Yangon’s once-prominent Armenian community has dwindled over the decades, but its sense of history, heritage and identity remains strong.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

YOU COULD count the congregation at the Armenian Church of St John the Baptist, Yangon’s oldest place of Christian worship, on one hand.

There was a young expatriate in the third pew, his head bowed in prayer, a little girl squirming in the front row, and her mother, wearing a lace veil and holding a hymnal. A choir of one, her clear, rich voice rose through the old beams and dusty portraits of Christ and the saints as the priest and lay vicar delivered the liturgy and homily and served Holy Communion.

Later, waiting for a torrential downpour to ease, the entire assembly sat with me under an awning at the 150-year-old building on downtown’s Bo Aung Kyaw Street. I had come at an odd time, they explained. The service had been held on a Saturday because the Armenian Church in Kolkata, India, which sends one of its priests to Yangon every second week, could not spare anyone for that Sunday.

“Normally we have a few more,” said Ms Rachel Minas, the woman with the lovely singing voice. “But never more than ten, except maybe on special days like Easter.”

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Rachel and her father Richard, who had assisted the priest, were born and raised in Myanmar; the expat was Russian and the priest was born in the Republic of Armenia, a small former Soviet state.

Although the congregation of five hailed from three different countries, it shared an identity forged over centuries, one that continues to bind Yangon’s tiny community of Myanmar-Armenians, even if they don’t all show up for church services.

“We are like family,” said the priest, Father Artsrun Mikayelyan. “I know he is Armenian. She is Armenian. I am also Armenian …Wherever you go in the world, you will always find at least one Armenian.”

Once a prominent community of merchants and diplomats, the number of Armenians in Myanmar has dwindled to a few hundred at most. Yet they continue to learn Armenian (if only for liturgy and hymns), uphold Armenian traditions (even if they celebrate Thingyan alongside Orthodox Christmas) and maintain their church (even if many have become Buddhists).

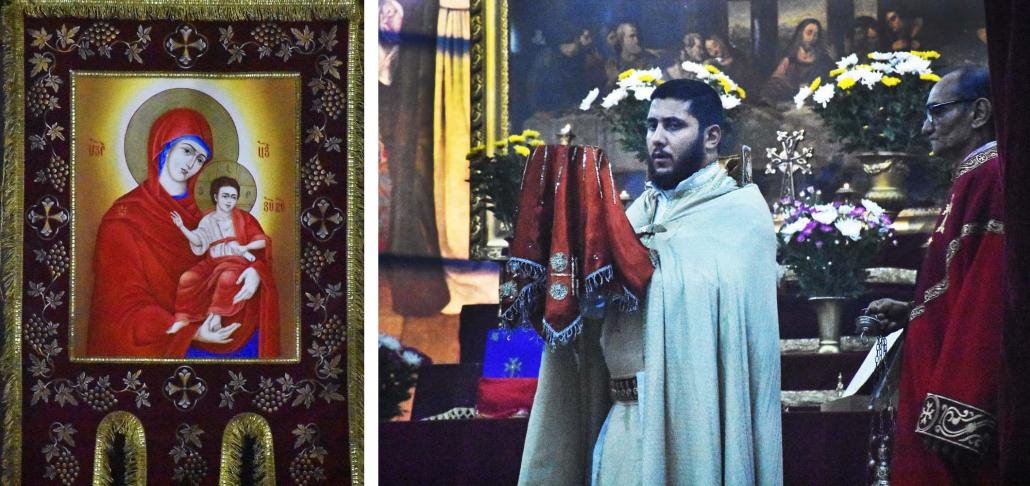

Father Artsrun Mikayelyan administers a service at St John the Baptist Church on June 29. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The Armenian diaspora is in many places linked to the mass exodus that followed the Armenian Genocide at the end of World War I. However, the Armenian presence in Myanmar dates to the 17th century, when Armenians from a population that had settled in what is now central Iran sailed to Southeast Asia to trade in silk.

Industrious, diplomatic and possessing a famous aptitude for languages, Armenians served as advisors in the royal court at Ava and later Mandalay. They were later translators and clerks for the British colonial government and high profile trading partners with the East India Company. At its peak, the community numbered at least 1,300 people living in India, Burma and Indonesia, shows census data collected by the BBC.

Rachel is well aware of the community’s rich history. As a schoolgirl she never failed to point out to her friends such icons of Armenian business acumen as the Strand Hotel, once owned by famous Armenian hoteliers the Sarkies brothers, and Balthazar’s Building on Bank Street, built in 1905 by the Armenian company Balthazar & Son. Her friends usually responded with blank stares.

“At school, people were confused because our faith was different and they didn’t know where Armenia was,” Rachel said. “It was a bit hard growing up here because most of the Burmese people considered us as foreigners, sometimes mistaking us as Indian or Muslim.”

Rachel doesn’t think of herself as a foreigner, but although she speaks Burmese and looks Myanmar, she doesn’t think of herself as a fully Myanmar person, either. She and her family exist in an obscure niche in the social landscape, one occupied by the community’s tiny church, a handful of other families, and the knowledge of an Armenian diaspora beyond Myanmar’s borders, scattered but strong.

Rachel’s distant cousin, Ms Sharman Minus, was born and raised in Canada, but her father grew up in colonial Rangoon. When his health began to decline, Sharman started researching some of the stories from his boyhood in Burma, and she soon found herself down a historical rabbit hole that would lead to previously unknown ancestors.

“It was a shocker to learn I was part Burmese,” she said.

The Armenian Church of St John the Baptist in central Yangon. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Sharman was especially fascinated by Makertich J. Mines (his surname is a variant of “Minus”), who served as a customs collector in Pegu, now Bago, during the reign of King Mindon from 1853 to 1878. Fluent in both common and royal Burmese, he became Mindon’s kalawun, a sort of minister for foreigners.

When she first saw a photograph of Makertich, Sharman instantly noticed a resemblance. “I can remember looking at it and thinking, ‘That’s my dad.’”

When she finally visited Yangon in 2014, Sharman scoured the city, wandering through gardens and canvassing crumbling teak houses to discover where her great grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins may have lived. She also saw the ruins of the 18th century “Portuguese” church in Thanlyin, which is believed to have been founded by an Armenian priest named Nicolai de Agualar.

When she visited the Church of St John the Baptist in the downtown area, she discovered that one of the last refuges of the Armenian community was in dire straits. The church had fallen into disrepair and, worse, an unordained parishioner of Indian heritage, “Father” John Felix, was posing as its priest.

In the absence of an ordained priest, the man had slowly gained authority over services and the church property. Rachel and other parishioners were concerned he might try to acquire ownership of the land and the church, an accusation he vehemently denied.

Sharman joined Rachel and other Armenians in a campaign that saw the acting priest removed, control regained over the property and relations revived with the broader Armenian church. In October 2014, their efforts culminated in a visit by His Holiness Karekin II, Supreme Patriarch of the Armenian Apostolic Church and Catholicos of All Armenians.

Speaking to the largest congregation St John’s had seen in decades, and a small throng of reporters and photographers, His Holiness reaffirmed the commitment of the Armenian Apostolic Church, saying: “We have come here to encourage Armenians and their children to preserve the tradition. We have come here not only to see the preservation of the church, but also to strengthen [Yangon’s] Armenian heritage,” The Irrawaddy reported at the time.

The following month, Sharman would write in her blog, Chasing Chinthes: “The church has already had two baptisms, a sure sign of regeneration.”

Father Artsrun Mikayelyan (top) and a view of the altar at the Armenian Church of St John the Baptist. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The regeneration has been gradual. The property dispute with the former would-be priest continues and has delayed renovation work, said Rachel, and church services rarely see more than a handful of attendees.

But despite the small congregation, the church continues to serve as a bastion of heritage and as a meeting place for all Yangon’s Armenians, regardless of whether they were born in Myanmar or abroad, such as Mr Vadim Zakharyan, the young expat at the Saturday service, and regardless of whether they are even Christian.

“When I first came here, I stayed in this hotel nearby. I was just walking down this street and I see this tablet that said, ‘Armenian Church in Yangon.’ I was shocked,” Vadim said.

He said it was comforting to know there were Armenians in Yangon. He was born in Uzbekistan and raised in Russia, and yet, like Rachel, has always thought of himself as Armenian more than anything else. Even though they did not speak the same language, he felt a close bond with the Armenians of Myanmar.

“Growing up, even though people did not know where Armenia was, and didn’t know what I was, I was proud,” said Rachel.

For her, the true value of the Armenian community is not measured in the size of its church, or city landmarks built by Armenians, or the number of remaining Armenian families. It is the invisible bond that links Armenians wherever they are, be it Yangon, Russia, Canada or the homeland itself.