Weak laws and the government’s failure to regulate jade mining companies contributed to the deaths of 54 miners after one of more than 20 tailings dams at Hpakant collapsed.

By CLARE HAMMOND and YE MON | FRONTIER

An elderly Kachin man wearing a white collared shirt and traditional checkered longyi stands alone, staring over the edge of a precipice. He is dwarfed by the ravaged landscape of Maw Wan Lay, a jade mining area north of Hpakant, in central Kachin State about 180 kilometres west of Myitkyina.

On the ground beside him is a shrine: red roses, white chrysanthemums and a photograph of his son, delicately arranged on top of a mound of stones.

Three photographs of the bereaved father’s tribute were uploaded to Facebook by his daughter, Ma Lu Lamung, on April 26.

“Who would have understood the agony of a father whose only son perished. Not even a dead body to grieve over,” she wrote in her post. “My father kept looking down in tears to see whether he would get a glimpse of the body.”

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Her brother was buried alive four days earlier while working the night shift at a jade mine operated by Shwe Nagar Koe Kaung Company.

Looming above him as he worked was an informal tailings dam in a disused mine formerly operated by Unity Gems Company. After Unity’s licence expired in October 2017, the open-cut site filled with water; after 18 months of illegal waste dumping by other miners, it was a lake of thick, unstable mud that covered at least three acres (1.2 hectares) and was 100 feet (30 metres) deep.

“It was like an infinity pool over the miners’ heads,” U Maw Htun Aung, Myanmar country manager for the Natural Resource Governance Institute, told Frontier at his office in Yangon. “At the same time the miners did not stop digging and using dynamite to blast the rock apart,” he said. “They were basically living under a time bomb.”

At about 11.30pm on April 22, the thin earthen wall that contained the dam collapsed, releasing a torrent of mud that surged into the open-cut mine below, submerging the workers.

The next day, the Ministry of Information announced that 28 employees of Myanmar Thura Gems Company and 26 miners who worked for Shwe Nagar Koe Kaung Gems (Nine Golden Dragons) Company had been buried under the mud, along with 40 pieces of machinery owned by the two companies.

What the report elided was that Myanmar Thura did not have a permit to mine in the blocks affected by the dam’s collapse. Nor did the other two companies that were reportedly extracting jade in the same area: Chaow Brothers Gemstone Enterprise, also known as Chaung Brothers, and KNDPC, or Kachin National Development and Progress Company.

A Frontier investigation has found that this tragic accident at Hpakant was preventable and the result of a lack of political will and long-standing policy failures that have, if anything, worsened under the National League for Democracy government.

The legal framework for jade mining is completely unsuitable for the nature of the business and has worsened under a newly introduced Gemstone Law. The companies were able to operate at the site without permits due to a lack of enforcement. The government has failed to ensure companies follow environmental and safety rules, and has stalled on planned reforms in these areas. The companies themselves were unwilling to acknowledge and act on the risks of mining so close to the dam.

Deadly landslides are common in Hpakant. They are typically caused by the partial collapse of designated tailings heaps, where itinerant miners known as yemase are permitted to forage for pieces of jade among the crushed rock discarded by mining companies.

The collapse of the tailings dams represents a new danger, though. Maw Htun Aung said at least 20 similar dams have formed in Hpakant at abandoned mines since the government imposed a moratorium on renewing jade permits in April 2016, pending a review of mining laws.

Some of these are dangerously close to villages, he said, and Hpakant residents have been warning the government of the dangers for some time.

“It makes me sick that it could have been easily prevented,” he said. “The government has the power to shut down operations under the Environmental Conservation Law if they really want to save the lives of the people. If they don’t, it is very likely to happen again.”

Profit sharing

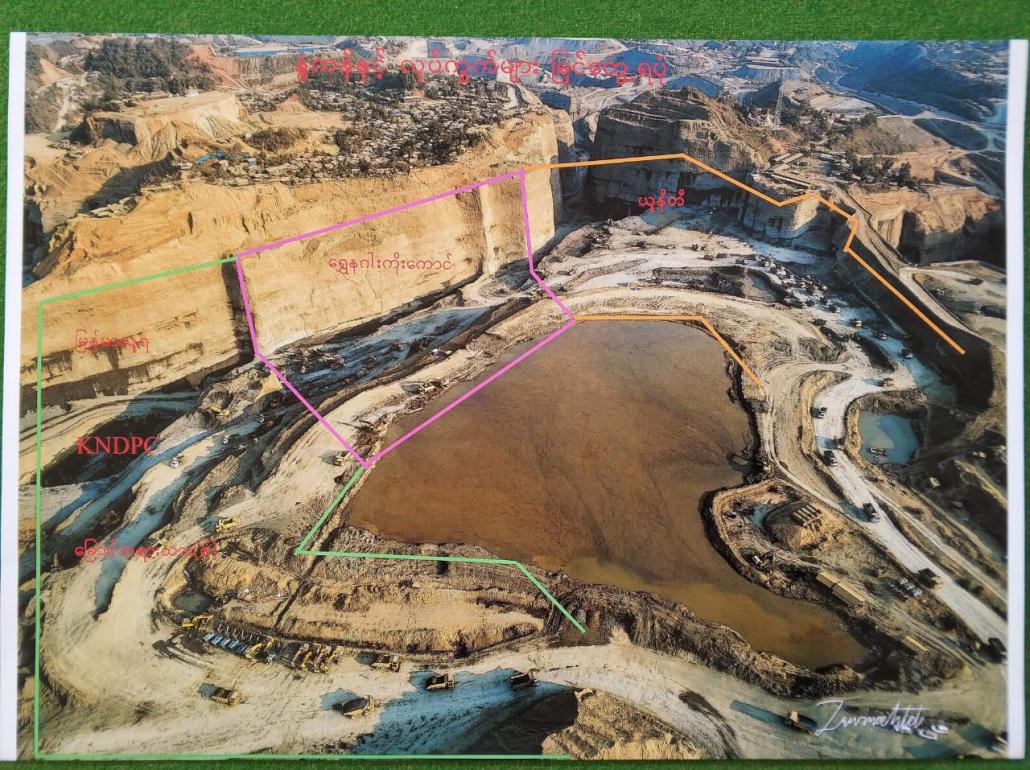

Two days after the tragedy, freelance photographer and journalist Ko Zaw Moe Htet posted two images to his Facebook page, showing the location of the collapsed dam and which companies had been operating in the area at the time of the accident, their mining blocks clearly demarcated.

These undated photographs appear to show where companies were mining without permits in the area of Maw Wan Lay before the April 22 landslide. (Zaw Moe Htet | Frontier)

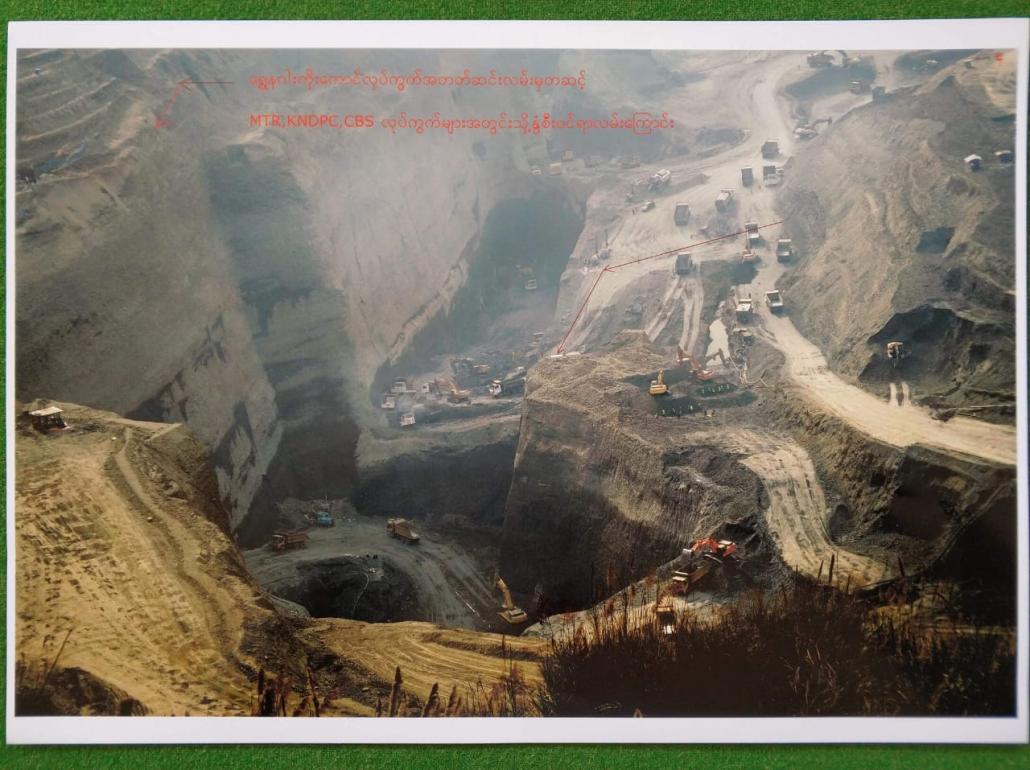

The passage (see red arrows) of the landslide into a mining pit, where it submerged at least 54 workers. (Zaw Moe Htet | Frontier)

Zaw Moe Htet manages the Hpa Kant News Facebook page. He contributes to the thin stream of public information about the jade mining region that reaches the outside world. Surveillance by security services and restrictions on civil society and media access to jade mining areas means that most of what happens in Hpakant is never reported. In the post, Zaw Moe Htet explained that many other areas in Hpakant are just as dangerous as Maw Wan Lay.

“One of the reasons for the accident is that the extension of mining licences has been stopped for a long time,” he wrote. As the number of active permits dwindles, companies with expired permits strike deals with those that have active permits to mine at their sites rather than seeing their businesses close. “Because there is no alternative, they are risking their lives and those of other people,” Zaw Moe Htet wrote. “Who is responsible?”

Frontier travelled to Nay Pyi Taw to put that question to U Thet Khine, deputy manager at Myanma Gems Enterprise’s Licence and Registry Department. MGE is a state-owned enterprise that operates under the Ministry for Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. It awards licences, oversees regulation, awards mining permits, acts as a joint venture partner for some mining companies and collects certain revenues.

Thet Khine confirmed that Myanmar Thura, KNDPC and Chaow Brothers did not have permits to mine the blocks affected by the dam’s collapse, and were not allowed to be mining at the site through any kind of sublease or profit-sharing agreement.

Four companies had permits to mine seven blocks in the immediate vicinity of the accident, he said: Pan Myat Noe Yoon Gems & Jewellery Company, Jade Akari Gems & Jewellery Company, Kan Seinn Pwint Jewellery Company and Malikha Gemstone Company.

Documents obtained by Frontier that appear to be from the MGE office in Hpakant indicate that Shwe Nagar Koe Kaung also had a permit to mine in the affected blocks.

Asked why companies were mining without permits, Thet Khine said it was possible that the companies with permits hired heavy machinery, such as backhoes, from those without permits. “So if someone asks the workers and operators of backhoes in the area, they would say, ‘We are from Myanmar Thura Gems, or KNDPC, or Chaung Brothers.’ Then there would be a misunderstanding that these companies were mining without a permit,” he said.

The sublease or transfer “in any way” of permits is illegal under section 16(e) of the 1995 Gemstone Law, under which the permits were granted. Thet Khine said that because the law does not refer directly to the transfer of machinery, it’s “hard to say” if the practice is legal or illegal. “It’s pretty complicated,” he said. “We are not able to control this situation.”

He said that MGE was working to include clauses in the by-laws to the new Gemstone Law that would grant it greater control.

But Mr Paul Donowitz, campaign leader for Myanmar at international NGO Global Witness, said it was more likely that the companies had entered into profit-sharing agreements. In 2015, the international NGO published an exposé that valued the underground trade in jade – known to its Chinese buyers as “the stone of heaven” – at US$31 billion.

“It’s common knowledge within the industry and within the most senior levels of MGE that some companies whose permits have expired enter into profit sharing agreements with companies who have active permits, to mine their plots,” Donowitz said in May. “In fact in response to our questions earlier this month on these arrangements, U Aung Nyunt Thein, managing director of MGE, told Global Witness, ‘Who will know? You may never know.’”

Rescue volunteers search for survivors on April 24, two days after the collapse of a tailings dam in Hpakant buried alive 54 miners. (AFP)

Mega-mines

In 2016 MGE commissioned Coffey Myanmar and Valentis Services to compile an Environmental Management Plan for the Hpakant and Lone Khin gems tracts. Although the EMP has been completed, the government is yet to sign off on it. Valentis declined to comment, including on the reason for the apparent delay in implementation.

A related advisory paper by the consultants in 2017 found that the legal framework makes it difficult for companies to comply with environmental laws. The small size of concessions – which has been limited further to three acres by the new Gemstone Law passed earlier this year – means that companies cannot mine at the depth necessary to extract much of the remaining jade.

The lack of space also means they cannot dispose of waste within their designated concession area. Instead, the government has established 12 designated waste disposal sites on the periphery of Hpakant. Freed from the need to dispose of tailings at their own sites, mining companies are combining the small blocks into what Maw Htun Aung called “mega-mines” to enable them to excavate to greater depths.

He said that to avoid making inconvenient and expensive trips to designated waste disposal sites, companies have been dumping their tailings at abandoned sites near their worksites, such as the former Unity mine that collapsed on April 22.

A related problem with the legal framework that Coffey and Valentis highlighted is the short duration of permits, which last for a maximum of five years. This is too brief to allow for the full mine lifecycle, including closure and final rehabilitation, the paper said. When their permits expire, mining companies are under no obligation to ensure the site is safe, let alone rehabilitate it.

This means that when mining permits expired and were not renewed, companies including Unity were unlikely to have reinstated stable landforms before abandoning their plots, which have now become tailings dams that are endangering the lives of thousands of miners.

Union and state-level government officials fail to understand the risks because their visits to Hpakant are arranged by mining companies, said Daw Kai Ra, president of the women’s department of the Kachin National Social Development Foundation in Hpakant. She said they do not meet civil society organisations or even residents.

The refusal to listen to local voices or empower CSOs meant that the government was failing in its duty to protect mine workers, she told Frontier.

Kai Ra said CSOs could play a role in monitoring the safety of mining sites, but without government support they were unable to conduct checks or collect data on companies.

But former Kachin State natural resources minister U H La Awng, who was forced to resign from his position in January, denied that the state government had failed to cooperate with CSOs.

“Local MPs and CSOs told me about the issue of unlicensed companies and I told them to give me solid evidence,” he said. “I asked them to tell me the companies’ names, but they couldn’t, because they have no evidence.”

For CSOs, obtaining evidence of wrongdoing is challenging because of a lack of public information. The EITI reports list permit holders and block numbers but there is no corresponding public map showing their location.

Members of civil society were also worried about being threatened, Kai Ra said. “If we told you about unlicensed companies, our safety would be compromised, because the companies use the military and militias for protection.”

In 2015, Global Witness published an exposé that valued the trade in jade at US$31 billion. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

Armed groups

While some companies enjoy the protection of armed groups, others are actually owned by the armed groups themselves. When Frontier visited the registered address of KNDPC, one of the companies that was believed to be operating at the site of the tailings dam collapse, a woman who was living there said that it was the address of the Kachin Defense Army.

The KDA, also known as the Kaung Kha militia, is a Tatmadaw-aligned force that split from the Kachin Independence Army’s Brigade 4 in 1991. Its leader, U Ma Htu Naw, is a shareholder in KNDPC. The woman said Ma Htu Naw was at Kaung Kha, the militia’s headquarters in Shan State, and gave a number for a phone that was switched off.

At least two of the companies with permits to mine in the blocks affected by the tailings dam collapse are also linked to armed groups. Shareholders of Malikha Gemstone Company include U Ray Dam Taung, the leader of the Tatmadaw-aligned Rawang People’s Militia Force based in Putao, northern Kachin State.

Pan Myat Noe Yoon Gems & Jewellery is registered to the same address as a company whose shareholders include Sai Philip Yee, who was identified by Global Witness as a direct representative of Wei Hsueh Kang, a financier of the United Wa State Army. Neither of these companies responded to our requests for comment by press time.

Pyithu Hluttaw MP U Tint Soe (National League for Democracy, Hpakant) told Frontier that members of the Kachin Independence Army, the armed wing of the Kachin Independence Organization, were also mining illegally in the area. KIO spokesperson Colonel Naw Bu said he had also heard that KIA members were mining illegally in expired plots. “I’m not sure whether it is true,” he told Frontier, adding that the group had a policy against illegal mining. “The KIO is now investigating,” he said.

Donowitz at Global Witness said the armed groups active in the jade industry are involved in and benefit from corruption, extortion, illegal mining and informal taxation, all of which fuel the conflict. “These conflict actors have little incentive to change the status quo which could put at risk the massive illicit revenues which line their pockets, but should benefit the people of Kachin and Myanmar,” he said.

Frontier was unable to contact any of the other companies that were reportedly mining at the time of the tragedy. They do not have websites or Facebook pages, and numbers provided by sources in Hpakant were for phones that were switched off.

The addresses registered for Chaow Brothers and Myanmar Thura with the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration were home to a family and a young couple, who said they had never heard of the companies.

Shwe Nagar Koe Kaung is registered to the address of a popular restaurant in Mayangone Township called Jeff’s Kitchen. The confused receptionist said the restaurant’s owners had been renting the building for six months from a family that lived next door. She pointed towards the neighbouring house, half-concealed behind high walls fortified with barbed wire. There, a young woman dressed in pyjamas told us that we had the wrong address.

The registered addresses in Yangon of companies that mine jade in Hpakant, seen in May. Few actually function as offices. (Steve Tickner and Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Life and death

The government suspended jade mining permits in 2016 with the objective of reforming the industry. Since then, it has taken steps to improve the legal framework and ensure a safer working environment for yemase, the itinerant miners. A new Gemstone Law was passed earlier this year and the by-laws have been submitted to the Attorney General’s Office for review.

The EMP compiled by Coffey and Valentis is ready to be adopted by mining companies and is awaiting final sign-off from the government. Thet Khine of MGE said it was only likely to be implemented in full when all of the 1,009 remaining licences awarded under the 1995 Myanmar Gemstone Law had expired in 2021.

But Maw Htun Aung said that what has been happening at Hpakant is “unacceptable” and that the government should take action immediately. “These matters are life and death. If the government gives out licences, they should have enough technical, human and financial resources to do their job [as regulator] properly and parliament should monitor them,” he said. “There is no reasonable ground for the government to allow companies to keep on mining unless they have the framework of safety in place.”

After the April 22 tragedy, MONREC ordered a suspension of mining activity in 17 blocks operated by 11 companies that it deemed unsafe because of their proximity to the collapsed dam. The new Kachin State minister for natural resources U Dar Shi La Sai told Frontier that his ministry is still investigating what caused the dam to collapse.

“We can take action against the responsible persons when we get the exact information,” the minister said. He added that the government sometimes overlooked violations by the companies, claiming that it did so in the public interest because so many people depend on the mines for work. “If we shut down the companies, the companies won’t mind but the workers will be jobless,” he said.

Maw Htun Aung said that although all of the companies involved in the tragedy appeared to have broken the law they were unlikely to be punished. “The companies knew there was a risk but did nothing to make their workers safe. In a well-developed country you would open a case of criminal negligence. But here nobody ever thinks that way,” he said.

Instead companies have settled the matter in the traditional way. They gave about K30 million (US$19,500) in compensation for each person who died, he said. This would ensure that the families of the victims would not file a complaint to the authorities against them.

The families had to sign agreements saying they accepted the compensation, said U Myint Aung, whose son Ko Bo Tine, 19, and son-in-law Ko Min Min Zaw, 26, were both killed on April 22. The young men left their hometown of Chauk in Magway Region for Hpakant and found work in 2017 directing dump trucks for Myanmar Thura.

“The compensation amount is small for the company; a single jade stone is worth more. How can we be pleased with it?” Myint Aung told Frontier. “If I had a chance to buy my son with this amount, I would buy him and bring him back home. He was too young to die. We want him to come back home.” – Additional reporting by Kyaw Ye Lynn