Myanmar’s English newspaper of record has outlasted the jailing of one of its founders for contrived offences, a suffocating censorship regime not lifted until 2012 and a controversial early connection with the junta. It may not outlast its current management.

By SEAN GLEESON | FRONTIER

THE NEWSPAPER lived long enough to vindicate its existence, a distinction not shared by many of its critics. It was mocked and denounced as a propaganda tool of the military regime, often by those who did not understand that it was as stifled by censorship as much as any other newspaper. Its cofounders were arrested; one, U Sonny Swe, spent eight years in some of the country’s worst prisons. After he was arrested in November 2004, Myanmar Times was forced to relinquish a controlling stake to a junta crony who hoped to use it as a springboard for an attempt at a parliamentary sinecure that ended in failure. Its employees were often harassed and intimidated by plainclothes police. Before pre-publication censorship was lifted in August 2012, its reports were mutilated by censor’s edicts as degrading as they were arbitrary.

And yet, when political reform finally came to Myanmar after decades of torpor, it was peerless. More than almost any other news outlet in the country, it was courageous enough to test the boundaries of what could be written on official malfeasance and human rights abuses after the government’s formal censorship apparatus was dismantled. It boasted some of the region’s finest reporters, who had trained on the job in the absence of formal media education and who managed to earn a suite of regional publishing awards. Their work was routinely cited in the international academic journals trying to make sense of the spellbinding pace of change in Myanmar. Despite a change of ownership and the transition from a weekly journal to a daily newspaper in 2015, it remained profitable and was the definitive English language news source for the elections that year.

Perhaps the Myanmar Times will reach those heights again, sometime in the distant future. It will require a reversal of fortunes as dramatic as the events of the past year, during which nearly two dozen foreign editorial staff have resigned or been sacked. They have left behind anxious Myanmar counterparts fearful of their jobs and despairing at the paper’s precipitous decline in quality. At the height of the battle between the newsroom and the board, staff routinely took to social media to air their grievances and to apologise for management edicts that blocked reporting on sensitive topics.

From obscurity and back

There was little to distinguish Mr Bill Tegjeu’s journalism career before his arrival in Yangon, according to a copy of his resume seen by Frontier. He spent eight years on the sports desk of the New Straits Times, a Malaysian daily disparaged by its critics as a mouthpiece for the Barisan Nasional parliamentary coalition that has ruled the country since independence. He took a break from the media industry for four years to manage a restaurant and pub at a beach resort. A six-year stint as a freelance sub-editor for the automotive magazine TopGear Malaysia was punctuated by a six-month spell as production editor of the now-defunct Malaysian Insider. According to a news report at the time, 30 people walked out to join a rival publication soon after he started there.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Despite never helming a daily newspaper in his 44 years in the industry, Tegjeu was backed for the top job by Dr Kim Song Tan, a Singapore-based board member of Myanmar Consolidated Media Co Ltd, which owns the Myanmar Times and its associated printing and publishing business. Tegjeu was given the title of editor-in-chief and responsibility for overseeing both the English language daily and the Myanmar weekly journal. His appointment was a surprise to editorial staff, most of whom did not know the position was being filled until a memorandum announcing his appointment was issued in early 2016.

According to company documents seen by Frontier, MCM was in reasonable financial health. The English daily was costing US$0.79 per dollar of revenue earned, while the Myanmar weekly and the society and culture magazine Now! had each incurred slight losses in the 11 months to November 2015. The three titles recorded a combined operating profit of just over $200,000 for the same period. Nonetheless, part of Tegjeu’s remit was reducing the paper’s operating costs, and a decision was made to rationalise parts of the English daily’s operation. As a first step, production and layout of the paper’s international section was outsourced to associates of Tegjeu in Malaysia.

Briton Mr Tony Child was appointed chief executive officer in October 2014, when the paper’s sole remaining founder, Mr Ross Dunkley, turned over the company’s day-to-day management. A little more than a year later, Child was beginning to realise that his position was untenable. He worked in an office opposite that of the new editor-in-chief in the paper’s sprawling headquarters on Bo Aung Kyaw Street. But the pair barely spoke in the three months they worked together; Tegjeu was hired without Child being consulted. In March, Child – who did not respond to a request for comment by Frontier – submitted his resignation, and the following month Tegjeu took on the additional role as CEO.

All the news that’s fit to print

It did not take long for Tegjeu to earn the epithet that would come to define his brief and turbulent tenure. Staff began privately referring to their new editor-in-chief as “Race and Religion Bill” – a reference to the legislative package enacted in the last year of the previous government. Just as the U Thein Sein administration yielded to pressure from the Buddhist nationalist movement, so would the Malaysian native come to be known to his subordinates as someone who yielded to the board’s directives to soften the paper’s coverage.

The disagreements were minor at first. Tegjeu would quibble with desk editors about the phrasing in certain articles and air concerns about the possibility of complaints against the paper. Editors would counter that articles were sourced properly and in accordance with their legal and ethical responsibilities as journalists. Soon these interventions stopped being framed as requests and started becoming demands.

Staff began blanching at the prospect of working under someone who was rarely in the office and whose only contact with the rest of the editorial team was to order the removal of reports on sensitive topics. It didn’t take long for the first editor to resign in disgust.

“I had a series of editorial tussles with Tegjeu, who essentially tried to muzzle our reporting to avoid controversy,” said Mr Guy Dinmore, the former head of the English edition’s news desk. “This situation was aggravated by his hiring policy, which appeared to favour incompetent acquaintances.”

The front entrance to the Myanmar Times office on Bo Aung Kyaw Street, in downtown Yangon. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Dinmore was hired in early 2015. A newspaper veteran, he came to Yangon after seven years as the Rome correspondent for the Financial Times. In his time at the Myanmar Times he earned the deep respect of his colleagues over his role in arranging its impressive coverage of the election in 2015.

The deterioration of his relationship with Tegjeu came to a head in May, soon after the paper ran a report on the Panama Papers – the huge trove of leaked information about companies registered in tax havens, sometimes for the purpose of money laundering and tax evasion. A total of 16 Myanmar names were on the Panama Papers list – including, apparently, the head of one of the country’s largest banks, who Dinmore said had refused requests for comment multiple times.

The story was published. The next day, Dinmore was ordered to print an apology to the bank chief.

“Tegjeu, who to be fair was acting under instructions from the owner of the Myanmar Times, at the time refused to put his name on the masthead so he was in effect an invisible presence as far as our readers were concerned,” Dinmore told Frontier. “His refusal to take responsibility or be held accountable for any of his actions led me to resign.”

A fortnight later, as production of the June 2 edition of the paper was being finalised, Tegjeu intervened again.

Earlier that day, an extraordinary press conference was held by U Kyaw Kyaw Oo, a member of the Myanmar Gems and Jewellery Entrepreneurs Association, concerning nearly $100 million that was missing from a gem industry fund. Kyaw Kyaw Oo claimed that former President U Thein Sein bore some responsibility for the missing cash. His account was backed by another official. Tegjeu demanded the removal of Thein Sein’s name from the report.

“Mr Tegjeu said he was afraid that if we printed the name we might be sued,” said an email circulated by a foreign staff member at the time. “We feel Mr Tegjeu’s decision has embarrassed the newspaper and damaged a reporter’s relationship to her sources.”

Privately, the editorial team discussed brokering a meeting directly with the board and demanding Tegjeu’s replacement.

“I see no way forward for anyone who cares about journalism with Bill in the building,” the same staff member wrote.

But Tegjeu was not ultimately responsible for the perilous position in which the paper’s editorial staff were finding themselves. Five days after the gems fund story was cut, Tegjeu’s name appeared on the Myanmar Times masthead for the first time, nearly six months after he joined the paper.

‘We value your ongoing readership’

It is clear that the attacks on border guard posts in northern Rakhine State last October, orchestrated by the Harakah al-Yaqin insurgent group and claiming several lives, have catalysed the greatest humanitarian catastrophe of the current government’s rule. More than 100,000 people have been displaced, overwhelmingly Rohingya Muslims, with more than 70,000 crossing the border into Bangladesh. Hundreds are feared murdered. Entire villages have been razed.

Elsewhere, it has also reopened a festering sore that has pitted much of this country’s population against their regional neighbours, foreigners living in Myanmar, and human rights advocates in the international community.

It would be wrong to say that the people of Myanmar speak with one voice on this issue. Nonetheless, the prevailing social climate permits the widely held and widely shared belief that, for instance, the Rohingya falsely claim to be the victims of abuses in order to gain international sympathy, or that paying attention to the persecution of the Rohingya is to the detriment of other serious rights abuses elsewhere in Myanmar.

The full spectrum of views on the Rohingya, from sympathy to antipathy, are on display in newsrooms throughout the country. Myanmar reporters are keenly aware of the risks that come with being associated with a media outlet seen as “pro-kalar” or “pro-Bengali” – the pejoratives that respectively describe anyone of South Asian heritage and the entrenched view that the Rohingya are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

typeof=

They face estrangement from their peers, an avalanche of online abuse, and occasionally threats to their life: an Amnesty International report in 2015 recounted the experience of a journalist who, in the middle of communal riots in Mandalay the year before, was chased by an armed mob who accused her of working for the “kalar media”.

It was still a deep shock to both Myanmar and expatriate members of the Myanmar Times newsroom when, a few weeks after last year’s crackdown began in Maungdaw Township, the paper’s special investigations editor was sacked for a report relaying claims that security forces had raped Rohingya women in Rakhine.

President’s Office spokesman U Zaw Htay and former Information Minister U Ye Htut both took to Facebook to attack the article by Ms Fiona MacGregor, who had worked for four years at the paper, covering the victims of ethnic conflicts and women’s issues.

A few days after her report was published, MacGregor was called to a meeting with Tegjeu and U Aung Saw Min, who had weeks earlier been appointed MCM’s chief operating officer after a long career at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MacGregor was told that she had brought the paper into disrepute and that her employment had been terminated.

The claims reported by MacGregor have since been substantiated in a report by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Based on interviews with some of the more than 70,000 people who fled to Bangladesh from Rakhine State, the February 3 report documented dozens of cases of gang rape and other sexual abuse.

As Frontier reported at the time, MacGregor’s departure from the Myanmar Times was preceded by a phone call to the paper’s management by the Ministry of Information – bypassing the Myanmar News Media Council, which was established to adjudicate press complaints. Speaking to a senior editor shortly after Frontier’s report was published, Aung Saw Min denied her termination had been prompted by the ministry’s intervention, and said the paper’s management had made the decision of its own accord.

The day MacGregor was sacked, staff were ordered not to publish any news reports on events in Rakhine State until a new editorial policy was drafted in the following days. Days soon became weeks, in which repeated written requests to Tegjeu and Aung Saw Min for the new guidelines were ignored.

By this stage Tegjeu was in the office no more than a few hours a week, and refused meetings with staff. Editors were livid: Not only were they being prevented from reporting on the biggest news story in the country, Tegjeu had refused to shoulder any responsibility for MacGregor’s report, despite his repeated interventions to dictate the limits of the paper’s coverage.

The ructions in the paper’s office quickly became the worst-kept secret in Yangon. Foreigners at the paper made no secret of the fact that they had been censored, with some sharing the news with friends and professional contacts, and others providing a running commentary on social media on what they regarded as a professional embarrassment.

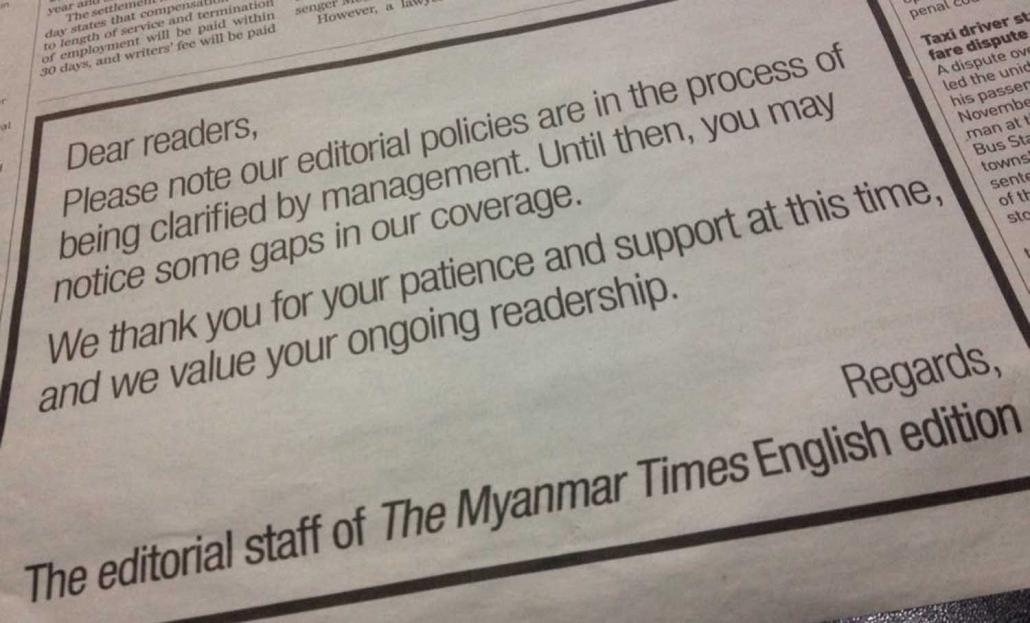

As the ban became more obvious to readers, editorial staff began to feel that the paper’s credibility was at stake: They caucused and decided to print a notice that alluded to the prohibition on coverage of the Maungdaw crackdown.

“We thank you for your support at this time, and we value your ongoing readership,” it read.

The notice that ran in the Myanmar Times, after management banned news coverage on the ongoing crackdown in northern Rakhine State.

The notice ran for a few days. Then Aung Saw Min sacked Mr Douglas Long, who had been on staff for more than a decade and was by that time editor of the English edition.

“I was given notice of my termination via email,” Long told Frontier the following day. “The letter stated in part: ‘The board and the management are of the view that as editor of the paper you deliberately undermined the interests and reputation of the company by allowing the notice to the readers to be run in the [Myanmar Times English] issue of November 8, 2016, commenting on the MCM’s editorial policies.’”

Asked how he felt about the continuing restrictions on Rakhine coverage, Long did not mince words.

“Well, it sucks. In two short weeks, management has managed to destroy the trust that editors and reporters have spent years building with our readers.”

By the time of Long’s dismissal, 13 foreign staff members had quit or been sacked from the Myanmar Times in the preceding six months. Only three people were hired to fill the vacant positions. More were to leave soon.

‘I’m not in bed with anyone’

The communal violence that twice rocked Rakhine State in 2012 claimed about 200 lives and forced about 140,000 people, mainly Rohingya, into squalid displacement camps, where most remain today. In the years since, editors have faced regular pressure from authorities to demur from covering the grave human rights situation in Rakhine in a manner which strays too far from the official line.

typeof=

The Myanmar Times has been no exception. In March 2014, reports of a massacre in the Maungdaw village of Duu Chee Yar Tan provoked a strident response from the Thein Sein administration, after a government investigation could not find evidence to substantiate the claims. State media named outlets it accused of spreading false coverage, which were then inundated with complaints and threats.

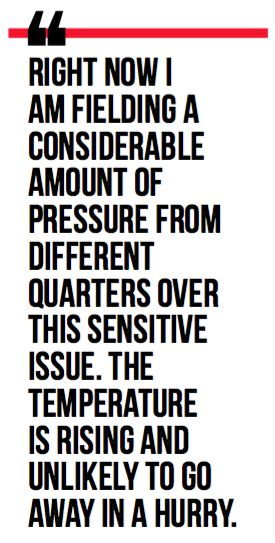

It was in this climate that the paper’s co-founder – the brash and controversial yet dynamic and driven Australian publisher Dunkley – issued a notice forbidding the publication of any reports about the Rohingya or communal tensions without his approval.

“Right now I am fielding a considerable amount of pressure from different quarters over this sensitive issue. The temperature is rising and unlikely to go away in a hurry,” he wrote in the memo, leaked to Washington-based Foreign Policy magazine. “I am surrounded by a number of forces from the president’s office downwards and from my own directors and editorial consultants. … There are plenty of people out there that would like to see us go down or be pegged back.”

Unlike last year’s management edict, the memo did not impose an outright ban on covering events in Rakhine. The memo was also a product of a wisdom that Tegjeu lacked: More than any other foreigner who has worked in Myanmar’s media industry, Dunkley had come to learn the limits of acceptable public discourse.

After helping to establish a business journal in the early 1990s in Vietnam, a country then in thrall to the sudden changes of its own economic liberalisation, Dunkley established the Myanmar Times in 2000 in a partnership with Sonny Swe, the son of then senior Military Intelligence officer, Brigadier-General Thein Swe. (Sonny Swe is the chief executive and publisher of Frontier. Both he and his father are board members of Black Knight Media Co Ltd, the owner of Frontier. Neither was involved in the commissioning or production of this article.)

Dunkley and Sonny Swe launched the Myanmar Times in the political and economic nadir of the junta years. Their motives were suspect to many at a time when international opprobrium was forcing Western companies to leave Myanmar. In Thailand and in India, where many student activists had fled after the 1988 revolt against one-party rule, some exile media outlets were established to report on the human rights situation in Myanmar, as the junta that took power in September that year tightened its group on the country. The Irrawaddy, founded in the early 1990s with the help of US funding, regularly reported on the Myanmar Times’ many foibles in the paper’s formative years. One article gave a breathless account of a slanging match between Irrawaddy founding editor U Aung Zaw and Dunkley in 2002, during a panel discussion at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand in Bangkok, in front of an audience palpably hostile to the Australian.

Accusations of collusion with the junta were always shrugged off by Dunkley with an air of nonchalance. Publicly, he always maintained that there could be no change in Myanmar without engagement with those in power. In Dancing with Dictators, a 2011 documentary about the Myanmar Times made by two Australians who spent weeks at the newspaper before and after the 2010 general election until they were deported, Dunkley is asked what he says to those who accuse him of “getting into bed” with the military.

“Well the fact is, I’m not in bed with anyone. Not even my wife,” he says with a wry laugh. “If you want to instigate change, then you have to be on the field. Anyone who’s screaming from the sidelines, it’s just a shriek that’s going off into the wilderness.”

The paper’s existence seemed doomed on several occasions, as the factional balance of Myanmar’s leadership tipped decisively back to the head of the junta, Senior General Than Shwe.

In 2004, a year after he was appointed Prime Minister, Military Intelligence chief Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt was relieved of his post and dismissed from the junta.

It was Khin Nyunt who had approved the establishment of the Myanmar Times, the only news organisation at the time with any foreign investment. He also allowed it to pass the usual censorship regime administered by the Ministry of Information’s Press Scrutiny and Registration Division and to be censored by an office within MI.

Khin Nyunt’s sacking, amid heightened tensions between him and Than Shwe, led to a sweeping purge of Military Intelligence and those associated with it. Scores of senior MI officers were detained in the weeks after Khin Nyunt was arrested in October 2004 by General Myint Swe, the then head of the Yangon Regional Military Command and now the military’s pick as vice president. Thein Swe was subsequently sentenced to more than 140 years in prison, including convictions for several counts of treason; Sonny Swe was sentenced to a total of 14 years in prison: seven years each for having failed to submit the English and Myanmar editions of Myanmar Times to PSRD to be censored.

Against Dunkley’s protests, a controlling stake in the Myanmar Times was transferred to Dr Tin Tun Oo, a close associate of hardline Information Minister and Brigadier-General Kyaw Hsan. Tin Tun Oo had established himself as a media entrepreneur by publishing a suite of lifestyle journals. It was an unhappy partnership.

In 2010, and despite Dunkley’s objections, Tin Tun Oo stood as the Union Solidarity and Development Party’s candidate for the Pyithu Hluttaw seat of Pazundaung Township, a downtown Yangon constituency near where Myanmar Times is based. He was one of the few USDP candidates who failed to be elected in the notoriously rigged election. “It is unacceptable to steal an election, as the regime in Burma has done again for all the world to see,” said then US President Barack Obama.

The following year, Dunkley was arrested and held in Insein Prison over allegations involving a woman he met in a Yangon nightclub and invited to his Inya Road home. The case was strongly believed by many of Dunkley’s colleagues and friends to be an orchestrated attempt to force him to yield control of the Myanmar Times. It coincided with a demand from the ministry for him to relinquish his positions as CEO and editor-in-chief of the company. His refusal had resulted in foreign staff at the paper having trouble renewing their visas.

Myanmar Times cofounder Ross Dunkley leaves Kamaryut Township court after his final appearance in June 2011, following his 44-day detention in Insein Jail. (Soe Than Win | AFP)

Dunkley spent 47 days in Insein before being released on bail and was subsequently convicted of assault and breaching the conditions of his visa. The relationship between Dunkley and Tin Tun Oo continued to deteriorate. In 2013, Tin Tun Oo’s wife threatened legal action, which never came to fruition, after Dunkley allegedly struck her son-in-law during a heated argument in the office. The incident occurred after Dunkley had reminded Tin Tun Oo and his wife of their agreement not to enter the office except to attend board meetings.

The month before the 2014 Rohingya memo, Tin Tun Oo had sold his majority stake to U Thein Tun, a beverage magnate and head of the Tun Foundation Bank, popularly known for being the businessman who brought Pepsi to Myanmar. He inherited a paper that had never run at a loss, according to Dunkley, who sold his remaining interest in Myanmar Consolidated Media in early 2015.

His exit from the chief executive role in October 2014 was announced publicly through a Myanmar Times article, accompanied by a photo of Dunkley with Child, his ill-fated replacement. As an era came to an end, Thein Tun was quoted promising major investments to grow MCM’s existing businesses and branch out into new ventures.

“I’m confident that with such a talented group of staff – really the company’s greatest asset – that we can move MCM forward in the coming years,” Thein Tun said.

‘National interests come first’

With no end in sight to management’s censorship policy, it was with Thein Tun that the remaining senior members of the editorial team sought an audience in November 2016. The number of editors producing the paper was down to half what it had been in April. In an environment of unrelenting stress and collapsing office morale, they desperately wanted assurance that a new editorial policy was forthcoming, as well as a promise that the positions vacated in the preceding months would be filled.

A meeting was finally granted after a written request was delivered to Thein Tun’s office at his bank’s headquarters not far from the Myanmar Times office. Management was represented at the meeting by Thein Tun, Tegjeu, Aung Saw Min and Tan, who had travelled from Singapore. The three foreign editors at the meeting included one conscripted at the eleventh hour to replace Long, who had been sacked earlier that week.

The discussion did not go well, said one of the editors present. Presented with an organisation chart showing the number of editorial positions that had been vacated, Tan seemed to be shocked. Thein Tun, on the other hand, appeared disengaged and distracted throughout the meeting and the delegation was unsure if he had understood their position.

After the meeting ended, some staff members felt that at least partial progress had been made in rescuing the paper from its parlous state. They had been told an editorial policy would be provided immediately and editors who had left would be replaced. Others believed that the commitments made by the board did not go far enough.

Within days, Aung Saw Min circulated the new editorial policy. Its first two points declared that “national interests come first” and, echoing the platform of the Union government, the paper had a duty to “promote national reconciliation”. News on Rakhine had to be cleared with the editor-in-chief, while outside opinion pieces on the situation in Rakhine were prohibited until further notice.

Within three months, all three foreign editors at the meeting had left the newspaper. Seven other foreigners left with them.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

As 2016 ended, it became clear that there was no solution to the conflict with management. Tegjeu, never a permanent fixture in the office, was seen less often. More of the responsibility for scrutinising the paper’s contents fell to deputy editor-in-chief U Myo Lwin, another long-time staff member who had risen through the ranks and was a faithful lieutenant to Aung Saw Min.

Editorial staff members told Frontier their Myanmar counterparts had warned them in 2015 that Myo Lwin had used their weekly meetings to sow distrust of foreigners, telling reporters that the Westerners did not understand the country and would make trouble for the paper. An editorial supplements editor at the time, his colleagues did not pay attention to his comments; a year later, he was one of the most senior members of editorial management, and was assisting what editors by then regarded as a policy designed to drive the remaining foreigners out of the paper.

Tegjeu had begun deflecting requests to accelerate recruitment by saying that Aung Saw Min and Myo Lwin were drafting an organisational restructure – the editor-in-chief had initially been involved in these strategy meetings, but stopped being invited as his own position became more tenuous. Changes to the paper’s reports had meanwhile ceased to become a topic of discussion; in any event, there were few editors left to object. In January, an entire report of a briefing given by the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, Ms Yanghee Lee, on her visit to the country was cut at the last minute. On the same page, a report about the disappearance of two Kachin pastors, who were believed to have been detained by the military, was edited to remove quotes from their families saying they feared reprisals from the Tatmadaw.

‘I am above you’

On February 1, a year after Tegjeu joined the paper, Tan issued a memo to staff advising them of the editor-in-chief’s resignation for “family reasons”. The same day, Tan announced that veteran Thai journalist and academic, Mr Kavi Chongkittavorn, would be taking over from Tegjeu.

The priorities that prompted the Myanmar Times to shed nearly all of its expatriate staff remain unclear. Tegjeu has not responded to multiple requests for comment from Frontier since October. Kavi did not respond to a request for comment made soon after his appointment. Neither Thein Tun, Aung Saw Min nor Myo Lwin replied last week when asked to respond to the events outlined above.

What is clear is that events at the Myanmar Times during the last year have exposed deep and perhaps irreconcilable differences in how Western journalists and their Myanmar managers view their professional responsibilities. Occasionally surfacing while Dunkley still held a stake, these tensions are now in plain view.

On the one hand is a cohort from countries with a long history of press freedom, and long-established norms of ethical professional conduct. On the other, a country that until recently laboured under a stringent censorship regime for decades, with the accepted limits of what can be written incorporeal and constantly changing but nonetheless still very real. The jailing of a dozen journalists during the last government and the deaths of two since 2014 – one in military custody and the other apparently the victim of powerful business interests – attest to the risks Myanmar journalists face.

Staff at the Myanmar Times watched as the culture of their office changed to one that privileged deference and punished disagreement. Two former staffers who spoke with Frontier recalled Aung Saw Min prematurely ending arguments over the direction of the paper by telling them: “I am above you. You are below me.” It is a management model that journalists in several other Yangon newsrooms would well recognise.

Most fundamentally, it reveals a differing attitude to freedom of expression, between those who come from a culture where it is a paramount responsibility of journalists and those who believe it is contingent on protecting the common good.

Several of those who commented publicly on events at the Myanmar Times said they felt an ethical responsibility to explain what was happening at the paper if, as it appeared, the conflict between editors and management could not be resolved internally. To management, such an action was not only a breach of its professional guidelines, but a potentially criminal act.

One evening in February, in the days after Tegjeu’s resignation was announced, one of the few remaining editors was called into a meeting with Aung Saw Min and Myo Lwin. The editor was told that as a result of the organisational restructure, their position was being terminated. Myo Lwin referred to the comments on social media and said they could fall afoul of Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law, which punishes online defamation with up to three years’ imprisonment and has been used with increasing frequency to suppress criticism of the government and the military. (Asked by the editor, Myo Lwin denied issuing a threat, but reiterated that the editor should warn other former staffers to “be careful” in their public comments about the paper.)

Kavi is well respected as a journalist, analyst and educator. Former staff members and others believe he offers the best hope of turning around the paper’s flagging fortunes and bridging the divides outlined in this report.

It will be a momentous challenge. He has walked into a newsroom that has lost a significant amount of experienced editorial talent, to lead journalists concerned for their own futures, who have become accustomed to self-censoring controversial aspects of their reports for fear of losing their jobs.

“The staff don’t feel safe since they are being sacked without notice,” one Myanmar staff reporter told Frontier. “If the management goes on as it is now, Myanmar Times’ future is very worrisome. You’ll realize if you look at Myanmar Times policy on Rakhine State. You cannot criticise the government. … Some of us are looking for new jobs. Some are just waiting to see in the hope of better situation when new management comes in.”

Speaking to Frontier in February, Dunkley offered a sympathetic word for Thein Tun. Despite the upheaval of the last year, Dunkley said Thein Tun had come to the paper with a lifetime of success in business and would inevitably also find success at the Myanmar Times.

“What effectively happened to U Thein Tun was that in his rush to assert authority over the Myanmar Times he found himself increasingly bewildered over the actions of his newsroom and confused on how they should be managed,” Dunkley said.

“He became alienated from a team of people he didn’t understand anyway and suddenly and awkwardly caught in the cross fire as the government and military started to make their displeasure known over the recalcitrant behaviour from the press. … Today, he is still grappling with that scenario.”