Discarded fishing gear brings death and destruction to marine environments and is threatening the unique beauty and biodiversity of Myanmar’s Myeik Archipelago.

By THANDA KO GYI | FRONTIER

MYANMAR has a massive ghost net problem. Reefs are being smothered and marine life is being killed. There is no witness to the devastation and few are talking about it.

Ghost nets or ghost gear, also known as ALDFG (abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear), are fishing nets, lines, pots or other traps left in the ocean accidentally or deliberately. Ghost nets are becoming a huge global problem, both ecologically and economically.

Over the past 50 years, global demand for seafood has more than doubled. This increase has resulted in more fishing boats, which in turn has given rise to tons of ghost nets littering marine habitats, killing marine life and contributing to the plastics crisis.

There are various causes for ghost gear. Nets get lost because of bad weather and drift until they get stuck on pinnacles, rocks or reefs. Nets are abandoned when they get snagged on rocks or coral when fishing too close to reefs. Sometimes, nets are discarded when they break and there is neither a disposal faciliity nor room on the boat to bring them back to shore.

Whatever the reason, ghost gear silently continues catching and killing marine life for years, contributing to the depletion of our once abundant ocean and destroying ecosystems that are a source of food and income.

A United Nations study published in 2009 estimated that 640,000 tonnes of ghost gear was littering the world’s oceans; the amount has probably swelled substantially since then, given the growth of the global industrialised fishing industry. A survey by Netherlands-based NGO The Ocean Cleanup that concluded in 2016 found that 46 percent of the plastic in what’s known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is derelict fishing gear.

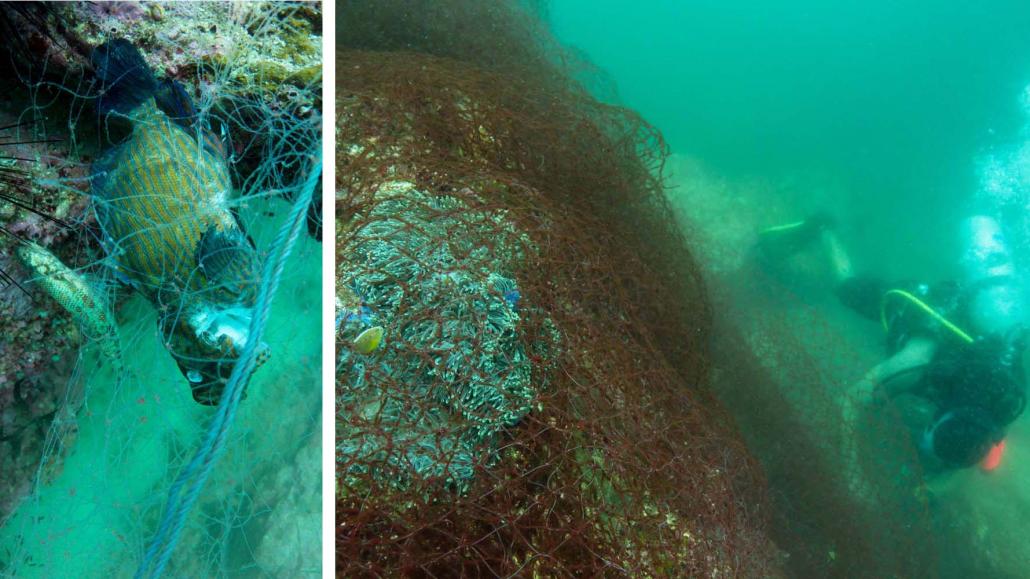

Marine life in the Myeik Archipelago smothered with discarded fishing nets. (Thanda Ko Gyi | Myanmar Ocean Project)

Most fishing nets today are made of plastic. They weigh less, are more durable, and don’t biodegrade for up to 600 years. When they finally break down, they become microplastics that find their way into the food chain and onto our plate. We’re only just starting to understand how microplastics harm marine life and its consumers.

Whenever I go diving in Myanmar, I encounter all kinds of fishing gear. At first, I was angry. Then frustrated. Then I felt helpless. At some point, as much as I hate to admit it, I became used to it, just as I’ve got used to seeing fields in the Myanmar countryside littered with plastic rubbish and experiencing the breeze carrying the slight taint of burning plastic. I stopped being shocked when I encountered ghost nets while diving.

That was until I saw about a dozen bamboo sharks and some other reef fish entangled in a huge ghost net in the Myeik Archipelago, a string of about 800 islands in southern Myanmar’s Tanintharyi Region that was formerly called the Mergui Archipelago. Bamboo sharks live under rocks and only come out to hunt. Their home was covered by an enormous net and the little sharks stuck inside were probably all of the local population.

Had we visited this dive site a week later, we would not have found the sharks in the net. We would have seen just another net covering just another pinnacle. We would not have spent the dive trying to free all the animals before they died. Witnessing all this had a heavy impact on me.

About eight months later, I returned to the same dive site. I found the net exactly where we left it. There were no more bamboo sharks and significantly fewer reef fish. I realised that if ghost nets were not removed, the same grim scenario would be replicated across the archiplelago.

Last year, support for this larger project by the Global Ghost Gear Initiative, Ocean Conservancy and National Geographic Society, enabled me to found Myanmar Ocean Project with the goal of understanding the extent of the ghost net problem in Myanmar’s waters.

When I was planning our expeditions, I had some doubts. I wasn’t sure how to define a “successful” expedition. What if I didn’t find any nets? I would have wasted time, effort and funds. Maybe I’d just had bad dives and the nets aren’t everywhere.

Divers retrieve ghost nets in the Myeik Archipelago. (Thanda Ko Gyi | Myanmar Ocean Project)

We spent seven weeks in the Myeik Archipelago, surveyed 22 sites and retrieved more than 1,000 kilograms of nets. We completed the first expedition “successfully”, collecting data to understand the scope of the ghost net problem off Myanmar and conducting clean-ups.

However, there were many times during the expedition when I felt overwhelmed. I was overwhelmed by the sheer number of nets we found. Overwhelmed by the number of species caught or injured by nets, ranging from manta rays (Manta birostris) to reef and pelagic fish and crustaceans. I was also overwhelmed by the fact that despite the ghost nets, we encountered stunning and abundant marine life wherever we went. Myanmar’s bustling coral reefs and colourful pinnacles easily compete with the world’s top dive destinations.

But Myanmar’s dive industry is still in its infancy. All of this beauty could be gone in a few years before Myanmar people have a chance to appreciate what’s in their backyard and show it off to the world. The country might just be left with “dead zones” that deprive coastal communities of their livelihoods and hurt the fishing industry.

It’s not enough to merely survey and clean up. We found so many nets that, with our limited time and manpower, we had to decide which to retrieve and which to leave behind.

We need to find local solutions that make it easier for fishing boats to dispose of nets. We need more protected marine parks. We need to encourage sustainable fishing practices and the proper enforcement of bans on harmful methods, such as fishing too close to islands or using narrow-gauge nets. We need alternative incomes for fishers and their families. And as consumers, we should be more mindful of the consequences of our appetite, and avoid seafood brought to us via processing plants and industrialised fishing.

I’d like to see the sites we have cleaned stay clean, with no new nets being snagged. I’d like Myanmar’s marine life to preserve its health and abundance, and for the bamboo shark population at Sloop Rock, where all this began, to recover.