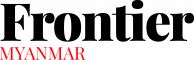

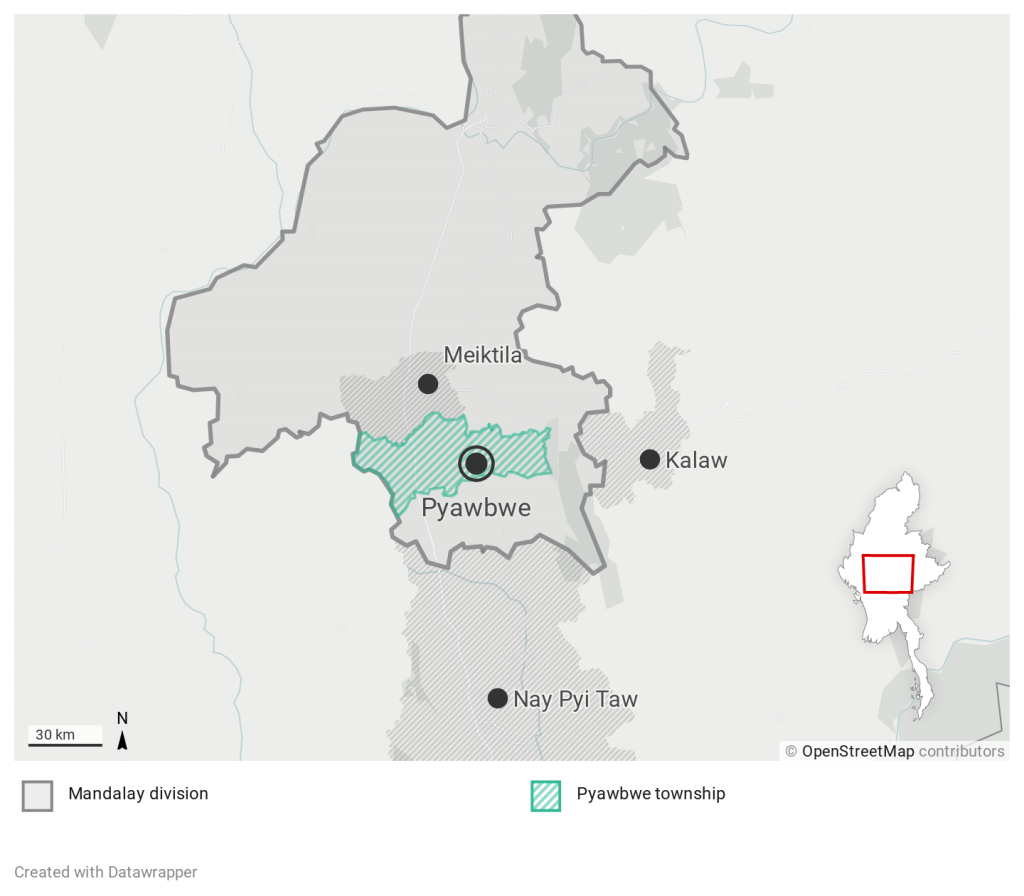

In the Union Solidarity and Development Party stronghold of Pyawbwe Township, in southern Mandalay Region, there is growing anxiety the election will be marred by communal unrest.

This article is part of Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We’re following the election through five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the campaign, voting and declaration of winners. Scroll down for the first two articles on Pyawbwe.

By SWE LEI MON | FRONTIER

Voters nationwide are worried about coming into contact with the coronavirus at polling stations on November 8. But in Pyawbwe Township, that risk is overshadowed by rumours of pending communal violence.

These rumours revive traumatic memories from the 2015 election among the southern Mandalay Region township’s Muslim residents, who were targeted then by Buddhist nationalists. On the night before election day, pamphlets were distributed along roads and near polling stations throughout the township urging voters to shun the National League for Democracy and vote for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, which would protect Buddhism against an alleged Muslim threat. The mysterious pamphlets coincided with a barrage of Facebook posts accusing the NLD of being anti-Buddhist.

Pyawbwe is one of the few Dry Zone strongholds of the USDP, which though weak nationally still draws support from Buddhist nationalists in southern Mandalay Region. Many assume that local Muslims vote NLD, making them even more of a nationalist target.

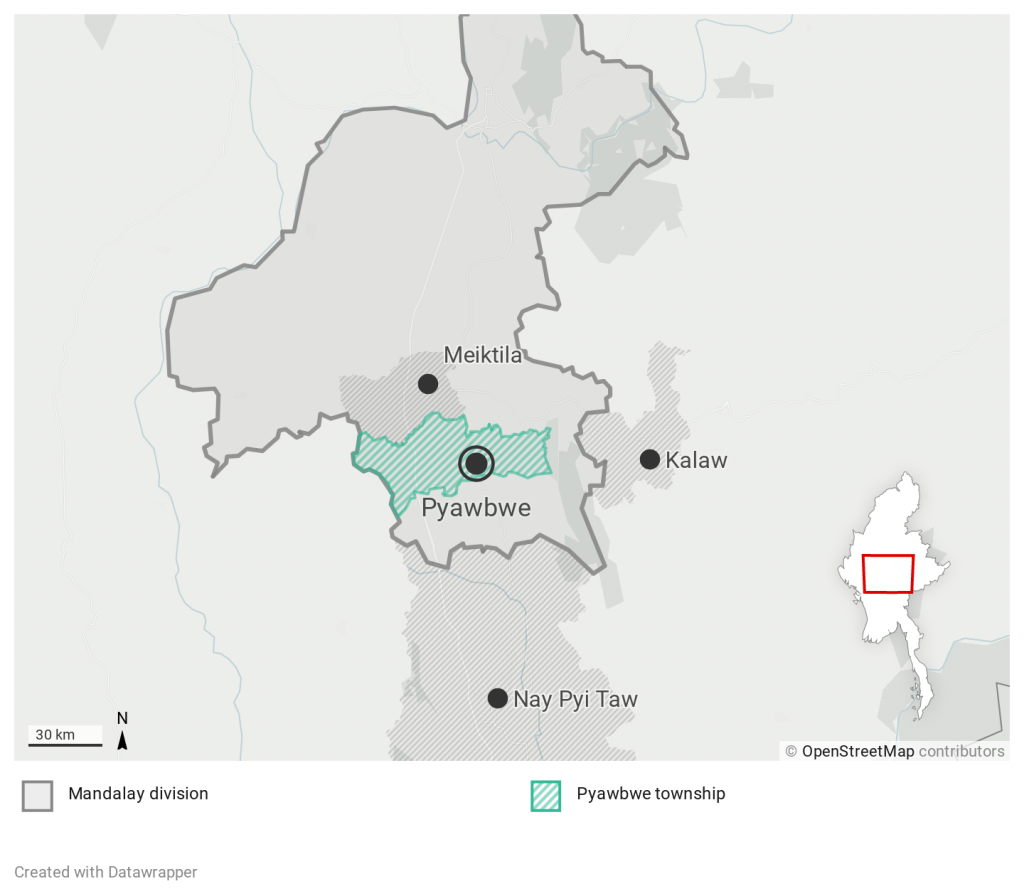

The USDP achieved a clean sweep in Pyawbwe in 2015, winning both seats in the regional parliament as well as the Pyithu Hluttaw seat and the Amyotha Hluttaw seat of Mandalay-10, which encompasses Pyawbwe and neighbouring Yamethin Township.

Ko Nay Zar Linn, one of five Pyawbwe-based members of the Peace Forum Network, a national initiative to support the peace process, recalled one of the most disturbing rumours from the election campaign in 2015 – that one of the nation’s most revered Buddha images, at Mandalay’s Mahamuni Pagoda, had cried tears of blood. This was interpreted as meaning that Buddhism would be tarnished if the NLD won the election.

“That rumour had a huge impact on villagers because of their incomplete knowledge of Buddhism. Then, on their way to vote, they found the pamphlets. The rumours and the pamphlets changed voters’ mindset,” said Nay Zar Linn, a Buddhist NLD supporter.

“Time for change? Of course it is time to change, but not with the NLD”, the pamphlets read, referencing the NLD’s 2015 slogan.

“The USDP government is not perfect, but it is not as bad as the kalar party”, it continued, using a term that is widely considered derogatory for people of South Asian descent, particularly Muslims, to refer to the NLD.

The NLD and its supporters strongly believe that the party lost in Pyawbwe because of the rumours and the pamphlets. The USDP denies this, and allegations that it won in Pyawbwe because of help from Buddhist nationalists.

U Thaung Aye, who is seeking re-election to the township’s Pyithu Hluttaw seat for the USDP, told Frontier in late August that voters supported the party in 2015 because of the incumbent MPs’ strong record of service to local constituents.

“It was not because of Ma Ba Tha or other nationalists,” he said, referring to the Burmese acronym for the ultranationalist Association for the Protection of Race and Religion. The group was banned by the nation’s supreme authority representing the monkhood, the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, in May 2017.

Ko Thatoe Swe, head of the NLD’s youth committee in Pyawbwe, said the possibility of heightened religious tensions around the vote is more worrying than the threat of COVID-19.

“In early October, we heard some rumours about Buddhist-Muslim unrest in the town. Those rumours have gone quiet but we remain concerned as election day nears and are monitoring the situation,” he told Frontier on October 30.

He said that, as far as he knew, no one in Pyawbwe was planning not to vote because of COVID-19, and NLD supporters are optimistic they can reverse the local result of the 2015 election.

The township’s election sub-commission is also aware of the rumours.

“We have heard those rumours often in town, but what can we do to control them?” said sub-commission chair U Soe Myint.

Ko Pyae Phyo Thu, a member of the Pyawbwe Youth Network, a civil society group, said that although residents of Yangon and other big cities were fearful of COVID-19, few worried about the virus in the township, where there have been zero confirmed or suspected cases.

“There is no concern about the risk of COVID-19 while voting, but some residents are disappointed by the crowds at campaign events,” he said.

But, he said, some teachers who will serve as polling station officers have voiced concerns to the sub-commission about the virus and their health, he said.

“The head of the township education department has explained to them that, as government employees, they have a duty to perform the roles they are assigned to, which includes working the polling stations. We’ve tried to help by adding a lot of graduates to the polling station staff to ease some of the burden on the teachers,” Soe Myint said.

He said however that the need to follow health guidelines to limit the spread of the virus had made the work of poll officers much harder than in 2015. The challenges include making sure people vote during their assigned shift on election day – a measure to reduce crowing that will be implemented across the country.

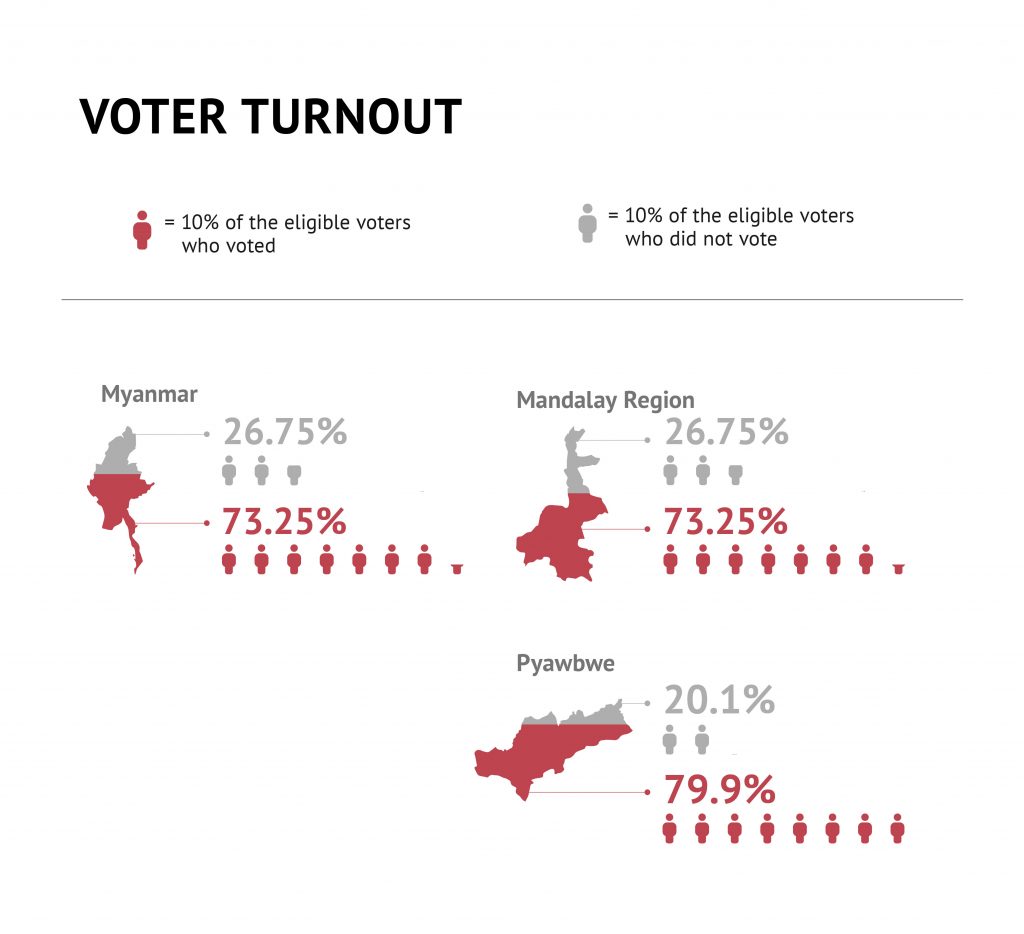

The Pyawbwe sub-commission has prepared a total of 296 polling stations for the township’s 213,823 eligible voters, who will be choosing from among 20 candidates representing seven parties.

“The UEC directed polling station officers to wear full PPE beyond just face masks and shields, which will be very uncomfortable in the heat, but the health department has said it is not necessary, so we are still in discussions about it,” Soe Myint said.

Thatoe Swe said that were concerns that, once advance voting began, violence might flare up between NLD and USDP supporters, as it has in neighbouring Meiktila Township during the campaign period.

In townships elsewhere in the country with a higher count of COVID-19 infections, in-constituency advance voting began in the last week of October for voters aged over 60 and has been hampered by numerous allegations of misconduct and mismanagement, including the use of unauthorised stamps and the issuing of incorrect ballot papers in some areas.

But so far, Thatoe Swe said, “everything seems to be fine, and there have been no disputes among the parties about the voting process.”

Voters in Pyawbwe will be hoping this peace will keep until the results are in, and beyond.