By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

MAUNGDAW — Administrators in northern Rakhine State say it would be “impossible” for the government to agree to Rohingya refugees’ citizenship demands, in a further sign that Rohingya repatriation is likely to proceed slowly – if at all.

Repatriation of up to 2,200 verified refugees from Bangladesh was supposed to get underway on November 15 under a bilateral agreement reached in late October.

The Myanmar government agreed to accept up to 150 refugees per day but none of those verified has returned to Myanmar and Bangladesh has so far opted against forcing them back.

The United Nations and other international groups have warned that conditions in northern Rakhine are not conducive for the safe return of up to 720,000 refugees in Bangladesh, most of whom are Muslim Rohingya.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

All refugees returning to Myanmar via the Taungpyo Let Wei repatriation centre will be assigned a number. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)

Rohingya community leaders have said refugees would only return if the Myanmar government restores their “full citizenship rights”.

“The promises made by consecutive Myanmar governments concerning the reinstatement of full citizenship have never been implemented,” the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace & Human Rights said in an October 31 statement.

But Maungdaw District administrator U Soe Aung said on November 16 that refugees’ demands were not in line with the 1982 Citizenship Law.

“The things they are asking for, they are impossible,” he told Frontier at his office in Maungdaw town. “If they are asking for citizenship to be given to all of them, there’s no way it will be possible.”

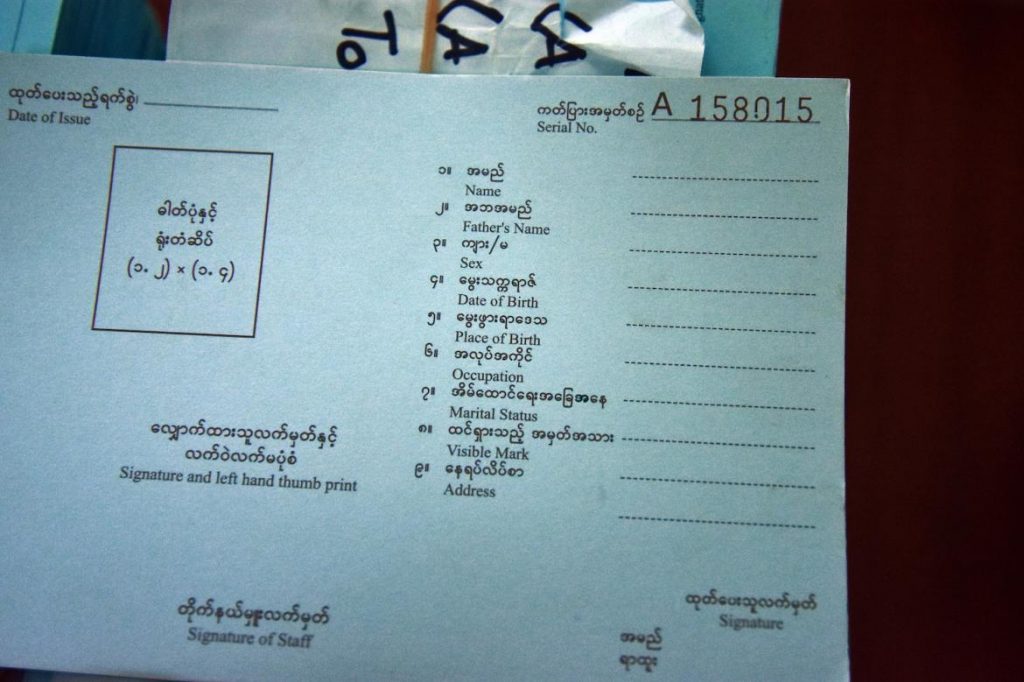

Those who do return will instead be forced to enroll in the government’s National Verification Card scheme, through which their application for citizenship will be considered.

Maungdaw District deputy administrator U Ye Htut. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)

Officials told Frontier, which was visiting northern Rakhine on a government-arranged trip with journalists from 11 other local media groups, that the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population would review applications for citizenship.

U Thant Zin, the deputy director of the Immigration Department for Maungdaw District, said it was impossible to say how long it would take to make a decision on citizenship applications.

Speaking at a refugee repatriation centre established in Taungpyo Let Wei, next to the Bangladesh border, Thant Zin said the process would “take some time … it’s not an easy task that can be done right away because it is concerned with national security”.

Deputy director of the Immigration Department for Maungdaw District U Thant Zin at the Taungpyo Let Wei refugee repatriation centre. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)

At the area known as “No Man’s Land”– a small patch of land that is technically Myanmar territory, but outside its border fence, and where around 5,000 people have sought refugee since August 2017 – a Rohingya community leader said they wouldn’t accept the NVC programme.

Dil Mohammed, 52, said that under the NVC scheme they would be considered foreigners. “We are citizens of Myanmar – our mother, father, and many generations of our ancestors are citizens of the country,” he said.

But he suggested there was some room for negotiation on citizenship, saying that even if the government fulfilled only “one to five percent” of their demands they would come back. “So far though they haven’t even met one percent … they are not sincere.”

“We need basic rights and protection including our citizenship,” he said.

But Maungdaw District deputy administrator U Ye Htut said the authorities in northern Rakhine would continue to wait for refugees to return unless they received other orders from Nay Pyi Taw.

“Although no one has come back, we are ready and will keep waiting,” he said.

Rohingya stranded in the de facto No Man’s Land between Myanmar and Bangladesh. (Su Myat Mon | Frontier)