The new Asia Barometer Survey finds greater tolerance of diversity but also growing political division and disenchantment with democracy since the last survey in 2015.

By BRIDGET WELSH & MYAT THU | FRONTIER

No country in Southeast Asia has experienced more intense political, economic and social changes over the past five years than Myanmar. The changes are evident in everything from the Yangon skyline to ubiquitous mobile phone use, from the COVID-19 response to televised debates of parliament.

Despite this, opportunities to quantify broad political, social and economic change remain relatively rare in Myanmar. The Asia Barometer Survey seeks to fill this gap. Its new report details the findings of a nationally representative survey of 1,620 respondents carried out in September and October 2019 through face-to-face interviews across the 14 states and regions (excluding conflict zones).

Significantly, this report is able to compare public perceptions and political behaviour against an earlier study conducted in Myanmar in 2015, and also see how Myanmar fares against other countries in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam (Cambodia and Singapore surveys are ongoing this year). The latest survey reveals an often contradictory but overall worrying picture of democracy in Myanmar.

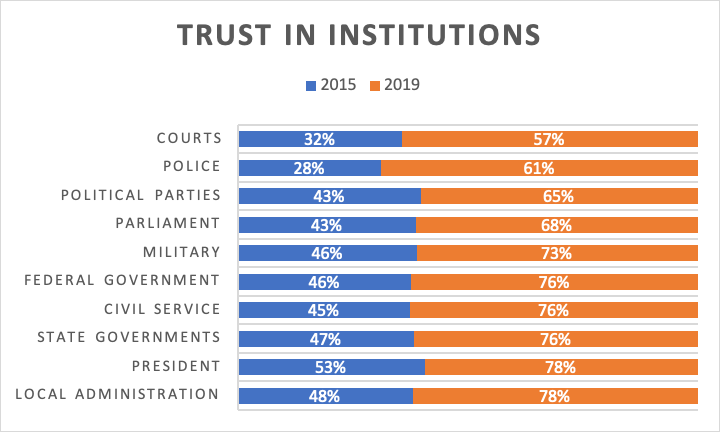

First, though, let’s start with the good news: There has been a significant rise in confidence in political institutions, from the parliament and judiciary to the election commission and police force. This higher trust in political institutions across the board is accompanied by greater confidence in the capacity of government to address the problems Myanmar is facing. In all of the ABS research over the past 20 years, no other country in the 14 East Asian countries/territories surveyed has seen such an increase in institutional trust in such a short period of time. The chart below shows that positive views of trust by institution over the two surveys.

Support independent journalism in Myanmar. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The ABS has also found that perceived tensions over religious conflict have declined compared to where they were four years ago, with 50 percent of respondents saying it had become “less serious”. Citizens are also identifying first with the nation rather than their faith. Religion continues to have a prominent role in political as well as social life, but a reduced one. The past four years have seen a strengthening of national identity and ebbing of religious differences, at least from the perspective of surveyed perceptions. .

We also find that greater openness to the international community has coincided with less defensive nationalism, a drop from results four years ago. Asked whether “more should be done to defend their way of life as opposed to learning from other countries”, 66pc agreed. But contrary to reports, Myanmar is not as nationalistic as other countries surveyed in Southeast Asia, notably Indonesia and Vietnam, despite a majority holding nationalistic views. The ABS comparative findings challenge Myanmar’s negative international brand as resistant to international engagement.

The country’s political transition has brought about some other important shifts in political attitudes and behaviour. Myanmar citizens still have the most conservative political values among countries surveyed in Southeast Asia, but the past four years have also seen the largest decline of these values in the region. Rapid modernisation has led to a value liberalisation in Myanmar society. This shift is not uniform, but two areas where changes are particularly marked are greater acceptance of gender equality and an embrace of individualism.

Myanmar citizens are also understanding democracy differently. In 2015, attention centred on elections – the procedural dimensions of democracy – after decades when citizens could not freely choose their government. Today, there is more attention on good governance and the more substantive dimensions – the deliverables – of democracy. In particular, more than half of Myanmar citizens expressed concern about systemic corruption in both the national government and state and regional administrations – the highest proportion among the Southeast Asian countries surveyed.

Myanmar’s social media explosion has encouraged citizens to engage politics differently. Over a quarter now get their news from the internet and social media, especially Facebook. Although television remains the main news source, the ABS study found that social media is widely used across Myanmar, especially among urbanites and the young. This shift has not yet translated into extensive use of social media and the internet for political participation, however, and the level of trust in the internet and social media in Myanmar is the lowest among Southeast Asian countries surveyed.

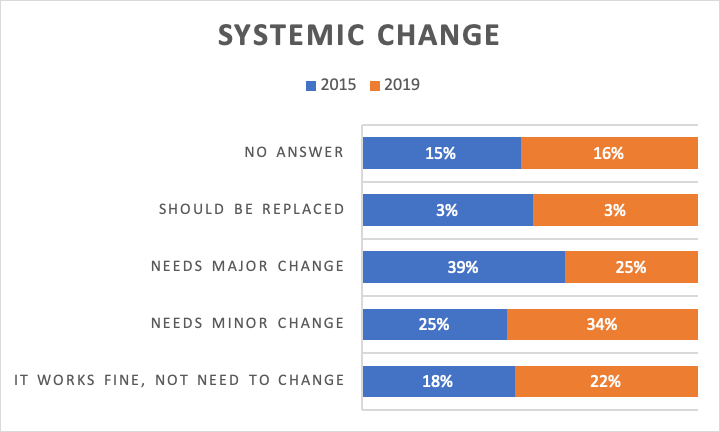

The ABS also revealed widening political divisions in Myanmar society, particularly in three interrelated areas. In 2015 the overwhelming majority of respondents looked to the future and wanted political change. There was considerably unanimity in looking ahead to a shared democratic future. However, over the course of the two surveys, it has become clear that there are stark differences in what respondents believe this political future looks like. When asked about systemic change (see chart below), a quarter seek major reform and a third advocate for minor reform, but also a considerable cohort of nearly a quarter wants no reform at all.

The second involves the role of the Tatmadaw in politics. Echoing the findings of other polling research, the ABS study finds that there is still strong support for the military’s role in politics among its traditional base: those in rural areas, who are religious with traditional values, ethnic Bamar and men. It also finds though that the Tatmadaw is developing a new base of support among younger people, who increasingly see a role for the military in addressing ethnic conflict. Of the three sharpening divides, the political role of the military is the most contentious, with strong views on both sides.

The third division involves views on ethnic autonomy. In 2015, there was strong support for empowering ethnic minorities through a greater devolvement of power. With increased ethnic conflict seen as a serious concern by the public in the ABS – and a stalled peace process, the public is more fractured on this issue. There is a fair degree of support for state legislatures electing chief ministers from states, but fewer than half agreed that ethnic minorities should have more autonomy.

Polarisation over reform, the Tatmadaw and ethnic autonomy is interconnected and mutually reinforcing, with many of the same people taking the same sides on the different issues. While it is too early to argue that Myanmar is a politically polarised society – as in the case in many of the Southeast Asian neighbours – the trend points to growing political divisions that have emerged out of the democratic transition and arguably will be obstacles to greater democratisation.

This is a concern, but there are other findings that give greater cause for alarm. Not only does the majority hold onto conservative values that discourage tolerance and inclusion, but many Myanmar continue to lack political literacy – the knowledge to participate meaningfully in politics. This is especially true in rural areas. Many Myanmar do not understand how a democracy works, and in particular show little support for a system with checks and balances.

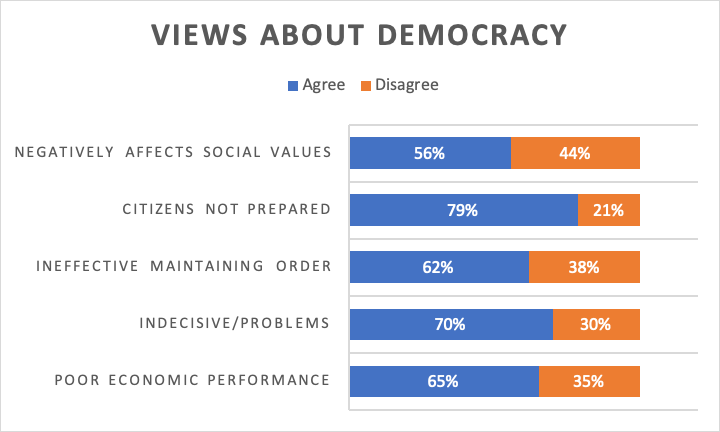

Although support for democracy remains high, the intensity of support has declined. In a reversal of the results of four years ago, Myanmar now has among the lowest support for democracy among the Southeast Asian countries surveyed. Even more worrying is that the ABS study finds many Myanmar have negative views about democracy and how it is (or is not) working (see chart below), tying democracy with poor economic performance, problems, negative social values and lack of maintaining order. In particular, many believe their fellow citizens are not prepared for democracy.

The rapid modernisation of Myanmar has, ironically, eroded the networks and trust seen as important to building democracy. The study reveals that social capital – the ties that tie society through members joining organisations and forging relationships – and trust have declined.

There has been a sharp drop in people’s belief in their political efficacy, with more Myanmar citizens believing that they cannot impact politics. Non-electoral participation remains low. In the one area where Myanmar citizens participated in politics outside of elections – solving local problems – there is a marked decline.

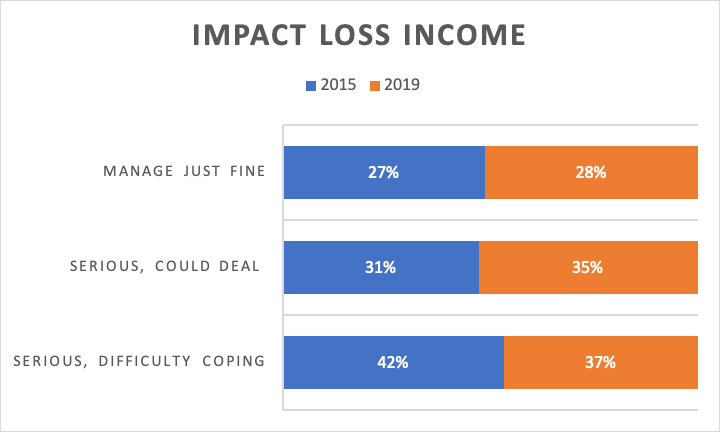

These concerning trends in political attitudes and behaviour are overshadowed, however, by the dominant concern of Myanmar citizens: the economy. Despite strong growth since 2011, most ordinary people do not perceive changes in economic conditions positively because this growth is not being felt on the ground. In fact, there are worrying reports of persistent precarity, as many are vulnerable and struggling to adjust to a more competitive economy. The chart below reports how respondents would be able to manage if they lost their income, with over a third pointing to difficulty in coping. The ABS was conducted before the emergence of COVID-19, which will only serve to exacerbate economic issues further.

The challenge ahead is not only to engage the different worrying findings in the report individually but to appreciate that views about the economy, concerns about social capital, trust and conflict in society, and greater division over politics reinforce each other. Over the past five years, Myanmar has seriously grappled with transition, which is the focus of the ABS report. At the same time, the findings also show that it is grappling with democracy.

The full report can be read here.

Dr Bridget Welsh is a honorary research associate at the Asia Research Institute of University of Nottingham Malaysia. She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democracy of National Taiwan University and served as senior advisor for the 2015 and 2019 Myanmar Asia Barometer Survey.

Myat Thu is the chairperson of the Yangon School of Political Science, which was founded in 2011. A Chevening Scholarship awardee, he received a masters in political theory from the London School of Economics and Political Science in 2013 and was a visiting scholar at St Anthony’s College in 2018. As founder of the Myanmar Political Science Association he works to promote the understanding of politics and democracy.