As Myanmar changes, some things stay the same for women.

by OLIVER SLOW & NOE NOE AUNG | FRONTIER

A few months ago, Ma Win, 23, was travelling to work in the window seat of a bus when a man sat next to her, covered the aisle seat with a bag to block the view of other commuters and began masturbating while staring her in the face.

“He was making sure I saw it,” Ma Win said. “I was in shock. I didn’t know what to do, so I just moved to another seat. I still remember that I was shaking,” she said.

Her friend, Ma Nilar, also 23, had a similar experience. She was taking a shortcut to a bus stop in Yankin Township when she walked past a man urinating on the side of the road. When the man saw her, he displayed his penis and began shouting obscenities.

“I shouted at him to go away and held my umbrella as a weapon and it worked,” Ma Nilar said. “But later I thought that I should have taken his photo and made a complaint at a police station,” she said.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Ma Win said she also regretted taking no action, such as not alerting other commuters.

When she discussed the incident later with a senior colleague, the woman said it was because she looked cheap and flirtatious.

“I felt guilty and unhappy about myself at first, but later I realised that I was blaming myself for a man’s dirtiness. This is a completely unacceptable mindset,” Ma Win said.

Many of the women interviewed for this article said sexual harassment on the streets or in public transport was a regular occurrence. Many young women say they have experienced harassment in one form or another, but most did not lodge a complaint because they thought it would be a waste of time.

“Here in Yangon, having your body touched by male bus attendants is an ordinary thing. Only a few people regard it as sexual harassment and many men do not think that what they are doing is inappropriate,” said Ma Win.

It’s an opinion that resonated with Ma Lei Lei, 21, who was touched on the thigh by her 50-year-old private tutor during a class in the Karen State capital, Hpa-an.

“I didn’t know it was sexual harassment at the time, because I didn’t have enough knowledge and because he was my teacher,” said Ma Lei Lei. “I was quite confused and really unhappy with his behaviour and didn’t know how to escape. According to our country’s culture, we have high respect for teachers, so I didn’t dare say anything against him. I couldn’t even talk about it with my parents,” she said.

Apart from sexual harassment in public, other forms of gender-based abuse include economic, emotional and physical violence, which often occurs in homes.

About 35 percent of the world’s women experience sexual violence from either their partners or strangers during their lives, various studies show. A study by the World Health Organisation shows that about 30 percent of women in relationships report having experienced physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner.

In Myanmar, data scarcity on the issue remains a challenge. A country-wide report by the Myanmar National Committee for Women’s Affairs said that between four percent and 21 percent of women reported experiencing mental violence while between three percent and 15 percent reported physical violence. Such varying figures show that little research has been done on the issue and real numbers are likely to be much higher due to underreporting.

“Men get close to me and they touch me with their penises from behind my back. Almost every woman who rides on the bus face this kind of situation.”

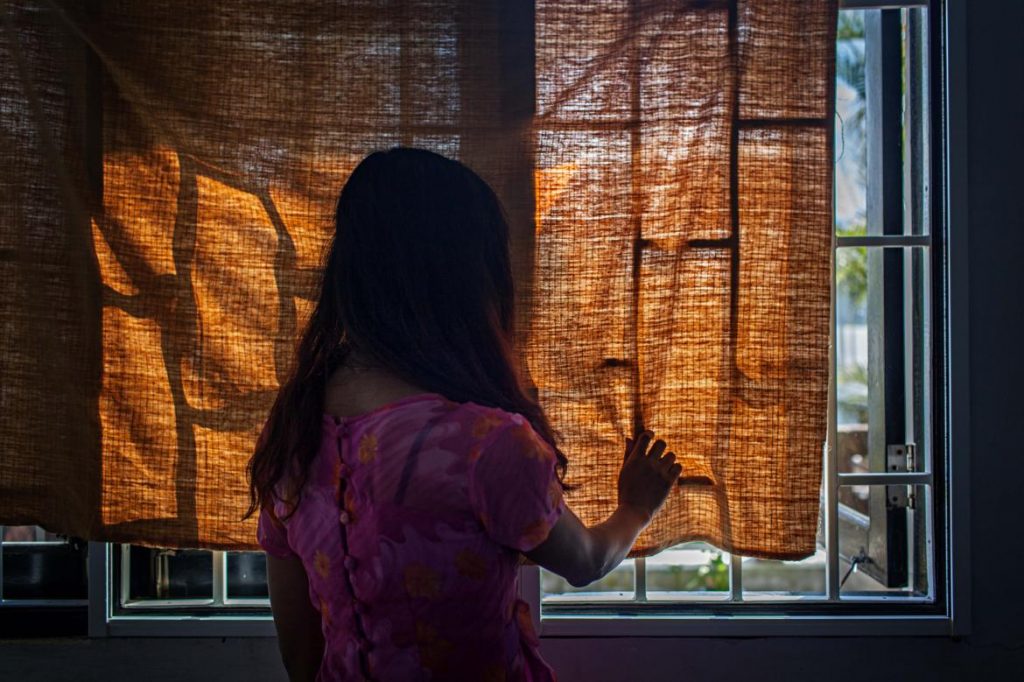

Myanmar women are sometimes targeted while riding public transport. (Lauren DeCicca / Frontier)

Violence in the home

In February, the Gender Equality Network released a report titled ‘Behind the Silence: Violence against women and their resilience (Myanmar)’, which looked at gender-based violence.

The report was based on interviews with 38 women in Yangon and Mawlamyine who had experienced some form of violence from their partner.

More than half the interviewees had experienced sexual violence or marital rape. “This was closely related to men’s sexual entitlement, or beliefs that a husband can demand sex whenever he wants,” the report said.

All of the women who reported non-consensual sex also experienced emotional or physical violence. Most of the woman had been subjected to more than one violent incident by their partner.

Groping in public places was also considered a normal part of the women’s lives, with incidents on buses in Yangon being particularly prevalent.

“Men get close to me and they touch me with their penises from behind my back,” said one of the interviewees. “Almost every woman who rides on the bus face this kind of situation,” she said, adding that the perpetrators were nearly always strangers, and sometimes bus conductors or drivers.

The report found that men having difficulty adjusting to stressful or challenging situations, such as pregnancy or unemployment, were often abusive towards their wives. Husbands’ affairs were reported by more than half the women as a trigger for violence. Alcohol was also a major factor in reported incidents.

The report found that community responses to violence against women were contradictory. Although some individuals support abused women, underlying community beliefs – such as pressure to remain in a relationship for the sake of children – often prevents women from taking steps to end the abuse.

One of the main forms of abuse described in the report was sexual violence in the home or marital rape. Women reported physical or verbal abuse if they refused to have sex with their husbands.. In some cases husbands refused to wear a condom during sex, despite knowing that they were HIV positive or had a sexually transmitted disease.

A key element in reports on sexual violence was the male notion of sexual entitlement, with husbands sometimes openly saying that it was their right to have sex with their wife. One pattern of abuse would involve a husband apologising immediately after the abuse had occurred, “followed by a period of quiet”. Inevitably, however, the abuse would continue.

One interviewee, a 32-year-old woman in Mawlamyine, said her husband had beaten her, injuring her ribs. Afterwards, she said, “He soothed me. At that time, he seemed like a different man. He would be kind to me for a day or two, then he would beat me again,” she said.

Lauren DeCicca / Frontier

Seeking solutions

Specialists working against gender-based violence have differing views on how to deal with the issue.

Dr Henri Myrttinen, head of the gender and peacebuilding team with the London-based anti-violence NGO International Alert, advocates an approach that involves men and includes what he calls “positive masculinities”.

“You need to bring men into these processes and also help them to see the benefits that they might accrue as men, by having less violence, by having the possibility of discussion about their own observations. So pushing that male power can actually be quite liberating,” Dr Myrttinen said.

He added that men who are violent towards women are often initially defensive, but the issue can be dealt with through thoughtful discussion.

“We talk about the issues they face as combatants, as people deployed away from their families, about stress disorder,” he said, as much of his work around the world involves military personnel. “So talking about gender but not naming it gender can sometimes be much more successful.”

In Myanmar, the NGO Colourful Girls was established in 2010 to raise the self-esteem and awareness of adolescent girls, who are often vulnerable to abuse. The organisation works in six of Myanmar’s 14 states and regions, running 25-week courses that teach participants about puberty, personal development, assertiveness and their own positive characteristics.

“We encourage the girls to express what they are feeling, to express their dreams,” said Ma Nant Thazin Min, the organisation’s chief co-ordinator. “The girls often have no trust in people to share their experiences and to express their feelings, so we create a place for them to do this, whether they are happy or sad.”

Ma Nant Thazin Min vehemently disagrees with the notion that there is gender equality in Myanmar, as some have claimed.

“Equal? No,” she said with a raised voice. “Totally not equal in every area. From the household to the state level, we do not have equality. People say things are changing, for example women can now go to beer stations or tea shops, but this is only visual. It is not a real change. What is important is changes in attitudes and behaviour.”

Women remain oppressed in society, Ma Nant Thazin Min said. If a woman is abused, she often does not know how to speak out and feels ashamed, she said, echoing the experience of Ma Lei Lei, who was touched inappropriately by her tutor.

“We need to create an environment for women to speak out about what they want and what they need,” said Ma Nant Thazin Min. “We are taught that we should not do this, not do that, but this kind of teaching needs to change. We need to encourage people to think for ourselves. We need to change ourselves [as women] in order to change our environment,” she said.

*Some names in this story have been changed. Title photo: “Win”, 23, from Yangon, was on the 86 Bus from Bo Galay Zay market in the morning when a man sat down next to her and began masturbating. (Lauren DeCicca / Frontier)