Government-media relations are locked in a vicious cycle. To break it, the government must stop treating journalists as threats to be managed and instead consider them partners in deepening democracy.

By BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

TEN YEARS ago in Myanmar, most citizens desiring news about their country had to sift through teashop rumours, state propaganda, the contents of heavily censored weekly journals and clandestine broadcasts transmitted from abroad by journalists whose access to national decision-makers was inevitably limited. That which the military junta did not tightly control, it sought to ban and suppress.

The government of retired generals that came to power in 2011, and ruled till 2016 under President U Thein Sein, began a series of reforms that dramatically widened political participation and debate – even while many repressive laws and military prerogatives remained in place, making progress uneven and easy to reverse. Media reforms were an important and very visible part of this programme, which helped end Myanmar’s isolation among an international community that was keen for a good news story from a country located on the frontline of geopolitical rivalry between China and the West.

The ending of pre-publication censorship for print media in August 2012, coupled with the dramatic expansion of public access to the internet that resulted from the liberalisation of the telecommunications sector in 2014, produced an explosion in lawfully published information about politics and society. Private daily newspapers were printed from April 2013 and soon ran to more than a dozen, though only half survived past 2016, as news consumption was by then moving increasingly online.

Some of the foundations of a self-regulating media industry were also laid down. The 2014 News Media Law established rights for “media workers” and “freedom from censorship” and the 2014 Printing and Publishing Law extended licences from one to five years. Independent groups like the Myanmar Journalists Association emerged from 2012 and the News Media Council, or “Press Council”, was created with a mandate to mediate complaints against journalists and publications to avoid criminal suits, and to lobby for journalists’ interests.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Up till the election victory of the National League for Democracy party in late 2015, the trajectory was undeniably positive. There was increased access to government, a growing (though still inchoate) culture of reasoned debate, and a new generation of journalists that did not have to make the same compromises, or take the same risks, as the older generation when reporting in the public interest.

Nonetheless, these foundations were shaky in a country where the law courts are easily influenced by the politically powerful, where even well-intentioned laws are frequently too vague and contradictory to protect rights, and where institutions mandated to hold authorities to account are routinely undermined or bypassed.

As the NLD administration got underway, optimism among the press corps diminished quickly. Journalists who had established dependable lines of contact with members of the Thein Sein administration were getting the cold shoulder from members of the newly enthroned NLD, whose victory had been aided by the enthusiastic support of the private media. They also began to see their colleagues arrested and put behind bars at a rate quicker than under Thein Sein.

In the arrest and prosecution of journalists such as Reuters reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were convicted in September 2018 of obtaining official secrets but pardoned in May, the Press Council and the protective provisions of the News Media Law have been impotent. In addition, a range of laws still in place prescribe prison sentences for defamation, meaning that a government official or businessperson who is upset at a “defamatory” article can summon government resources to punish the offending journalist via a criminal complaint.

The NLD has not used its parliamentary majority to change these laws, and while the military’s control of the police and influence over the courts underlies much of the persecution journalists face, NLD members have been a regular source of defamation suits.

Whether the situation for journalists in Myanmar is currently worse than in other Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand and Cambodia, is debatable, but recent setbacks have fed a strong sense of ground being lost in the overall reform process. There is now a more openly wary, and less functional, relationship between the government and the media than under the previous government.

Both local and foreign journalists have very limited access to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who as state counsellor is the key government decision-maker on most policy areas besides security, where the military retains a monopoly. She prefers to engage with the public directly via state media and town hall meetings that nonetheless appear highly stage-managed. Ministers generally defer to Aung San Suu Kyi and are either reluctant or unable to explain policy beyond abstract principles, leaving high-level governance opaque.

Moreover, neither Aung San Suu Kyi nor any official has acknowledged the worsening conditions for journalists. Minister of Information Pe Myint, a former journalist, told a media conference in December 2018 that claims that press freedom was deteriorating were spurious and that reports by groups like Reporters Without Borders are “biased in favour of those who fund them”.

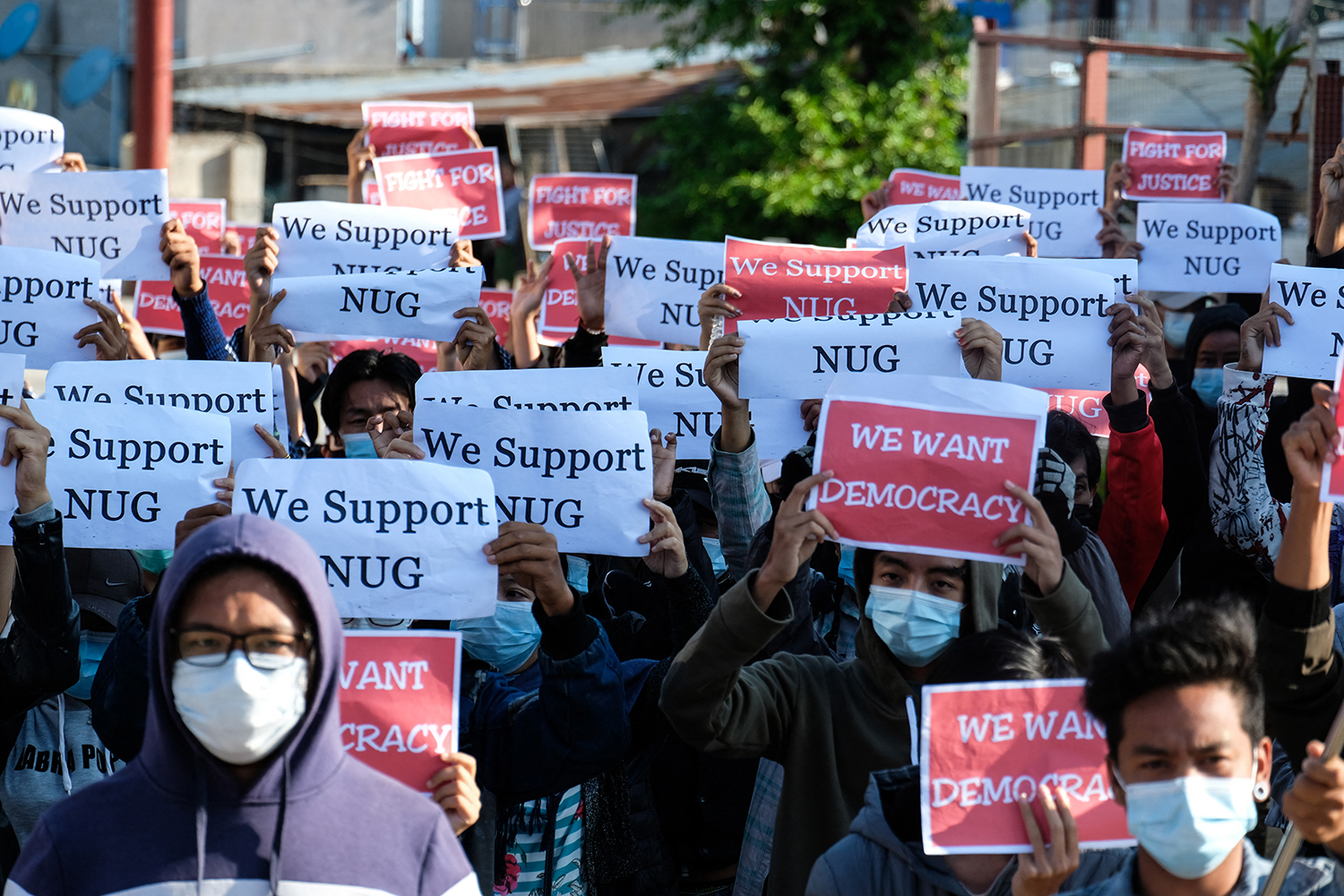

Government-media relations are locked in a vicious cycle, with poor communication feeding distrust and distrust in turn impairing communication. (Hkun Li | Frontier)

This situation presents a paradox: An elected government led by veteran dissidents, who were lionised by international media and supported by people now leading domestic media, seem to view independent journalists as spoilers, to be disciplined or avoided, whereas a preceding government led by members of the old military establishment actively courted them.

One explanation for this hinges on attitudes towards political legitimacy. The 2010 general election that installed the Union Solidarity and Development Party government was derided internationally as rigged and was boycotted by the NLD. The government of ex-generals therefore lacked democratic legitimacy and also had to overcome massive, and well-earned, distrust at home and abroad over their sincerity in undertaking reforms. However calculating the motive may have been, building relations with both Myanmar and foreign journalists was a way of turning the narrative in their favour and broadcasting reformist credentials to the world.

The NLD by contrast conceives of itself as a national movement with an impeccable degree of legitimacy, which was vindicated by its landslide victory in the 2015 election. The party seems to feel that the press, particularly if critical and open to competing agendas, is a barrier between it and the people, rather than a partner. Aung San Suu Kyi and her administration have tried to bypass private media, ostensibly to seek a more direct relationship with the public – but in a way that marginalises critical perspectives and gives the government more control over the narrative, with only token opportunities for the public to talk back.

This strategy is pursued by two principal means, one being social media, principally Facebook, whose reach has grown considerably during the tenure of the NLD government. The State Counsellor’s Office, ministries and even township police departments run Facebook pages that citizens often go to first for information, and public engagements are often live-streamed on the platform. The other means is state media, which in print and broadcast forms continue to enjoy bigger reach and circulation than private media. Being heavily subsidised, it also undermines the financial viability of private media by attracting the lion’s share of advertising, particularly in broadcast, and undercutting cover prices in print.

There was talk during the Thein Sein government, including from information ministers, about transforming state media organs into public service media, and industry figures had called on the NLD to wind down state media. But under the NLD the outlets remain government mouthpieces and their reach is as large as ever. State newspapers Myanma Ahlin and Kyemon dedicate lavish spreads to Aung San Suu Kyi’s public engagements, and to official ceremonies of little real news value.

But it would be unfair to blame the sour state of media-government relations entirely on the NLD’s brand of politics, when the greatest catalyst for the souring of relations was a crisis that would conceivably have prompted greater hostility and repression under previous, military-aligned governments.

The military’s brutal crackdown on the Rohingya in August 2017, which the military insisted was a legitimate response to attacks by Rohingya militants, saw more than 700,000 members of the largely stateless Muslim group flee to neighbouring Bangladesh. The crisis animated prejudices around race and national identity – and the close conjoining of the two – that are both deeply rooted in Myanmar society and central to the way that the military views national security.

The NLD administration had no authority over the military operations in Rakhine State that prompted accusations of genocide from United Nations investigators, but the NLD had to take charge of the public messaging, for both domestic and international audiences, as well as foreign relations as the crisis unfolded.

While international media reports of military atrocities poured in, the civilian government opted for blanket denials. This quickly lost it any influence it might have had over how the narrative played out internationally.

The popular backlash to the global outcry over the Rohingya inspired an aversion towards foreign, particularly Western, media, with narratives of “fake news” serving sinister foreign agendas gaining currency. In this context, state media was instrumental in shaping the domestic narrative around the Rohingya crisis. With independent journalists blocked from accessing northern Rakhine outside of government-guided tours, state media acted as a funnel for information about events on the ground. This information was repeated uncritically by much of the private media and amplified on social media, where heightened fears of Islamist terrorism and illegal immigration inspired a deluge of hate speech.

However, hostility towards the foreign press has not translated into better relations between the government and domestic media, even though the latter largely defended the government over its handling of the Rohingya crisis. In fact, the distinction between foreign and domestic outlets reporting on Myanmar is often fuzzy: many Myanmar-based media groups have foreign links in the form of grants, investment and content partnerships, meaning the government is unlikely to ever trust them in safeguarding its reputation.

At a dinner for new Press Council members in November 2018, Aung San Suu Kyi made disparaging comments about the media, according to people who were present, and even derided a suggestion that better access to information in Myanmar would prevent journalists from being biased. “It made me wonder if she has any trust in the media,” Press Council member U Zayar Hlaing told Yangon-based outlet The Irrawaddy.

The visible lack of respect shown by the government towards the press is a strong signal to the public, and one that leverages Aung San Suu Kyi’s popularity. “If our leader doesn’t respect the media, why should we?” her supporters might ask. When it chooses to, the government is able to direct public opinion against journalists with devastating effect, scapegoating them for tarnishing the reputation of the country or “fuelling” conflict by reporting on discrimination and human rights abuses.

Myanmar reporters now commonly complain of being treated with disrespect by society, and comments on the Facebook pages of media outlets are full of users expressing contempt towards the press. For all the international outrage that the prosecution of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo generated internationally, local demonstrations in favour of their release struggled to attract more than a few dozen participants and the public mood seemed to veer mostly between hostility and apathy towards the two reporters and their plight.

Yet, even the staunchest advocates of press freedom would concede that the standard of news reporting in Myanmar varies enormously. Training is limited, salaries and resources are meagre and publications with decades of independent reporting behind them are absent, resulting in a rough product. The government and the public are in many cases justified in complaining about inaccurate or unbalanced reporting. Nonetheless, one of the main causes of bad reporting is the dearth of information provided by government about even its signature policies.

Government-media relations are locked in a vicious cycle, with poor communication feeding distrust and distrust in turn impairing communication. The government feels that the media misrepresents what they do, and the media feels shut out and disrespected by the government. The government could help break this cycle by investing in a proper communication apparatus; the assets of the Ministry of Information could be reassigned from producing crude propaganda to equipping ministries with press departments capable of communicating promptly with journalists about government positions and briefing ministers before interviews.

But a more collaborative attitude towards the media is not enough by itself.

The NLD administration needs to affirm publicly that an independent media is essential to honest, accountable government, and that the work of journalists deserves respect as well as scepticism. This could help lay the ground politically for the many laws and administrative behaviours that constrain press freedom, and freedom of expression more generally, to be changed – and for journalists to be able to do their work safely, effectively and with the support of society.

This essay was adapted from a presentation Ben Dunant gave at an international workshop, “Fake News and State Control in the Post-Truth Era in Southeast Asia”, at Kyoto University on July 22 this year.