences on the front lines of Mandalay’s anti-military protests when their conversation was interrupted by a phone call.

“I have to go, dad,” Lin Htet said after hanging up. He leapt from the bed, disappearing into another room to get dressed.

When he returned, he was wearing his father’s white sport shoes. “Look, your trainers fit me. Can I wear them?” Zaw Lin, 47, recalls his son asking.

Lin Htet wanted to wear the shoes because he planned to join the Mya Taung protest group, which has been marching twice-daily through Mandalay since shortly after the February 1 coup. Sensing his son’s excitement, Zaw Lin gave his assent.

Then they went their separate ways: Lin Htet to the protests, Zaw Lwin to his job at a car spraying workshop on Mandalay’s 16th street in Maha Aung Myay Township.

He was at home eating lunch when he got the phone call.

“A friend said that news was being shared on Facebook that Lin Htet had been shot,” Zaw Lin recalled, his voice trembling. “I was shocked – I couldn’t believe it at all.”

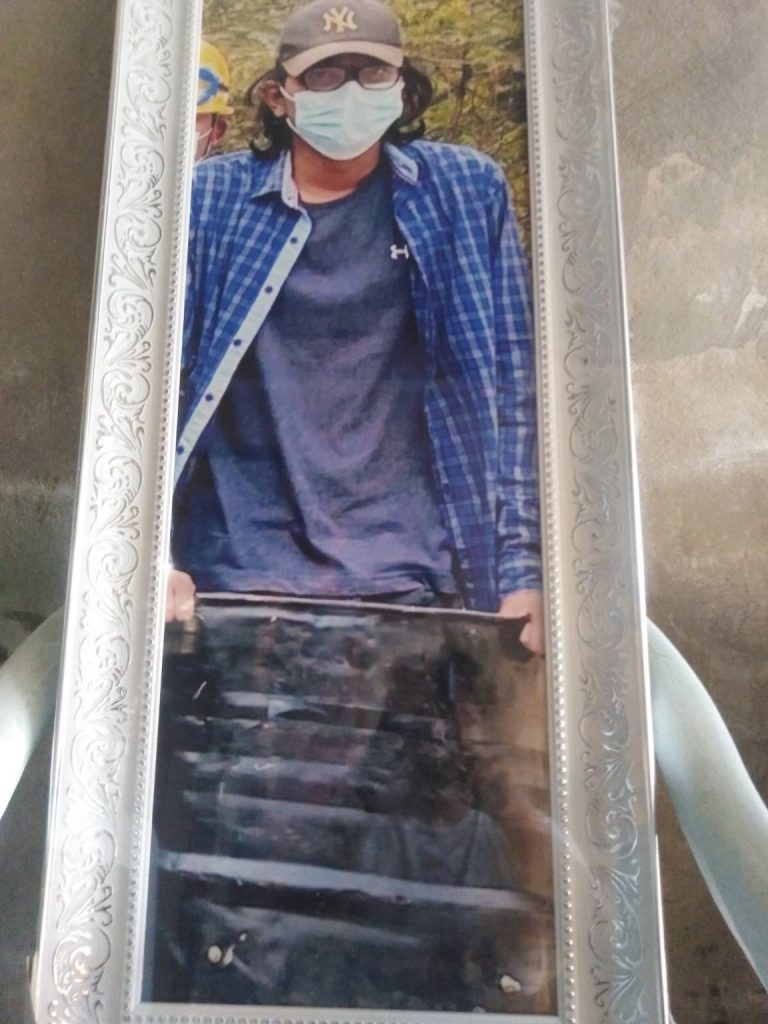

As soon as Zaw Lin saw the photos, he knew it was his son. Lin Htet was tall, standing at six foot one (about 185 centimetres), with long black hair and the blue plaid shirt he’d left home in. What stood out in the photos, though, were Zaw Lin’s white shoes.

“When I saw the photos on Facebook, I knew it was my beloved son, but I had trouble believing it – I couldn’t breathe, I was in shock,” Zaw Lin said.

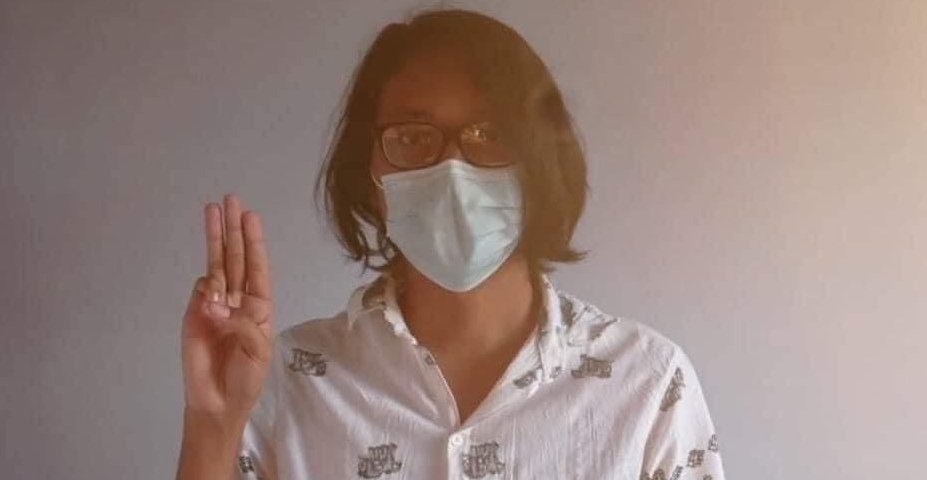

Lin Htet receives an award for academic achievement.

Lin Htet shortly before being killed by the Tatmadaw.

He rushed to the spot where his son had been shot, on 89th Street in Chan Aye Thar San Township, but the body was already gone. All that remained was the facemask his son had worn.

Witnesses told him they had seen soldiers drag Lin Htet’s body into an unmarked black Toyota Alphard and drive away.

Zaw Lin and his wife, Daw Htay Htay Myint, went to several police stations, army camps and hospitals around the city hoping to find their son’s body, but to no avail. Two days later, Police Chief U Toe Toe from the Maha Aung Myay’s No 6 police station told them that their son had been cremated the day he died.

“I asked, ‘Why weren’t we informed?’ When I asked how they could do that without telling family members, he said they had to do it because it was their duty,” Zaw Lin said.

He was furious at the police, both for their failure to help and their lack of remorse.

“If they were unarmed, I would have fought them one by one,” he told Frontier on April 6. “But at the time, I even had to apologise to them just so I could try to get back my son’s remains for burial. Still, they shouted at us and claimed they had no responsibility to help.”

More than a month later, Zaw Lin still does not know where his son’s remains are.

Myanmar’s security forces have responded with growing brutality to the anti-coup demonstrations that have swept the country in recent months, a movement dubbed by some as the “Spring Revolution” and largely led by youthful “Generation Z” protesters like Lin Htet.

Like Zaw Lin, scores of relatives who have lost loved ones face the added pain of not knowing the fate of their remains, and not having the chance to properly bid them farewell.

On March 17, six days after Zaw Lin lost his only son, Ma Yee Mon Theint’s husband was killed in Hlaing Tharyar, an industrial suburb in Yangon’s west. Ko Thura Oo, a 25-year-old trishaw driver, was shot and killed by soldiers and police during an afternoon demonstration on Tharaphi Street in the Shwe Lin Ban Industrial Zone.

Yee Mon Theint received the devastating news that evening, shortly after returning home from her job selling fish in a local market.

“I was told by a friend who ran from the spot where my husband was shot. I tried to go to him, but because of the continuous shooting I couldn’t leave [my home] immediately. When I got there, my husband’s body was gone,” she said, crying.

A witness told Frontier they saw Thura Oo shot in the head and back, before soldiers removed his shirt and hat and dragged his body into a nearby car.

Yee Mon Theint said that when she arrived at the blood-stained spot where her husband had fallen, all that remained were his shirt and hat. Desperate to find her husband’s body, she went to Hlaing Tharyar Hospital, but they had no record of him. Later, ahe heard a rumour that his body had been dumped in a creek in the industrial zone, but her searches turned up nothing.

Despite not finding his body, Yee Mon Theint accepted her husband’s death and held a small funeral ceremony three days later, but she still hopes that his remains will one day be returned.

“Although my husband is already dead, I really want his body back. I want to bury him in a peaceful place,” she said, wiping away tears. “I have no idea where they took him.”

Estimates on the number of people killed in Hlaing Tharyar range from 70 to more than 100. The leader of a relief organisation that works in the township told Frontier that the remains of at least 12 people who have been confirmed dead have not been returned.

“Some family members are missing dead bodies although they heard information from witnesses, or [had seen evidence] that their sons and husbands had been shot during the protests,” said the leader, who asked not to be named.

In other cases, he said, his organisation has retrieved the bodies of protesters who have been killed, but has been unable to locate any family members, or even identify them.

A relief worker in Mandalay, where at least 118 people have so far died, told Frontier that the bodies of three people – Lin Htet, another man and a woman named Daw Pyone – were unaccounted for in Maha Aung Myay Township alone.

Relief groups are often asked to help families try to locate missing family members, the official said.

“If the person’s body is not with the relief group, the family members then go to a police station or hospital to try and confirm if the person is alive,” he said.

While the Mandalay relief worker said he couldn’t understand why security forces were not returning the bodies of those killed in the crackdown, the leader of the Hlaing Tharyar relief group said he believed the military was trying to cover up evidence of its brutality.

“I think it’s simply that the military wants to destroy the evidence of what they are doing,” he said. “They don’t want to hand back bodies that clearly show evidence of being shot.”

The military regime has disputed death toll figures from independent monitoring groups, such as the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners. On April 9, the military regime claimed that just 248 protesters had died, less than half of the AAPP total. That same day, junta forces reportedly massacred at least 82 people in the town of Bago, and AAPP says as of April 18, 730 people had been killed since February 1.

Zaw Lin can still barely believe his son is gone. The father and son had enjoyed a close relationship, and Zaw Lin said he missed their animated conversations.

“We have been distraught since my son left. I only had one son; he was a very talented child, and I miss him so much,” Zaw Lin said, crying.

He described his son as intelligent, with a cool and calm demeanor, but said he had become angry after the February 1 coup. Lin Htet read news obsessively on social media; some days, he would sit alone and talk to himself, his father said, an indication of the profound impact the political situation was having on his son’s mental wellbeing.

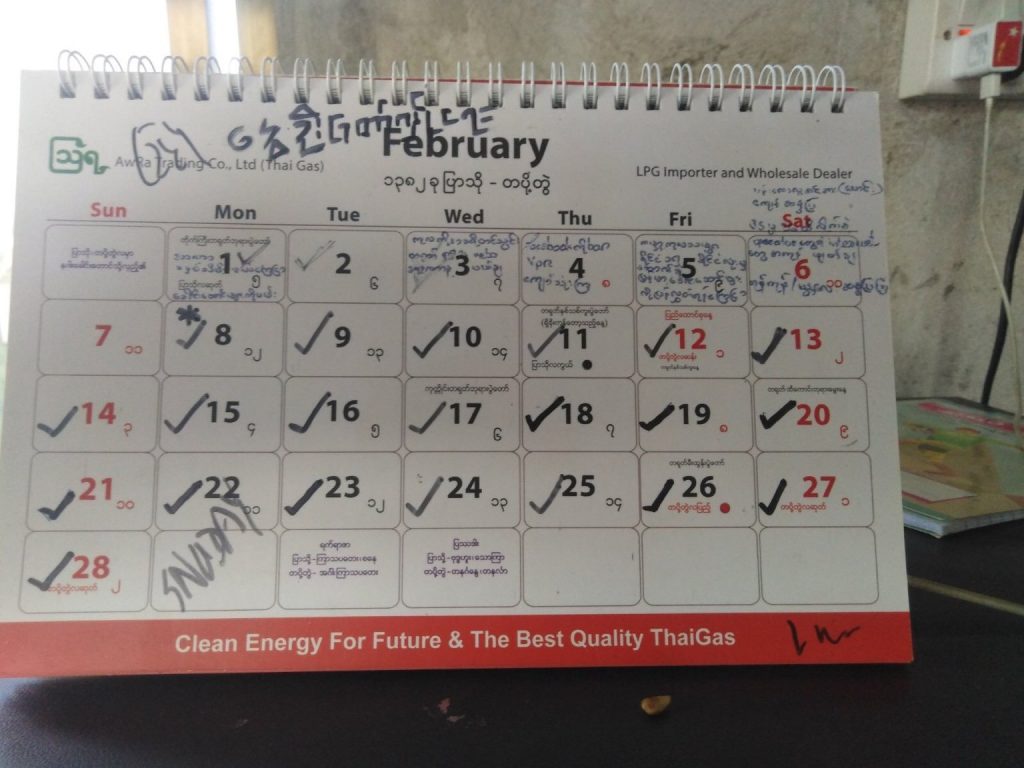

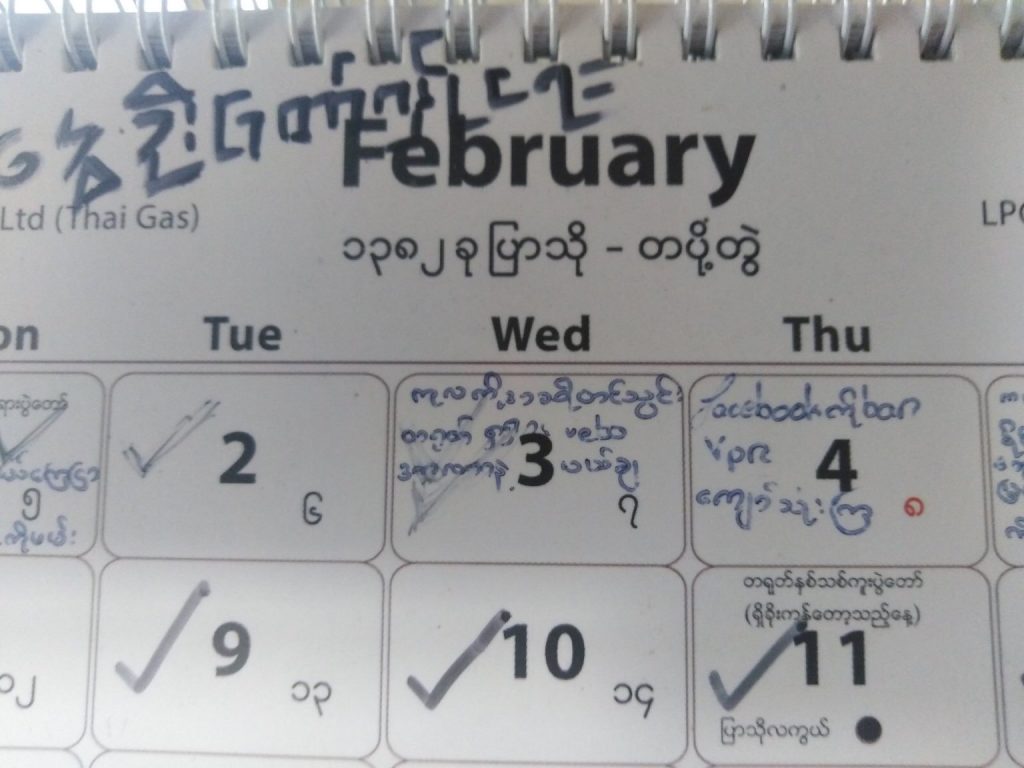

But Lin Htet had also been heavily involved in the youth-led protest movement since shortly after the coup. He would join rallies and marches, and note down significant dates – such as when protests started in Yangon and Mandalay, and when the United Nations held a meeting to discuss the situation in Myanmar – on a calendar at home.

Lin Htet had been marking important dates in the anti-coup movement down on a calendar at his home.

When Lin Htet’s parents tried to explain how anxious they were about him joining demonstrations, he would respond passionately, explaining why it was important for him to take part.

“I didn’t think he would be so interested in politics,” Zaw Lin said. “When I suggested that politics is not a simple topic and he should spend some time learning more about it, he responded that the time had come for the younger generation to take the lead, and that he needed to be involved.”

Zaw Lin accepts that his son is gone – but his wife, Htay Htay Myint, believes that her boy is still alive and in hiding. She prays and performs good deeds each day, hoping this will speed his return.

“Every day I have to live with anxiety and grief,” she said. “I still expect to get a call from my son, and wonder if someone with good spirits is protecting him. Until I find his body, I cannot accept that my son is dead.”