With the growing strength of the Arakan Army, Rakhine is descending into a conflict zone all too familiar throughout the rest of the country.

By DAVID I STEINBERG | FRONTIER

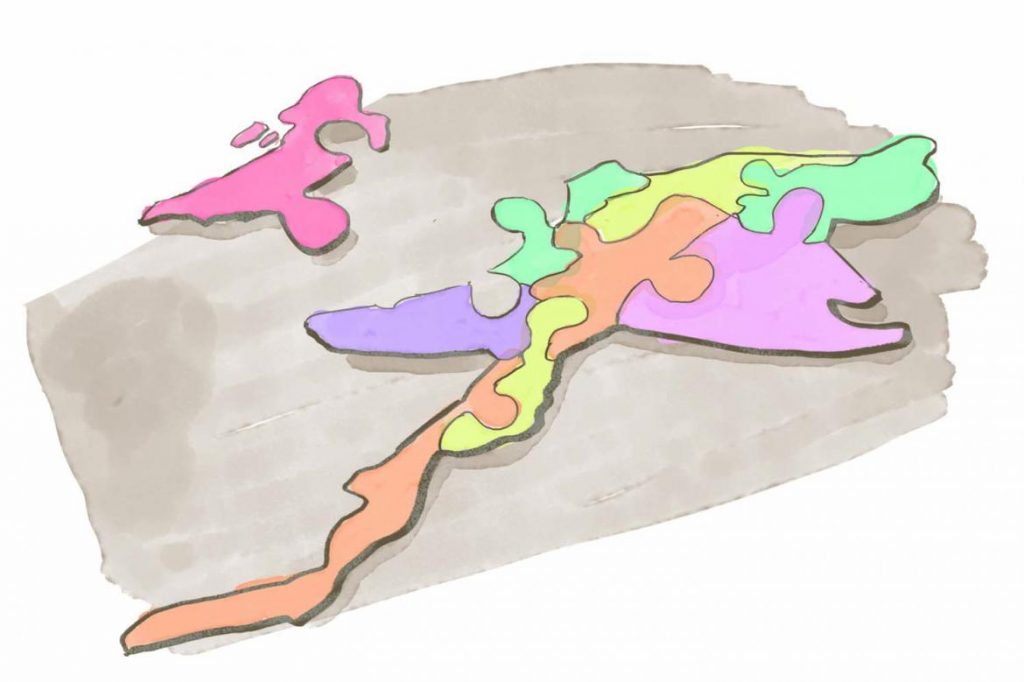

Myanmar is a puzzle – not just for foreigners, but even for many Myanmar people. Like a jigsaw puzzle, it is made up of many different components that can only be fit together with a deft touch. On independence in 1948 it had been delicately pieced into an attractive mosaic with a Bamar core, taking up two thirds, and an ethnically diverse periphery. Over the years we have witnessed ethnic minority attempts to gradually dismantle the peripheral pieces through force of arms. The centre has violently resisted this attempted dismemberment, as it sees it.

Is the last such ethnic piece, that of the Rakhine, now in danger of becoming detached from the Bamar centre? What is happening, why now and what might it mean?

Myanmar has experienced some of the world’s worst and most pervasive ethnic discontent. This has ranged from rebellions against the highly centralised state, threats of secession, and cries for autonomy, federalism or “confederation”, to hopes for removal of the glass ceilings that have held minorities from national positions of power and authority.

Despite some long-lasting ceasefires, almost every one of the major ethnic minority groups have, at least in part, opposed the majority Bamar central government through military means. The Shan, Kachin, Chin, Karen, Kayah, Mon, Wa, Pa-O and Palaung groups – Buddhist, Christian and animist – have all fought for some form of self-rule. Today, ethnic armed groups may possess as many as 50,000 troops. Although these groups may not be a threat to regime survival, active conflict remains a major impediment to national growth.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Rakhine State was for so long the exception. Although it has a long history of minor and ineffective Muslim and Buddhist rebellions, some dating to before independence in 1948, none have seriously challenged the Tatmadaw. For some time there has been public evidence of considerable dissatisfaction with the central government – seen, for example, in the results of the 2015 election – but this was largely ignored. Denied power for so long, the Rakhine have now been added to the list of minority groups waging armed struggle.

When international attention has focused on Rakhine State, it has usually been because of the plight of the Muslim Rohingya minority, over 700,000 of whom fled the Tatmadaw into Bangladesh in 2017-18. But the rise of the Arakan Army in Rakhine State, its increasing strength, and the growing popular acceptance of its military role by the Buddhist Rakhine majority, should also be an issue of intense national and international concern.

Rakhine is one of only two outlying areas in modern Myanmar that were historically separate states, as contrasted with previous tribal amalgams with local rulers and varying degrees of autonomy (the other is Kayah State, whose area covers what were once the Karenni States, which were internationally recognised as independent in 1875 but later quietly absorbed into the Union). The Rakhine kingdom, historically called Arakan, was invaded and subjugated by the Bamar kingdom in 1784-85. After the war, the famous “Mahamuni” Buddhist image was looted from Arakan and resides in splendour in Mandalay, the seat of Bamar culture. Since that time, along with other minorities, the Rakhine have been second-class citizens.

This history still resonates. When some 5,000 Rakhine celebrated the 223rd anniversary of the fall of their kingdom on the site of its former capital in Mrauk-U in January 2018, violence erupted and nine civilians were reported killed and 19 injured. A further 20 police were also injured. The state tends to looks askance at such expressions of historic nostalgia and ethnic nationalism unless it controls the agenda.

Like almost all ethnic armed groups, the Arakan Army is calling for a more autonomous relationship within the Union rather than independence. It seeks a “confederation” along the lines advocated and effectively realised (even if officially denied) by the Wa people. Any federal structure would require constitutional change, and that in turn would require the concurrence of the military, which for half a century refused to consider even the use of the term “federalism”. It was only during the administration of President U Thein Sein, around 2013, that the term was accepted. But federalism has never has been defined for Myanmar, either by the government or by the ethnic groups; each has their own view, and many feel that the Tatmadaw is not prepared to make the concessions required for a federal form of government to develop, let alone one that would grant the sort of autonomy demanded by the Arakan Army.

But why is the Arakan Army growing in strength, and why now? There are likely to be no definitive answers, beyond an amalgam of historical pride, the apparent failure of the national peace process to produce meaningful results, the violence of Tatmadaw repression, state and international concentration on Rohingya needs, a general rise in ethno-nationalism among different ethno-religious groups, the failure of earlier liberation forces like the Arakan Liberation Party, and the training provided by the Kachin Independence Organisation to the Arakan Army.

The political process has seemingly failed as well. Although in 2015 the Arakan National Party won more seats in Rakhine than any other party, it was excluded from sharing power in the state government, which is controlled by the National League for Democracy because the constitution permits the president to nominate the chief minister of each state and region, who then nominates his or her own cabinet. The state legislature has few grounds on which to object to these nominations. The Arakan Army has called for “Way of Rakhita” in 2020 when they hope to have local authority. The year 2020 with its elections seem pivotal in their view.

A former senior general once estimated that ethnic and political bloodshed has cost a million lives since independence from the British in 1948. State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi recognises the importance of halting the violence, and has called the “peace process” – solving Myanmar’s minority issues – her highest priority. But her approach, which entails balancing her party’s goals within the confines set by the military, has not been effective. Many minorities now regard her as having abandoned their needs.

With the growing strength of the Arakan Army, Rakhine is descending into a conflict zone all too familiar throughout the rest of the country. If this final piece of the ethnic jigsaw puzzle becomes emotionally detached from the Myanmar core, it is not only the Rakhine who will suffer but the country as a whole.

The failure of the state to deal effectively with minority discontent has been evident since independence, but the Tatmadaw has exacerbated the problem. Intensifying unrest and increased public support for the Arakan Army indicate that the ubiquitous intelligence services in Myanmar have either failed to anticipate the looming problems, or that the hierarchy ignored the warnings.

Increased Tatmadaw repression will only spur heightened and more broadly accepted demands for greater Rakhine autonomy, and thus likely further exacerbate tensions and violence. The unity of the state of Myanmar is widely recognised, both internally and internationally, as important and desirable, but the rise of ethno-nationalism amongst the Bamar and minorities, and the insensitivity of the leadership – military and civilian – has made conciliation and compromise much more difficult. Near prospects for peace in Myanmar are thus illusory, the danger of further violence all too evident, and the further disintegration of any semblance of national unity a distinct probability.