Widespread blackouts have returned to Yangon for the first time in several years. In recent weeks, many township-level electricity distribution offices have been forced to introduce scheduled outages to cope, with supply falling far below demand.

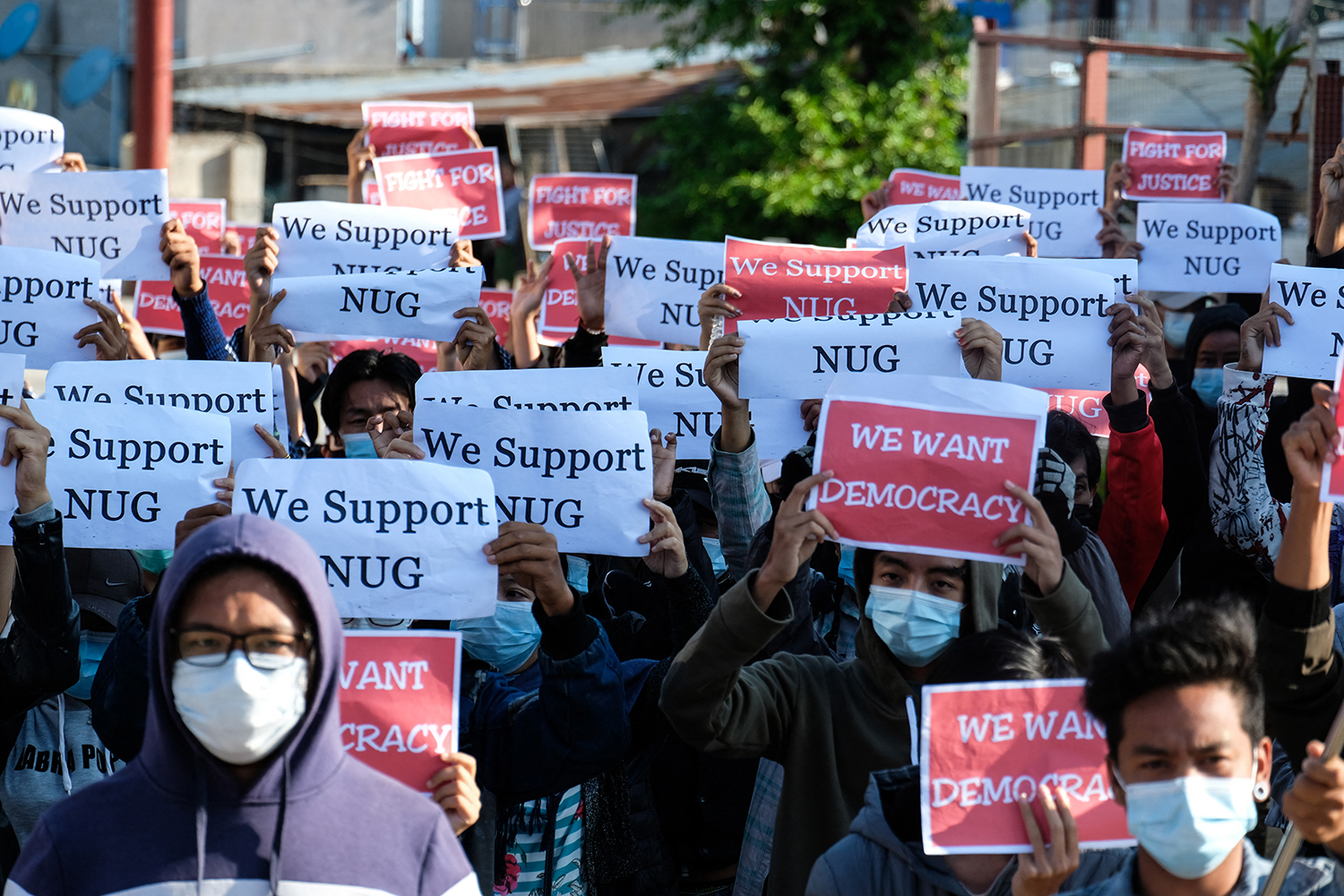

The ostensible reason is the lack of water in the country’s hydropower dams, which produce around half its electricity. But the real problem is the National League for Democracy government’s failure to bring enough new power generation capacity online.

In a few weeks or, at most, a couple of months, the monsoon rains will have begun to fill the dams and a fairly steady supply will return. But we should not let that distract from the huge power supply problem that Myanmar is facing. This year’s outages will seem mild compared to what we can expect in the next three to five years.

Since the NLD took office in March 2016, Myanmar has added barely any new generating capacity. The exception is the Myingyan gas-fired plant developed by Singaporean company Sembcorp. But in that case, most of the negotiations that enabled construction to take place occurred under the former Union Solidarity and Development Party administration. The NLD can claim very little credit, aside from not messing it up.

With new factories opening and millions of households being connected to the grid, demand is increasing at 10 to 15 percent a year. At that rate, Myanmar needs to add a plant the size of Myingyan every two years or so. But it can’t do this because it has precious little domestically produced gas to work with.

There is scope to get more out of existing infrastructure, by refurbishing hydro and gas-fired power plants and improving transmission and distribution systems. But that will only work for a short while. At some point, you need to begin generating more power.

The only major power projects that have received any sort of approval from the government since 2016 are four gas-fired plants (most of which would use imported gas) and a handful of small and medium-sized hydropower projects. None of the project documents issued so far are legally binding, and negotiations appear to be at a standstill. Crucially, none of the developers have yet been able to sign a power purchasing agreement.

The reasons for this are systemic rather than project-specific. The government wants to pay for power in kyat, but many of the costs associated with building power plants are in dollars. Power generation is a long-term game with relatively low returns. There’s little scope for developers to take on foreign currency risk of this kind. The government is also refusing to issue sovereign guarantees – basically, assurances from the government that it will pay power developers what it has promised. Finally, it is seeking the lowest possible price because power is heavily subsidised.

These are tricky issues and no one seems willing to budge. The government, though, needs to face the facts. It needs the power more than the developers need projects, and is going to have to find a way to accommodate some of their demands. There are several options, including raising electricity prices, which in their current low form are effectively a subsidy for the richest segment of society in the towns and cities connected to the grid. But it’s important that the government finds a way forward, and fast.

Too much time has already been wasted. Even if all of these projects signed PPAs tomorrow, we are still likely to face crippling shortages in the years ahead. A hydropower project usually takes at least six or seven years to develop; the proposed liquefied natural gas plants could come online faster, but would still require several years to get up and running.

There are faster options. Power imports or solar power generation could be set up relatively quickly. Stopgap measures, such as heavy fuel oil or even generators, could be considered. These are generally expensive and highly polluting, but would at least ensure a reasonable supply during the summer months.

Expensive power, though, is preferable to no power. Outages are an indication of managerial incompetence, of a failure to plan. Is that the message the NLD wants to send in an election year?