NGO Turquoise Mountain is planning to restore one of downtown Yangon’s most prominent – and historically significant – colonial-era buildings, opening it up to the public once again.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

THE LOCKED gate facing Yangon’s Mahabandoola Park opens onto a cavernous interior. Pigeons roost high up among the cast iron beams that support the ceiling, more than 6 metres (21 feet) above the floor. Small piles of broken masonry, dirt and other rubbish have been swept neatly into piles, on top of imported tiles from the beginning of the last century.

Today, the ground floor of the former Ministry of Hotels and Tourism building – all three floors, in fact – is almost empty. The only occupants at 77-91 Sule Pagoda Road are a few security guards and their families.

On a wall facing the entrance gate, faded and cobweb-covered metal letters spelling “Myanmar Travels and Tours” are the only clear indication of the building’s provenance.

For U Tin Win, the tourist counter that once sat below those stylised letters was a source of excitement – and endless headaches. As operations manager and later sales manager at Tourist Burma, the state-run tourism agency during the socialist era and predecessor to MTT, his job was one of constant problem solving.

dsc_6867.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Steve Tickner / Frontier

Due to the lack of almost any tourism infrastructure, such as hotels, buses and aircraft, arranging even the most basic services for foreign visitors was difficult. Tourists would often be bumped off flights by VIPs. Tourist Burma had only four cars and one bus, so if multiple groups visited at the same time, there was not enough transport available. Communication with the outside world was by telex or phone, but the latter rarely worked.

“We were solving problems from the early morning to the night, every day,” said Tin Win, who resigned in 1991, after 14 years at the state tourism agency, to start his own company. “But we enjoyed it. At that time I was only 25 or 30, so we tried very hard to solve the problems of the clients … but the government never really supported our efforts.”

At the tourist counter, he would help foreigners who wanted to buy air or train tickets, or give them advice on how they should spend the seven days their visas would allow them in the country.

“We didn’t have many problems, but some [customers] weren’t very patient. They would get angry when they couldn’t get an air ticket because they only had a few days and wanted to go to Bagan,” he told Frontier.

dsc_6898.jpg

The building’s rooftop offers unparalleled views of Sule Pagoda, City Hall and Mahabandoola Park. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

From his office, Tin Win also had a front-row seat to some of the largest protests during the 8-8-88 anti-government uprising. City Hall, which sits just across the street from his building, was a significant landmark during the protests and when security forces began firing on demonstrators, they streamed into the building’s foyer, he recalled.

On August 10, 1988, the government – then headed by the despised U Sein Lwin, dubbed the “Butcher of Rangoon” – ordered Tourist Burma to remove all foreign visitors from the country as soon as possible. Tin Win was tasked with contacting all licensed hotels in the country, at Yangon, Bagan, Mandalay, Taunggyi and elsewhere, and instruct them to send their guests back to the then-capital.

When he got between 100 and 150 tourists together, he arranged a Thai Airways charter flight to take them to Bangkok.

“I spent seven days in the office, I didn’t even go home – we would cook our dinner at the office,” he said.

Today, the former Ministry of Hotels and Tourism building that housed Tourist Burma and MTT is a shadow of its once grand self. Vacated barely 10 years ago when the ministry shifted to Nay Pyi Taw, it has deteriorated rapidly due to lack of maintenance, including broken windows and a leaky roof.

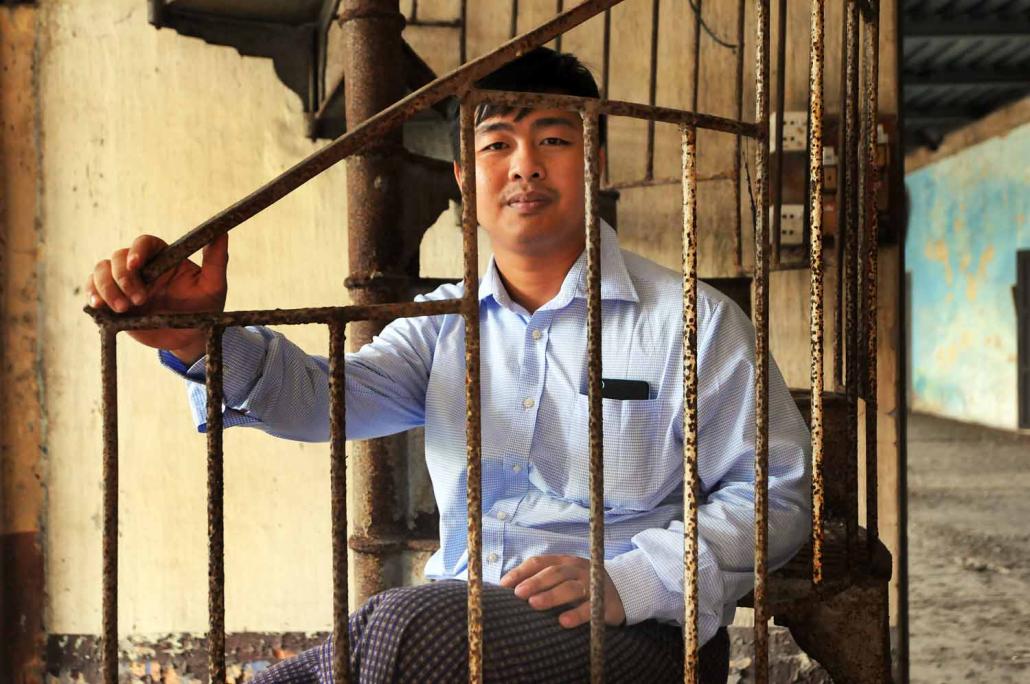

dsc_6925.jpg

Turquoise Mountain project engineer Ko Ko sits on a spiral staircase inside the former Ministry of Hotels and Tourism building. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

The elaborate spiral staircases are heavily rusted, and back rooms are filled with discarded ceiling fans, light switches and lamps – all original, some nearly 100 years old. They are not junk though, far from it.

“We should be able to reuse all of these,” said Ko Ko, a project engineer with NGO Turquoise Mountain, as he flicked a colonial-era light switch. He pointed to a similar-looking switch next to it. “This is from later – it’s made in Myanmar, probably in the 1970s.”

The historic building has a 90-metre (295-foot) frontage onto Sule Pagoda Road, and majestic views from its rooftop over Sule Pagoda, City Hall and Mahabandoola Park. Crucially, the brick and mortar building is structurally sound and may have its best days ahead of it.

Restoration plans

Turquoise Mountain was formed in 2006 to restore a historic district of Kabul, Afghanistan. In April this year, in collaboration with the Yangon Heritage Trust, it completed its first work in Myanmar, renovating a century-old apartment building on Merchant Road. The project was described as a “living restoration” in which residents remained in the building while work was carried out, and retained their apartments once the work was completed.

For its next Myanmar endeavour, Turquoise Mountain planned to take a vacant or underused state-owned building and establish a preservation trust that would be granted a long-term lease to renovate and manage it. The premise was for the building to have a mixture of uses; the priority would be on a public space, but it would also have a business model that would attract potential investors.

dsc_6814.jpg

Today, the derelict interior of the building is empty apart from a few security guards and their families. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

The organisation initially had its eye on several buildings on the lower block of Pansodan Road – home to some of the grandest colonial-era buildings in the city – but Yangon Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein instead suggested the former Ministry of Hotels and Tourism building.

Aside from its history and condition, the relatively straightforward ownership status – by Yangon standards, at least – made it attractive. Although it had been nationalised, the descendants of the original landowner had also donated their claim to a local mosque, which was amenable to non-commercial redevelopment. When the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism left in 2005, it had handed the building over to the Ministry of Construction, which meant it was under regional government control.

Some work has already begun. Turquoise Mountain’s Myanmar director Mr Harry Wardill said some initial survey had been completed with the support of a British architecture firm. Renovation work is expected to begin in June 2017 and run for about two years. It will see about 1,000 people trained in traditional building and restoration skills.

Phyo Min Thein has also given provisional sign-off on the group’s proposed use for the site. Under Turquoise Mountain’s vision, on the ground floor, where Tourist Burma and MTT once ran their information centres, will be a visitors’ centre targeting local and foreign tourists.

dsc_6939.jpg

Steve Tickner / Frontier

The level will also feature a handicrafts centre and an affordable food hall. The middle floor will host an urban design centre featuring a scale model of Yangon, which could serve as a hub for the construction sector. Open-plan office space and a rooftop restaurant will help to drive revenues, but about two-thirds of the building – including the roof – will remain publicly accessible under the plan, Wardill said.

“The idea with [the roof] is that it would be a rooftop public garden that’s got amazing views out over Sule Pagoda but also [Mahabandoola] park. It would be great to make that feel like a public recreation space,” he said.

The service road at the front will also likely be used as a public space, possibly for vendors, markets and exhibitions.

Turquoise Mountain wants the renovated building to be “a space that people feel comfortable coming into”, Wardill said. “We’ve been thinking quite hard about how to actually achieve that – it’s one thing to say it and it’s another to actually achieve it.”

dsc_6821.jpg

Steve Tickner / Frontier

Wardill said it could also become an important example of how Yangon’s historic buildings could be repurposed in a way that’s both financially viable and inviting to the community.

“This will definitely be a kind of subsidised model – as in, we’d probably raise some charitable money alongside investment – but it’s a kind of the right direction to prove the economic viability of these buildings,” he said.

“[We want] to try and get true public engagement … to get people coming through and generate a buzz around a place as well to spur the wider heritage-led regeneration.”

Tin Win said he was pleased that the renovation would take into account the building’s past as a focal point for tourism.

“If [Turquoise Mountain] can do it, it will be very useful for the country,” he said. “The building should be renovated; it is still useful and is right in the heart of the city – all of the tourists go to that area.”

A history

Built around 1905, 77-91 Sule Pagoda Road was designed and built for an Indian Merchant by Mr Thomas Swales. It was originally known as the Fytche Square Building, taking its name from the park across the road (now known as Mahabandoola Park).

Swales, who was just in his 20s at the time, left a significant mark on colonial Yangon; in the first decade of the 20th century, he designed the Sofaer building, the British embassy and an extension to St Paul’s School in Botahtaung, among other landmarks sites still standing today. The Fytche Square Building, with its neo-classical façade, was one of his finest works.

Prior to becoming the home of Tourist Burma, the building had an important commercial and cultural role. A wealthy local businessman, U Ba Nyunt, took up the lease and opened the Myanma Aswe, or Burmese Favourite, department store and competed with the foreign-owned stores like Rowe & Co (now the AYA Bank head office) and Whiteaway and Laidlaw.

dsc_6950.jpg

Steve Tickner / Frontier

Myanma Aswe also used the building for its pioneering film company, A1 Film, and it was also home to the office of influential magazine Dagon. Established in 1920, it would nurture a generation of writers, including Dagon Taryar, who was so associated with the magazine that he took his penname from its title.

The building was nationalised by General Ne Win’s government in the 1970s and given to the Ministry of Trade. At that time the Hotels and Tourism Corporation was under the trade ministry, so it became the Tourist Burma headquarters.

The building was one of four heritage sites put up for tender by the Myanmar Investment Commission in July 2012. The commission invited expressions of interest from local or foreign companies interested in turning the site into a hotel. No satisfactory offers were received, however, so the hotel plan never materialised and the building remained under state control.