The residents of Myanmar’s poorest state are hoping the National League for Democracy government will overturn years of neglect that some say is the result of religious discrimination.

By OLIVER SLOW | FRONTIER

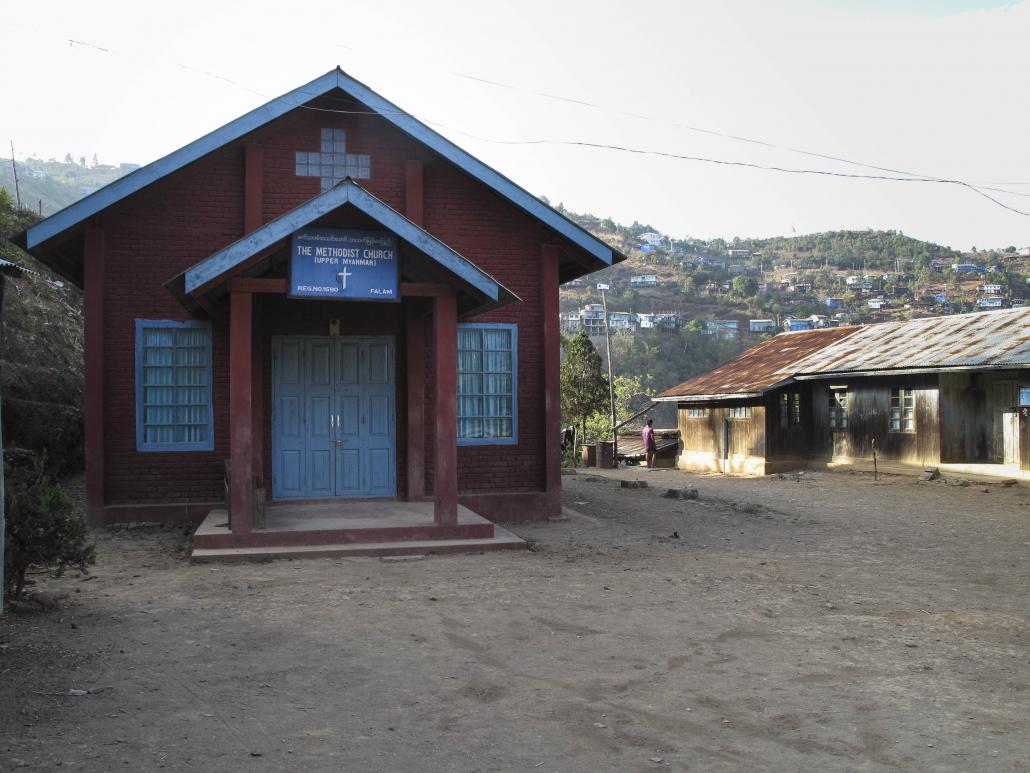

It is only about 80 miles from Kale in Sagaing Region to Falam in poor, mountainous Chin State, but the journey takes at least six hours, more if roadworks cause delays, which are common.

Six hours is a big improvement on previous years, said Salai Thawn Lian Than, a civil society leader and youth pastor at the Gospel Baptist Church Church in Falam, a picturesque town about 20 miles north of the state capital, Hakha.

“You would often have to stop somewhere to sleep on the way,” he said, adding that improvements to the road had begun after the change of government in 2011.

Apart from upgrading the road, the changes that have brought improvements to much of the rest of the country since 2011 have barely affected Chin, the poorest and least developed of the nation’s 14 states and regions.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The poverty and lack of development are underscored by data from the 2014 census.

Oliver Slow / Frontier

It shows that 73 percent of Chin’s 478,801 people live below the poverty line, the highest rate in the country and nearly double the 44 percent in neighbouring Rakhine, the next poorest state or region.

Chin, the second least populated state or region after Kayah, consistently ranked near the bottom in other social indicators.

It had the third lowest literacy rate, after Ayeyarwady and Kayin; the third highest infant mortality rate, behind Ayeyarwady and Magway, and the third lowest life expectancy at birth (63.6), after Ayeyarwady (61.0) and Magway (60.6).

Census data also shows that the unemployment rate in Chin, 5.4 percent of those aged between 15 and 64, is the fourth highest in the country, after Rakhine (10.4 percent), Kayin (7.5 percent) and Mon (6.2 percent).

Civil society leaders in Falam say unemployment is a big issue.

All of the families interviewed by Frontier for this report had relatives working abroad because of limited job opportunities in Chin.

“I have just come back to try and find work, but there is nothing here,” said a young man named David who had recently returned from studying in the Philippines. Asked what he planned to do next, he shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t know, maybe leave again,” he said.

During Frontier’s visit to Falam, the town’s water supply had been out for days. There was electricity for only a few hours a day.

Young children in Chin State. (Oliver Slow / Frontier)

Thawn Lian Than pointed to an electricity pylon on a hill above the town. “They [the government] tell us we will have electricity soon. But nothing yet,” he said.

Many Chin believe their state has been neglected by the Union government and that the main reason is because they are predominantly Christian.

“We call it the double C virus – Chin Christian – if you are double C, you cannot do anything in this country,” said Salai Nhgepi Thian Uk Than, also known as Jack, the chief editor of the Chinland Herald newspaper.

“You cannot be promoted in jobs, you cannot get scholarships for schools and you cannot move up in government jobs,” he said.

Frontier interviewed six church leaders, all of whom told of encountering government restrictions in the past if they wanted to build churches, although they all said the situation had improved since 2011.

“We have no support from the government,” said Thaw Lian Than, a member of the Falam Youth Association, a civil society group. He pointed to a pagoda on a hill overlooking Falam, which is 90 percent Christian. “The Buddhists have support to build pagodas, but we have none. If we want to build a church, we need so many different permissions, even from Hakha.”

The National League for Democracy performed well in Chin last November, winning 12 of the 24 seats in the state assembly, and most of the state’s 15 seats in the Union Parliament.

Pa Chung Bik, the Chin State secretary of the Union Solidarity and Development Party, rejects criticism by many Chin that the previous USDP government did little to develop the state.

The USDP tried to make changes, said Chung Bik, a Chin.

“The USDP worked for the development of Chin State. I think now the NLD is elected, they will make development a priority… The number one priority needs to be transportation,” he said, adding that Chin is the only state or region without an airport.

“And they have to create jobs. There are no jobs available in Chin State.”

Oliver Slow / Frontier

The overwhelming victory of the NLD, that is regarded by some as being pro-Bamar, has produced mixed reactions about how it will govern in the ethnic states.

When the NLD named a Chin, Pa Henry Van Thio, as its vice-presidential nominee, it was regarded by some as an indication that party leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi takes ethnic, and Chin, priorities seriously. Others saw the move as a token gesture.

“The vice president [being Chin] is not a big deal. He doesn’t have any real power; it is just a ceremonial role,” said the Chinland Herald’s Jack, who was unsuccessful as the Chin National Democratic Party’s candidate for a state assembly seat in Falam last November.

Jack said he distrusts the NLD because he regards the party as a “dictatorship”.

He said the scale of the NLD’s victory was a surprise, “but we learned later that people didn’t vote for their policies, they only voted for Aung San Suu Kyi. We will wait and see [if the NLD makes ethnic issues a priority], but I’m not so sure.”

I asked Jack why he seemed the distrust the NLD.

“It’s not the NLD I don’t trust, it’s the Burmese [Bamar]. Historically, we have been oppressed by them,” he said.

One of Jack’s biggest grievances is the quality of education in Chin.

“Chin State is not only the poorest state in the country, it also has the lowest pass rate for the matriculation exam. We have the highest teacher to student ratio in the country, but the lowest pass rate, how can that be?”

Jack believes the low matriculation pass rate contributes to a vicious cycle in which Chin students who fail the exam are unable to become teachers. He says the Bamar teachers sent to Chin by the Union government have no understanding of local customs and culture.

“The government has changed, but we are not so sure if other things will change,” Jack said. “Some think things will change, others are not so sure. But what is sure is that we need to be equal in terms of opportunities, in terms of jobs and in terms of religion.”

Cheery Zahau, an ethnic Chin human rights activist, urged the NLD to prioritise a development plan that is focussed on Chin State, and not one that is made in the corridors of the capital, Nay Pyi Taw.

“Regarding development in Chin State, it will depend on the Chin State government whether they come up with a proactive economit development plan that is feasible to both the state and Union governments,” adding that her party, the Chin Progressive Party, for which she ran in Falam in the November election but lost to the NLD, has developed an economic plan for the state.

“Chin State needs nearly everything from education, health services to economic development. If we are going to boost up the economic development in Chin State, we need to include women at all levels,” she said.