Hanged at Insein Prison in 1976, the only student activist to have been executed under junta rule, Salai Tin Maung Oo’s last words on the gallows were: “I will never kneel down to your military boots!”

By HTUN KHAING | FRONTIER

ON MARCH 22, 1976, Salai Mya Tin, then an 18-year-old student in the second year of a physics major at Rangoon University, was listening with his family to the 8pm news on state radio.

Private media organisations were banned under the socialist regime of the Ne Win dictatorship and state radio mainly broadcast dreary government propaganda.

That evening’s news bulletin included information that shocked the family: Mya Tin’s older brother, Salai Tin Maung Oo, 25, had been arrested by Military Intelligence.

It was the first time the family had heard of Tin Maung Oo in more than a year. He had gone underground after participating in student-led protests that erupted after the body of former United Nations secretary-general U Thant was returned to Burma from the United States in December 1974. He had died in New York the previous month, aged 65.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Students were enraged by the refusal of the Ne Win regime to allow a state funeral for the respected international statesman, who had served as the third UN secretary-general for 10 years until December 1, 1971. Student activists seized U Thant’s coffin and placed it in a makeshift mausoleum at Rangoon University. Troops and police stormed the campus early on December 11 to retrieve the coffin, which was interred early the next day at the Kandawmin Garden Mausolea on Shwedagon Pagoda Road. The violent operation triggered protests in Yangon that led to the imposition of martial law.

Tin Maung Oo was arrested in Yangon on March 22, 1976. He had returned to the capital to lead celebrations on March 23 marking the 100th anniversary of the birth of Thakin Kodaw Hmaing, one of the greatest Burmese poets, writers and nationalist leaders of the early 20th century, who died in July 1964.

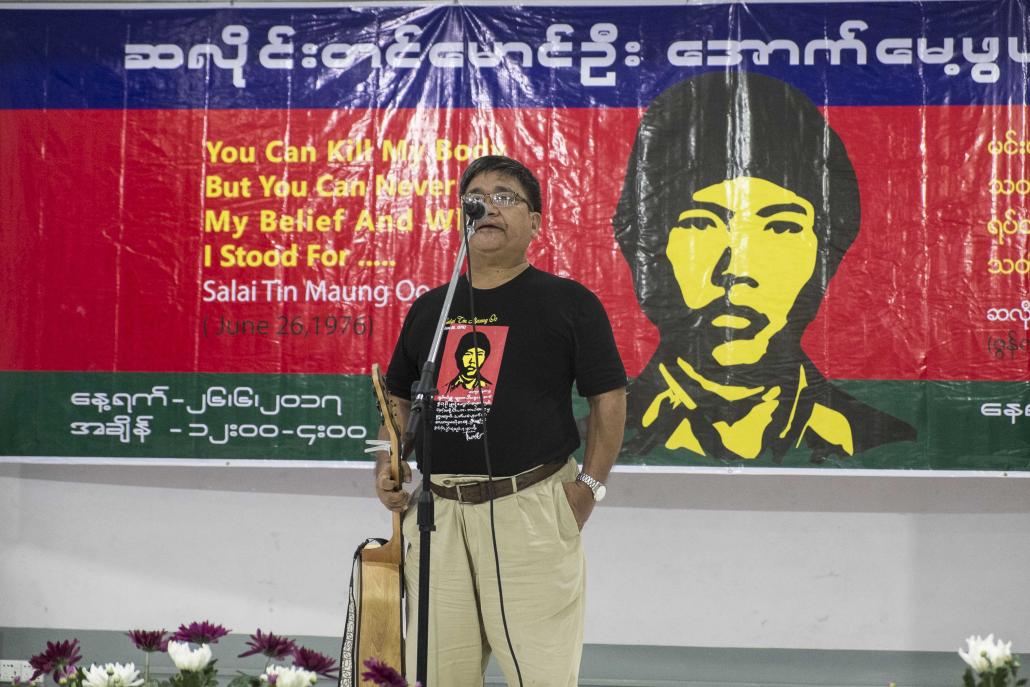

A ceremony to mark the 41st anniversary of Salai Tin Maung Oo’s execution was held in Yangon on June 26. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

At Mya Tin’s suggestion, his younger brother, Ko Hla Shwe, and sister, Ma Hla Myaing, attended the celebrations in Tin Maung Oo’s place.

The next day, Mya Tin’s father, a former Tatmadaw officer, and his mother, a nurse, were also detained by Military Intelligence and taken to Insein Prison.

Mya Tin left the family home in Hlaing Township to tell Hla Shwe and Hla Myaing that their parents had been taken away by Military Intelligence. Soon after Mya Tin returned home, where he needed to care for three young siblings, all aged under 10, he was also detained by Military Intelligence, as were Hla Shwe and Hla Myaing.

Three days later, Mya Tin was sent to Insein Prison and held with other students. He did not see Tin Maung Oo, his parents or his younger brother and sister while he was at the prison.

On the morning of June 25, 1976, after spending three months in Insein, warders told Mya Tin to pack his few belongings.

“I thought I was going to be released because I had done nothing wrong,” he told Frontier on July 1.

When Mya Tin emerged from the prison he saw his father and Hla Shwe for the first time in three months. They all had an escort of armed guards. Mya Tin knew then that he was not about to be released.

They were put in a vehicle for an unknown destination.

“They did not give us anything to eat or allow us to talk so I was unable to ask my father and Hla Shwe if they had news about my mother and Tin Maung Oo,” Mya Tin said.

After a long drive they arrived at Taungoo Prison in Bago Region, where they were held in separate cells.

Mya Tin was to learn later that his mother and Hla Myaing had been transferred under guard from Insein to Thayawady Prison in Bago Region the same day.

The transfer of family members to other prisons came a day before Tin Maung Oo was hanged in secret at Insein on June 26, 1976. He is the only student activist to have been executed under junta rule.

In a report in 2009 marking the 33rd anniversary of Tin Maung Oo’s execution, the online Chinland Guardian said he was regarded by student activists, colleagues and friends as a “big lion” because of his loyalty, leadership and selflessness in the struggle for democracy, freedom and justice.

Tin Maung Oo was also lauded in a statement released for the 33rd anniversary by the All Burma Federation of Student Unions.

“Salai Tin Maung Oo was fighting against the military regime to gain freedom and justice not only for the Chin people but for the whole country. Therefore, he was a heroic martyr in the battle for democracy in Burma,” the statement said.

Tin Maung Oo was defiant to the end. The authorities offered to spare his life if he requested clemency in an appeal in which he agreed to abandon political activism and admit that the protests in which he was involved against the socialist government were wrong, but he refused.

His last words to his executioners were: “You can kill my body but you can never kill my beliefs and what I stood for. I will never kneel down to your military boots!”

An audience member at the ceremony to mark the 41st anniversary of Salai Tin Maung Oo’s execution. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Mya Tin said Tin Maung Oo did not receive a fair trial and that the authorities covered up the news of his execution. It was almost certainly one of the reasons why family members were transferred to other prisons the day before the execution. Mya Tin only learned of his brother’s fate seven months later, when he was transferred from Taungoo to Insein Prison in January 1977.

The execution of Tin Maung Oo instilled fear among activists, Ko Min Ko Naing, a leading member of 88 Generation Peace and Open Society movement, said at a ceremony in Yangon on June 26 to mark the 41st anniversary of the young revolutionary’s death.

“We were so frightened when we learned about the execution of Tin Maung Oo; I was terrified that I would be executed if I protested against that unfair [Ne Win] regime,” Min Ko Naing said.

Tin Maung Oo is regarded as a hero by activists because of his role in protest movements, Min Ko Naing said.

As well as losing a brother and a son, the family also suffered because of its persecution by the Ne Win regime.

Mya Tin had a leg amputated because he did not receive adequate health care in prison.

“They tried to crush the whole family; they were very cruel,” he said.

After spending seven months in Taungoo Prison, Mya Tin was sent back to Insein.

At a summary trial, Hla Myaing and Hla Shwe were each sentenced to prison for seven years. Their parents were each sentenced to five years’ imprisonment, but Mya Tin was released.

Mya Tin believes it’s possible that one of the reasons his brother was executed was because the family was ethnic Chin.

Chin State has long been one of the country’s poorest areas and many of its young men joined the Tatmadaw during the socialist government to make a living.

Mya Tin said Ne Win was furious that the son of a former Tatmadaw officer was working to overthrow his socialist regime. Perhaps there was also concern about the influence that Tin Maung Oo might have over Chin troops in the Tatmadaw.

“All Chin people know about the execution of Salai Tin Maung Oo,” Mya Tin said.

After their release from prison, Mya Tin’s parents had to struggle to make a living.

“Many families such as ours were devastated for daring to resist dictatorship,” Mya Tin said. “I know the current government has much work to do, but I am still looking forward to my brother receiving the recognition he deserves.”

TOP PHOTO: Salai Mya Tin holds a portrait of his brother, Salai Tin Maung Oo, a student activist hung in 1976. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)