Days after the arrest of three Eleven Media journalists, the state counsellor says outsiders would be surprised by the level of media freedom in Myanmar.

By SITHU AUNG MYINT | FRONTIER

SEPTEMBER 3 was a black day for journalism in Myanmar. Reuters reporters Ko Wa Lone and Ko Kyaw Soe Oo were sentenced to seven years in prison for breaching the colonial-era Official Secrets Act.

After their arrest in December last year and during their pre-trial hearings and trial, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was sometimes asked about the case. Each time, she invariably said it was about upholding the law and had nothing to do with freedom of expression. In an interview with Japanese broadcaster NHK in June, Aung San Suu Kyi said the two reporters “were arrested because they broke the Official Secrets Act”. Her presumption of the reporters’ guilt before a verdict was handed down in court was condemned by media freedom advocates in Myanmar and abroad.

On October 10, three journalists from Eleven Media were arrested on charges brought by the Yangon Region government over a report published two days earlier in Weekly Eleven under the headline, “Loss-making gas stations, school buses bought with money borrowed from an unknown lender and public shares in individual’s names”.

Chief editor Ko Kyaw Zaw Lin, editor Ko Nay Min and chief reporter Ko Phyo Wai Win are facing charges under section 505(b) of the Penal Code for the alleged publication of incorrect information that could cause alarm. If convicted they face a maximum penalty of two years in prison and a fine.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The report included comments made in the regional parliament by U Tin Win (Union Solidarity and Development Party, Cocokyun-1) about shareholdings in Yangon Metropolitan Development Public Co Ltd. The Yangon Region government holds a 51 percent share in the public-private company, which was incorporated last year to promote development in the region.

Tin Win said shareholders in the company included regional Minister for Planning and Finance U Myint Thaung and Minister of Electricity, Industry, Transport and Communication Daw Nilar Kyaw.

“Because private individual names are used when shares are bought with the government’s public money, it might get lost if something goes wrong,” Tin Win said.

The MP said Myint Thaung held 639,500 shares each worth K100,000 in Yangon Metropolitan Development.

The Weekly Eleven report said that despite the company being established according to corporate regulations, “the largest shareholder is a government minister and lawmakers have pointed out this could lead to complications”.

The report also said it was not appropriate that Myint Thaung was listed as a shareholder by name with no mention of his ministerial position.

After the Yangon Region government decided at a high-level meeting to take action against the three journalists, police went to Eleven Media’s office in Tarmwe Township on the evening of October 9 to arrest them, but they were not there. They were arrested, charged and sent to Insein Prison when they presented themselves at Tarmwe court the following day.

In an explanation of its decision to prosecute, Yangon Region government said in a statement on October 11 that it had taken 539,500 shares in Yangon Metropolitan Development Public Co Ltd when it was established, while 48,600 shares were held by Myanmar Construction and Development Co Ltd, a private company comprised mainly of developers.

The regional government said public property shares were not held under Myint Thaung’s name as mentioned in report. It said alleged misinformation in the report might frighten shareholders in MCD and damage the respect and confidence of the people in Yangon Metropolitan Development Public Co Ltd.

However, a sentence in the statement quoting part of 505(b) has generated confusion. It stated that the report “may damage respect and confidence in the regional government and stimulate the people to commit an offence against the government”. Nobody fully comprehends what this means, but it has been suggested that the wording was included to justify the charges under section 505(b), which has often been used to target activists and journalists, is vague and abstruse.

The Weekly Eleven report was an account of a discussion in the regional Hluttaw. If it is inaccurate, the Yangon regional government should hold a news conference and identify the errors. It could also demand that Weekly Eleven publish a correction or refer the matter to the News Media Council. It could also have taken action under the News Media Law or sued for defamation under section 500 of the Penal Code or sought compensation under civil law. By opting to bring charges under 505(b), Yangon regional government has sought to intimidate the media. Anyone charged under 505(b) is immediately taken into custody, though they can apply for bail. At a pre-trial hearing at Tarmwe court on October 26, the three Eleven Media journalists were granted bail.

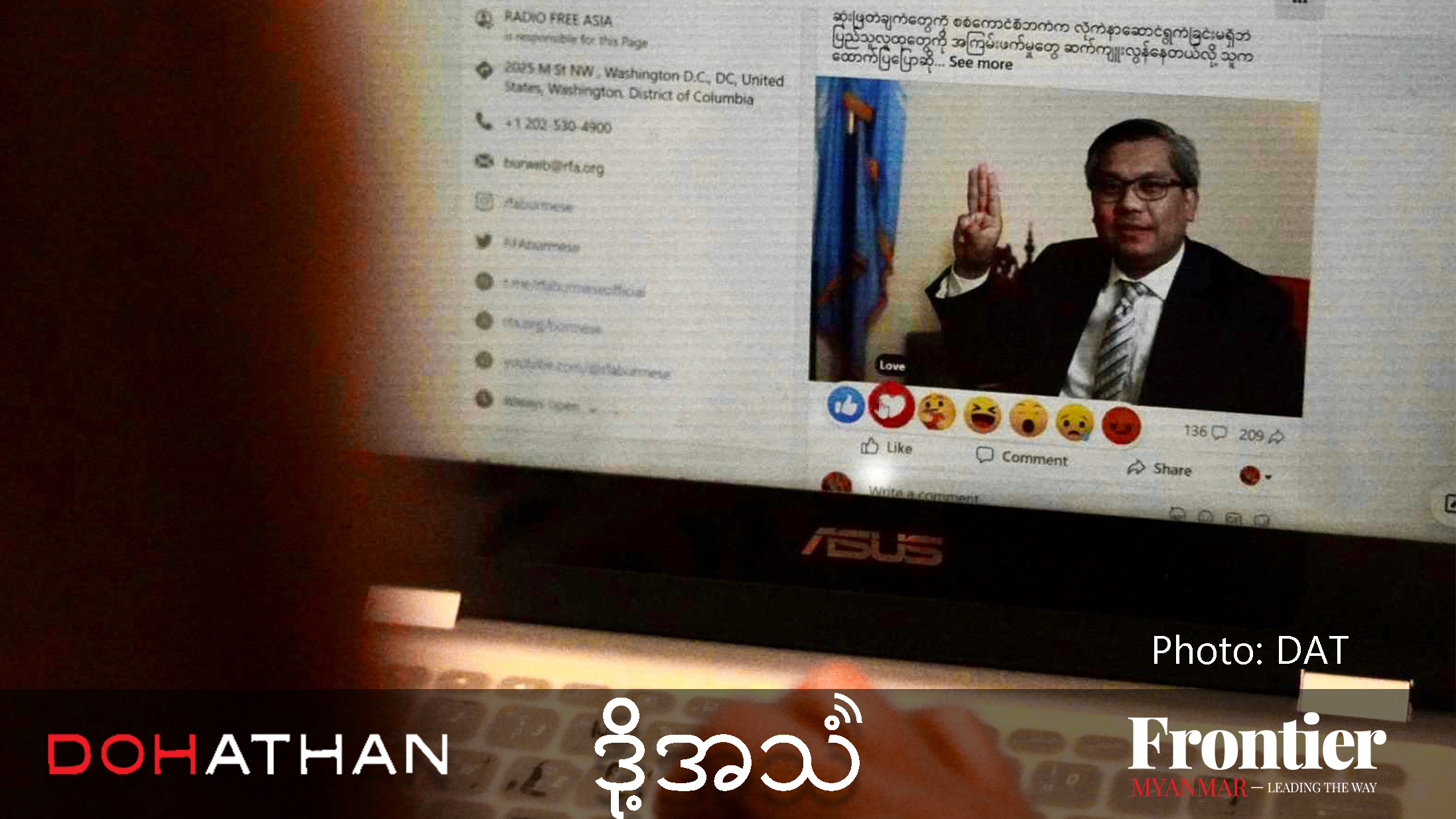

In an interview with NHK on October 8 during her visit to Japan, Aung San Suu Kyi spoke about media freedom in Myanmar.

The state counsellor said that if anyone concerned about the situation in Myanmar studied 24 hours’ output of social media and conventional media they would be “surprised” by what they found.

“They express themselves very freely and very widely on everything from the government to what’s happening next door to them in their street,” she said.

What Aung San Suu Kyi said is correct in one sense – in Myanmar, we do enjoy the freedom to publish what we like in mainstream media or on social media. But, unfortunately, there’s also a chance you will be taken into custody or receive a long prison sentence as a result – the sad case of the three Eleven Media journalists is just further evidence of that. It would be interesting to know what Aung San Suu Kyi has to say about this.