Members of Myanmar’s disabled community have been waiting since last year for the implementation of a law that gives them greater rights.

Words & Photos VICTORIA MILKO | FRONTIER

EARLY IN the morning, before the sun has appeared over the horizon, U Zaw Lin Htun waited at the bus stop in his bustling neighbourhood. People stopped to stare at him as they walked by.

When the bus arrived, two strangers took him by the elbows and guided him on to the vehicle. The other passengers craned their necks and stared as the bus driver instructed a woman to give Zaw Lin Htun her seat.

Further along the route, after asking the bus driver continuously for updates about where they were, Zaw Lin Htun was helped to alight from the bus by another two strangers. The easiest part of his commute was over.

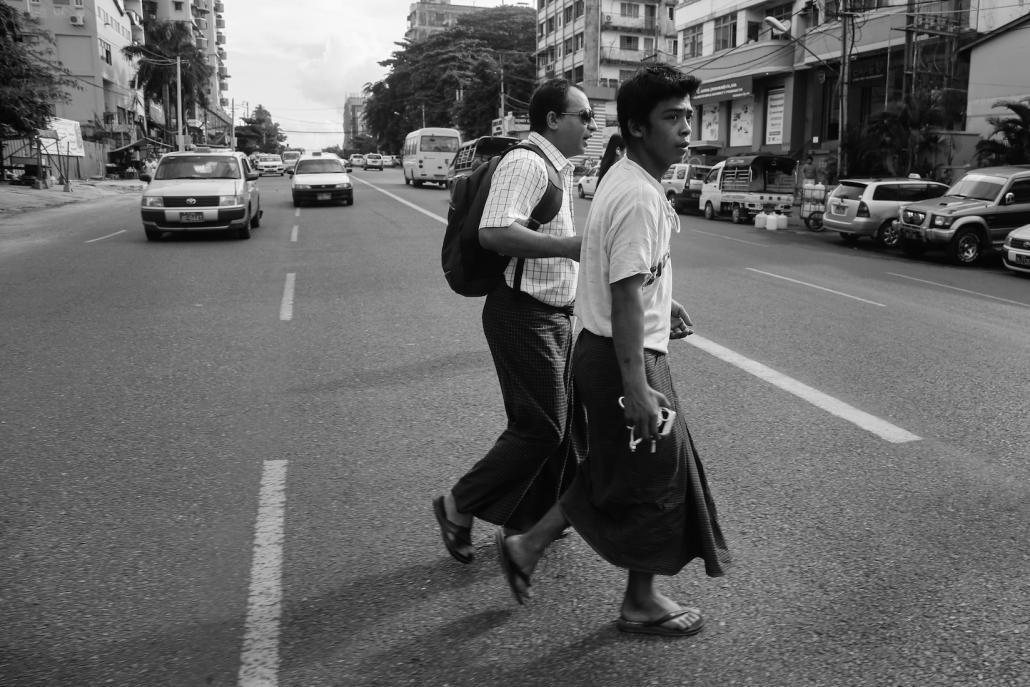

Using his walking stick, Zaw Lin Htun completed his journey by negotiating six lanes of traffic. There were no pedestrian crossings or traffic lights to help him. Even if there were, Zaw Lin Htun would not see them.

vmdisabledaccess-8.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Often riding packed buses across town to get to work, and unable to determine his location on his own, Zaw Lin Htun frequently asks the driver and fellow riders where he is. (Victoria Milko / Frontier)

Born with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disease that slowly causes a loss of vision, Zaw Lin Htun is legally blind. He relies on his hearing, a walking stick and the help of strangers to travel around Yangon.

According to data from the 2014 census, Zaw Lin Htun is one of an estimated 2.3 million people living with disabilities in Myanmar. They live with challenges on a family and economic level, laws that offer them little to no help or protection and a paucity of public infrastructure that would their lives easier, especially the blind and those confined to wheelchairs.

Zaw Lin Htun knows only too well how Myanmar’s infrastructure is a challenge for people living with disabilities.

“The sidewalk is not safe for me. There are too many obstacles; I can’t trust them,” he said.

Zaw Lin Htun’s arms and legs bear visible proof of his daily struggles – faint scars intersect fresh scabs from encounters with taxis, bits of metal, electric wires and debris on footpaths and in the streets.

Even seemingly simple tasks, such as paying for a rickshaw driver or bus fare, turn into a game of uncertainty and forced trust: The uniform size and shape of kyat notes provides no distinguishing marks among bills, leaving Zaw Lin Htun at the mercy of those to whom he hands money.

“When I pay someone, I can’t tell if I’m giving them enough or if they are giving me proper change,” he said. “It makes it even harder for me to manage public places or transportation.”

During the 150-metre (500-foot) walk from the bus stop to his office, Zaw Lin Htun walked into six cars, all parked haphazardly along the side of the road. Drivers in some of the cars scowled or yelled at him as he fumbled into their vehicles. Others rolled down their windows to stare at he walked by, tapping his walking stick back and forth, hoping to avoid a collision with another obstacle. But the most perilous part of Htun’s commute was far from over; he had to cross six lanes of traffic.

Salai Vanni Bawi, the program director for projects at the Myanmar Federation of Persons with Disabilities, has spent most of his life studying, advocating for and working with people with disabilities.

vmdisabledaccess-20.jpg

Zaw Lin Htun and his friend, a fellow member of the Myanmar Council of Persons with Disabilities, share a private moment during a workshop in Yangon. (Victoria Milko / Frontier)

“There are four different types of disabilities we must take into account; physical, mental, hearing and sight,” Bawi said. “All have struggles in Myanmar.”

In 2011, Myanmar ratified the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which puts disabilities and inclusive education within a human rights context.

But as late as last year, the disabled community had few, if any, safeguards for basic liberties. For example, Bawi said, government policies say that those unable to take care of their own affairs were not allowed to open a bank account, and those affected often include people with physical, hearing or sight disabilities.

“A new National Disability Right law was passed last year, but for implementation we need bylaws, rules and regulations shaped by policy,” Bawi said. “There are still many layers missing [for the law] to be effective.”

Bawi said that as the wait continued for bylaws to be drafted and enacted, disabled people and their families continue to face social and economic burdens.

vmdisabledaccess-22.jpg

Victoria Milko / Frontier

“The cultural norm in Myanmar usually has the family take care of the disabled person,” he said. “When one family member has to take care of that person that is one human resource that is used for that time instead of paid work. If the family didn’t have good enough finances to survive, it causes a huge impact and hardships.”

Last week, at a two-day training seminar led by Bawi, members of the disabled community, as well as activists and caretakers, spoke of concerns over the education sector as well.

“Teachers in our community will get impatient with disabled students,” a participant said. “They don’t care, and just give up on students.”

The lack of resources for those with disabilities can also take a social toll, further alienating those with disabilities from the general public.

Zaw Lin Htun said that although there’s beginning to be greater awareness among the public over the symbolism of his white walking stick, most of the people he encounters every day are unaware he is blind.

“Sometimes I ask people directions and they won’t answer me because they can’t tell that I’m blind when they first see me,” he said. “People tell me not to go out alone, but it costs too much to hire an assistant, so I mostly travel alone with my walking stick.”

vmdisabledaccess-15.jpg

Zaw Lin Htun relies on the help of strangers to cross busy streets. He says that strangers are often skeptical at first, not realising that he is blind. (Victoria Milko / Frontier)

Although Bawi praised the progress that the government has made during the last year in addressing the needs of the disabled, he said much remained to be done at the grassroots and bureaucratic levels.

“We need to study how society views people with disabilities,” Bawi said. “Then we will be able to understand how to fix the underlying problems and achieve something.”

As Zaw Lin Htun stood anxiously on the side of the busy six-lane road – the final obstacle between the bus stop and his office – a stranger approached, took hold of his elbows and guided him across the street to his final destination of his journey. As Zaw Lin Htun’s morning commute came to an end, he let out a sigh of relief, a smile creasing his face.

As Zaw Lin Htun was sliding off his shoes, folding his walking stick and stepping into his office, another blind man walked past, tapping his walking stick from side to side. He stopped beside the six-lane road and waited, no help in sight.