Fifteen years ago, dozens of military students from a newly established technology college were jailed after protesting against what they said were broken promises and disrespect from Tatmadaw officers.

By KYAW PHONE KYAW | FRONTIER

STUDENTS IN Myanmar have suffered for resisting oppression since colonial times and many paid a heavy price for struggling against dictatorship after General Ne Win seized power in a coup d’état in 1962.

Most student protests under military rule targeted the junta and its policies. But a little-known incident in 2002 was remarkable for involving military students.

It resulted in the dismissal of more than 3,000 students from a military engineering school and the institution’s permanent closure.

It’s little known for a number of reasons. The Tatmadaw tried hard to hush up the incident – not difficult in the days before censorship was lifted and Facebook had arrived. There is also a tendency of many activists to play down its significance in the annals of student protest precisely because it involved military students.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

One of the cashiered students, Ko Zay Yah Oo, 35, recently recalled the dramatic incident in an interview with Frontier but made clear he was speaking for himself and not on behalf on his 3,000 former classmates.

In 2000, Zay Yah Oo was among about 450 students in the second intake at the Military Technological College established by the Tatmadaw in Pyin Oo Lwin, home of the country’s elite officer school, the Defence Services Academy.

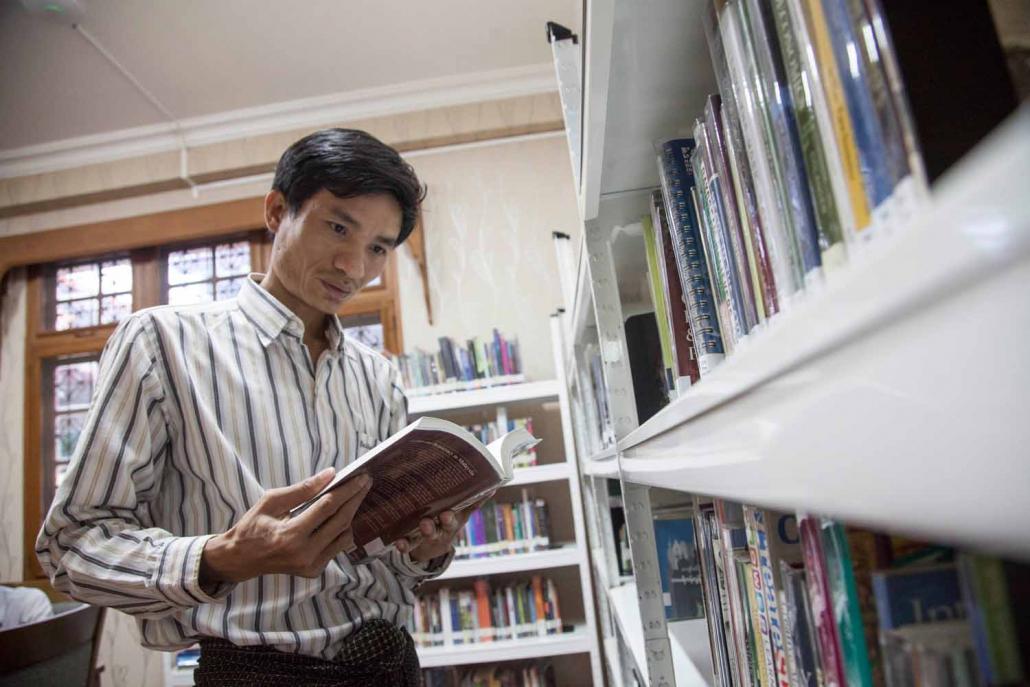

Former Military Technological College student Ko Zay Yah Oo, who received a five-year prison term for protesting against what he says were the broken promises of the military leadership. (Theint Mon Soe — J / Frontier)

The college had opened the previous year as the Tatmadaw Electrical and Engineering School (Pyin Oo Lwin), with a first batch of about 400 students. Its name was changed in 2000, and enrolments quickly grew, to more than 1,000 students in 2001 and more than 2,000 in 2002.

Zay Yah Oo, from Okkan in Yangon Region’s outer northern Taikkyi Township, had enrolled at the college because tertiary institutions under the Ministry of Education were closed at the time due to political instability.

“The problem did not emerge immediately; it was gradual,” he said, referring to the series of events that sparked the protest.

When the first batch of students enrolled in 1999 they were told they would study for two years for an Associateship of Government Technical Institute (AGTI) diploma.

If successful, they would be appointed as a “class b” professional sergeant and potentially be able to continue their engineering studies at a government technological college – one of the few pathways to a highly prized engineering degree given the military’s decision to close most civilian programs.

However, the first hint of the problems to come emerged in 2000, when the first batch completed their initial two years of study. Their parents were excluded from the convocation ceremony and only the leaders of the squads were invited onto the stage to take the diplomas, which were later distributed to students by the squad leaders. The students were upset at these perceived slights.

Then came the bombshell: only the top 100 academic performers were allowed to continue their studies, meaning the rest would enter the army as non-commissioned officers with the rank of sergeant. The students asked for an explanation but were never told the reasons for the change in policy.

The privileged 100 were also upset, though; they had been told they could undertake a Bachelor of Technology or Bachelor of Engineering at a civilian college, but instead were put into a new Bachelor of Technology program at the Military Technological College, for which the curriculum had not been properly prepared.

“All the students tried so hard because they wanted to join the army as professional engineers, not as a sergeant. I believe most of them qualified but were not allowed to advance to the next level, only the 100,” Zay Yah Oo told Frontier.

Zay Yah Oo’s batch had a similar experience and was not happy about it. An opportunity to demonstrate their irritation was looming.

Students at the MTC were summoned to the parade ground at the DSA to join officer students there in a rehearsal for their graduation ceremony. When they arrived for the rehearsal, they were disparaged by the DSA students, who regarded themselves as superior.

They were to graduate as commissioned officers with the rank of second lieutenant, while the MTC students would graduate only as sergeants. “You will become nothing. You will never qualify to be [commissioned] officers,” Zay Yah Oo recalled the DSA students saying.

“We didn’t have a single word to respond to them because our future was uncertain,” he said, referring to the doubt among the students whether they would be able to complete their studies for either a Bachelor of Engineering or a Bachelor of Technology and become the military engineers they had aspired to become when they enrolled at MTC. “We were murmuring to each other when we got back to our barracks.”

The MTC students resented being taunted by their DSA counterparts during the rehearsals and tensions rose. A rumour spread that in future none of the MTC students would be admitted to the bachelor degree program upon graduation. Eventually there was a nasty confrontation between the MTC and DSA students, during which bayonets were pointed. Luckily, the situation was defused and no one was injured.

The MTC students decided to take action to resolve the doubt over whether they could continue their studies and qualify as military engineers. In an audacious move, members of the first batch sent a letter to the three top leaders of the junta – Senior General Than Shwe, Vice Senior General Maung Aye and General Khin Nyunt – as well as the office of the Military Appointment General.

“He told us that our protest was the first such incident in the Tatmadaw and it must be the last and he would not allow our attitude to spread through the military.”

The letter asked why the military had broken its agreement and requested that they be able to continue their studies at the bachelor level and become professional officers. If they could not continue their studies under the terms of the agreement, the students asked to be discharged.

There was no response. “They submitted the letter again and again,” Zay Yah Oo said.

Junior students were dissatisfied with the tone of the letter sent by their seniors and sent their own letter. It made stronger demands but the result was the same – it was also ignored.

The students decided jointly to wait for a month; if they had received no reply they would desert and return home. They made secret plans to escape from the MTC college en masse.

It was about this time that some fourth batch students carelessly mentioned the secret plan in phone conversations with their parents. The parents were worried and did not keep their concerns to themselves. It was not long before Military Intelligence learned of the discontent at MTC.

A surprise raid was launched on the MTC barracks. Documents seized during the raid included a theoretical plan to incite protests among college students throughout the country.

Some student leaders were detained and locked up at the MTC. Others rioted and tried to raid the arsenal. Guards fired over their heads to try and bring the situation under control.

“The situation at the school was a mess. The students had rebelled,” Zay Yah Oo said.

MTC students from different batches held protest marches in their compound, blowing whistles and chanting their demands. Military Police were dispatched from Pyin Oo Lwin and deployed around the compound. The head of the MTC and the most senior Tatmadaw officer in Mandalay Region negotiated unsuccessfully with them to end their protest.

Finally, the chief of military training, Lieutenant-Colonel Kyaw Win, arrived to negotiate with the students, who were gathered on the parade ground. “We were surrounded by many soldiers pointing guns at us, but we were familiar with guns so we weren’t scared,” Zay Yah Oo said.

Several rounds of negotiations ended in failure. Eventually, Lt-Col Kyaw Win decided to allow the students to go home. He also shut down the school.

“He told us that our protest was the first such incident in the Tatmadaw and it must be the last and he would not allow our attitude to spread through the military,” Zay Yah Oo said.

Most of the students were permitted to go home, but some paid a price for their daring protests.

A total of 45 students were arrested: 11 from the first batch, Zay Yah Oo from the second batch and 33 from the third. Most received prison sentences of between five years and seven years. Zay Yah Oo received a five-year sentence and was sent to Katha Prison, in Sagaing Region.

They endured hard times in prison because of their association with the military. Despite being imprisoned for political activities, they were shunned by the political prisoners and suffered, in Zay Yah Oo’s words, an “identity crisis”.

Prison officials also treated them harshly because the Tatmadaw regarded them as traitors. Zay Yah Oo said they were forced to perform hard labour, even though it was not included in their sentences. When he refused, he was beaten by the guards and lost two teeth, he said.

After passing this difficult stage, he found pleasure in reading English classics from a library of about 70 books left at the prison by a Shan sawbwa, or hereditary prince.

After his release from prison in 2006, Zay Yah Oo wanted to work in journalism and joined The International Affairs Journal and then Yaung Chi Moe as a translation editor.

In 2008 he was involved in training some student activists about the new, military-drafted constitution. He was arrested and charged under sections 143 and 147 of the Penal Code for involvement in the September 2007 protests, and sections 6 and 7 of the Unlawful Associations Act for cooperating with the All Burma Federation of Student Unions, an outlawed organisation.

Using disadvantage to his advantage, he continued reading avidly in prison, mainly books about constitutional and federal issues sent to him by friends.

“I would say I am standing on my feet by the knowledge I learnt in prison,” said Zay Yah Oo, who was released under amnesty in 2012.

Since then he has made a living teaching constitutional and federal studies at the Bayda Institute, an NLD-affiliated training school. Last year he was in-charge of the National League for Democracy central research team working group but then left to join the Myanmar Electoral Resource & Information Network, MERIN.

Reflecting on his experience at MTC, he said that the young students were “victims” of a political game. “I think the military wanted to organise young people as soldiers, and offered false incentives to get them to enlist,” he said.

Although his ambition was derailed by his role in the mutiny, Zay Yah Oo has no regrets.

Some of his MTC classmates have achieved success in business and in education and he is proud of them.

“But some became alcoholics and have no future,” he said, sighing.